|

GLACIER

Final Master Plan May 1977 |

|

A PLAN FOR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND VISITOR USE

While Glacier National Park has abundant and varied flora and fauna, it is remarkable chiefly for its picturesque peaks, its glaciers, its bold, massive mountain ranges, its gigantic, glacier-scarred precipices, and its charming lakes cradled in deep, glacier-formed valleys. It offers grandeur and solitude where the visitor may find temporary escape from the tempo of modern life.

The primary objective of the master plan is to maintain this esthetic, pristine experience and to preserve the resource that makes it possible. At present the park is regarded fundamentally as a wilderness resource — one that can be enjoyed at many levels. Depending upon his desire, his capabilities, and the time available, the visitor may stay two or more days within the wilderness area, may experience outstanding examples of this area through short hikes, or if his time is short, may view much of this scenic, pristine world from his car or a boat. Thus, this entire park is utilized by people of varied interests. The master plan proposes to continue this basic use pattern.

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

To guarantee the continuation of the park environment in an unspoiled condition becomes the predominant purpose of the resource management plan.

Because of its isolation and harsh climate, the park largely escaped the initial thrust of the consumptive era that so significantly changed the character of our landscape. Furthermore, interest in establishing Glacier as a national park gained momentum during the first decades of this century, shielding the area from spoliation. Consequently, the resources in Glacier are still largely controlled by environmentally imposed factors. Even with this fortuitous set of circumstances, important elements of the primeval ecosystem are now endangered or completely gone. Most conspicuous of these species are the missing bison and the endangered wolf.

Aquatic ecosystems have been extensively altered by introduction of exotic fishes, including kokanee salmon, grayling, and brook trout. Accordingly, natural systems such as those of the Logging and Quartz drainages require special consideration in developing aquatic management plans. Management of altered systems should stress the protection and/or restoration of natural conditions with an emphasis on native fish populations. Fishing is considered appropriate when consistent with the maintenance of natural population conditions and where not in conflict with natural ecosystem relationships. Artificial stocking of fish may be permitted to restore native fish populations, but not to provide a recreational resource.

Park vegetation has developed naturally under the influence of fire. Much of the present forest cover represents some stage of recovery from past fire disturbance; and probably only a small percentage represents a climax condition. As a consequence of fire-control activity, after establishment of the park, middle-aged seral communities have become more abundant, and the natural dynamics of park ecosystems have been distorted. There is a need for continued study and research in local fire ecology. Development of some biotic communities is known to depend largely upon periodic fires; accordingly, there is a need to develop a management plan that will reestablish the role of natural fire in the environment without hazard to life or property and without destruction of those unique ecosystems that could be destroyed by fire.

With the increase in visitation and the resulting concentration of use, the impact of water collection and sewage disposal systems becomes a concern. This is particularly true in alpine regions such as Logan Pass and Granite Park and Sperry Chalets, where soil depth is shallow and plant cover fragile. Particular care will be taken to ensure that any future utility services do not alter or mar the landscape. The overhead power and telephone lines in the St. Mary, Many Glacier, Cut Bank, and Two Medicine areas should be placed underground to avoid visual intrusion.

The park's lakeshores and streambanks are fragile resources in that they are the focus of visitor use and thus tend to be overdeveloped. A review of existing facilities bordering lakeshores and streams will be undertaken, and a plan developed that will identify intrusions that are not compatible with the primary purpose and use of the area. Moreover, a buffer zone will be provided between the high-water line and any future development.

There is increased concern over resource damage originating outside the park. Most obvious is the fluoride pollution from nearby Columbia Falls and possible degradation of the North Fork of the Flathead River from the Cabin Creek coal fields in British Columbia, Canada. Industrial expansion in the surrounding areas may be expected to alter ecological relationships in the future. Future planning must do more than merely identify the problem; quantitative evaluation will be necessary.

The international boundary between Glacier and Waterton Lakes National Parks has historically been marked by a narrow strip cut through the forest cover. This delineation has recently been accomplished by the use of herbicides. In addition to being a serious threat to fragile resources on both sides of the boundary — particularly to birdlife — it is an unnatural feature intruding into a magnificent resource of international value. Furthermore, it is inconsistent with the tenor of an international peace park, especially where cooperation between the United States and Canada concerning environmental problems is of primary importance. If it is necessary to maintain a boundary swath, other methods should be practiced that are environmentally acceptable. The result will be an international peace park that will, in fact, be a single contiguous ecological unit.

As a natural area, efforts have been made to identify the especially valuable and fragile aspects of the resource. Several areas have been identified as exemplary for their potential contribution to scientific research and for their importance to public understanding as well. They therefore qualify as research natural areas. In Glacier these include sites valued for their geologic, aquatic, or biologic uniqueness. Whatever restraints are deemed necessary by management to preserve these areas will be implemented.

UNESCO's International Coordinating Council for the program on man and the biosphere recently designated Glacier National Park as a biosphere reserve. The objectives of this designation are to provide, "coordinated international research activities," that "specific locations be identified for performing studies... conducted of living, changing plant and animal systems, how they relate to each other, and how man's activities offset and are affected by them... Furthermore, "to assure that genetic material they represent will not be lost..., to use them as locations for monitoring trends and conditions in the terrestrial environment."

Since the major part of the park is roadless, a study of the potential wilderness has been completed in accordance with legislative requirements and with the basic concepts discussed in this master plan. The wilderness proposal was submitted to Congress by the President on June 13, 1974. The proposal recommended 927,550 acres for wilderness with an additional 3,360 acres identified as potential wilderness, which would become wilderness when their nonconforming uses were eliminated. Park management policies carried out by the Canadian government are similar to those of the United States, including a classification of land very similar to our wilderness classification.

VISITOR USE

Persons visiting a major natural park such as the Waterton-Glacier complex can generally be divided into three groups. The first, and by far the largest, spends one or more days in the park following the main, well-traveled routes to attractions such as Logan Pass, Many Glacier, and Lake McDonald. This group of people may also hike short distances on the nature trails and take advantage of a boat tour, but their overall goal lies in seeing the park's resources from convenient, formally developed areas and viewpoints. The second group leaves the main routes to reach the more secluded wilderness threshold areas, where the scale of development is more intimate and where they can experience closer contact with nature. They may hike short distances as well. The third, and smallest, group is characterized by the wilderness user who will spend two or more days hiking, horseback riding, and camping in the wilderness.

The concept of use and development for Glacier seeks to provide opportunities for recreation for each of these groups in a manner appropriate to the resource and to the basic philosophy of maintaining a pleasant wilderness atmosphere. Particular care must be taken, however, to minimize intrusions into the park's sensitive resource areas, such as prime grizzly bear habitat.

Basic to these park experiences is interpretation. Here the goals are to arouse the visitor's interest and intensify his enjoyment of the many resource elements. In order to attain these goals, the program must be flexible and capable of responding to new interpretive opportunities and changing needs. The park is its own museum and interpretation must be accomplished throughout, with the purpose of developing an appreciation and sensitivity for park resources even though this interpretation may occur in a formal structure.

At the major entrances, the visitor will be welcomed and given the opportunity to quickly find what is available to him, the various levels of involvement he may attain, and in what activities he may participate to further enhance his experience. The entrances, however, are not considered the appropriate places for large central museums that detail the many facets of the park's story. Instead, the elements of the Glacier interpretive program will be presented in small sections on site, wherever possible. The extent of facilities will be kept to the minimum to enable the visitor to better see and understand the resource values. They will be located so as to provide introductions to the park's varied levels of activity, including the brief roadside experience, the short walk, the boat ride up a glacial lake, or the overnight hike. Also, information relating to visitor and resource protection will be readily available. Most important, interpretation should encourage the visitor to leave his car and take advantage of the other opportunities available for enjoying the park. The interpretive aids — whether trails, waysides, or shelters — will utilize different presentation techniques to avoid repetition. Explanations must be brief and understandable; the major emphasis will be encouraging the visitor to have his own encounter with nature.

The success of this interpretive program will depend upon a wide variety of publications, personal services, and a relevance to the needs of management, visitors, and resources.

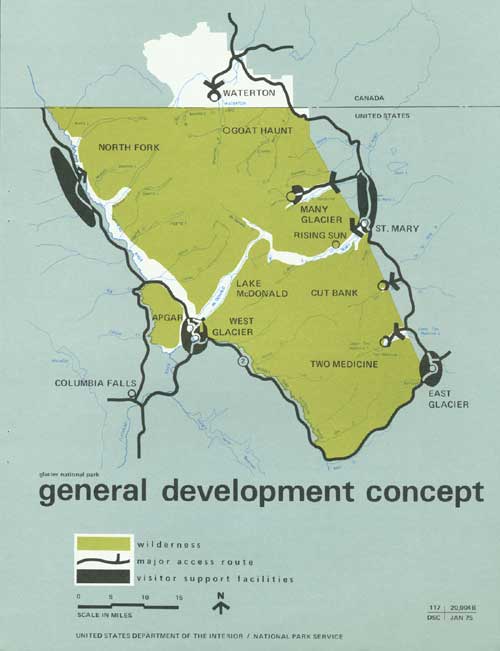

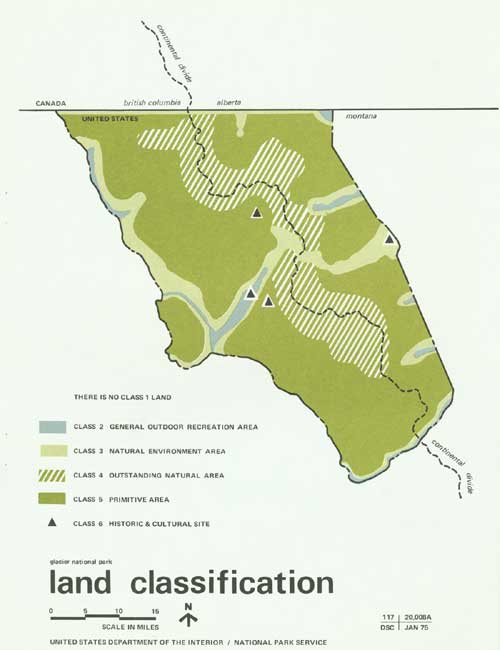

All facilities will be in keeping with the basic concept of the park's purpose and uses. As a result, the general development concept for the park and its immediate environs falls within a framework consisting of three zones or areas. These generally correspond to the land classification plan included in this report.

Two components, Class IV, Outstanding Natural Areas, and Class V, Primitive Areas, comprise the central core of the park. The park resources combine here in lakes, glaciers, and alpine grandeur, and, collectively, this magnificent array is considered the highpoint for the park visitor. All facilities must conform to one predominant function: to assist the visitor in his comprehension and enjoyment of this great natural spectacle.

A division takes place within this core area, stemming from the manner in which the resource is enjoyed. The wilderness will be used directly by both the day-use visitor and the smaller group that remains one or more nights. The park concessioner provides 654 rooms and units in the park. The park provides approximately 1,200 camping sites at auto campgrounds and 263 wilderness overnight campsites. Three privately owned facilities in the park provide 68 units and cabins for Glacier's visitors. Adjacent to the wilderness are semi-wilderness zones that are accessible by road or other mechanized transit. Activities will vary from a brief encounter with the resource, perhaps two hours or less, to a fuller exploration of the park, lasting several days.

As noted on the accompanying map, visitor use will be concentrated in specific areas: Many Glacier, Lake McDonald, Rising Sun, parts of the North Fork country, Goathaunt (at the south end of Waterton Lake), and Two Medicine. Here the required development necessarily places these lands in either a Class III category, Natural Environment Areas; or, in limited cases, a Class II category, General Outdoor Recreation Areas.

|

| GENERAL DEVELOPMENT CONCEPT. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Surrounding the park's core is the third component, a band of access roads, parking areas, and visitor support facilities including restaurants, campgrounds, hotels, and other services necessary for the visitor, but not directly associated with the park experience. In some instances, as at Many Glacier, these support facilities lie within the park and directly abut the core areas. These lands are categorized mainly as Class II, General Outdoor Recreation Areas.

Appropriate lodging and facilities are now and will continue to be provided outside the park in locations convenient to destination points within the boundary. As visitation increases, these exterior developments will probably be expanded. Continued liaison between the National Park Service and the surrounding communities, as well as cooperative planning, can ensure appropriately located visitor facilities.

With the general concept of park use as a basis, the resource's capacity to accommodate visitors must be carefully analyzed. The eventual result will determine the total capacity for the entire park — the optimum number of visitors who can enjoy the park without damage to the resources and without diminishing the quality of their experience. This analysis and the resulting capacity figure must be part of a continuing program. As additional data on the resources are obtained, the entire park complex will be monitored to determine the effect of use and whether or not a change in capacity (either up or down) is necessary.

Within the context of this general concept of use and carrying capacity, each major development or region within the park serves a specific function unique unto itself, but part of the total master plan entity.

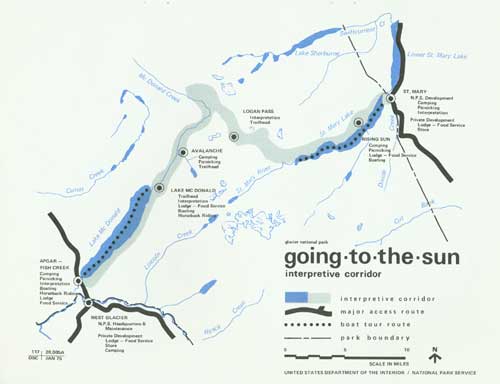

Going-to-the-Sun Interpretive Corridor

This is the general route of the existing Going-to-the-Sun Road, which will continue to be the main attraction for most visitors. Its purpose is twofold: to offer a cross section of the park features for the enjoyment of day-use visitors and to provide a threshold for wilderness use, both for short walks and extended trips. To comply with the stated requirements of the general development concept, facilities must be confined to those necessary for appreciation of the resources.

|

| GOING-TO-THE-SUN INTERPRETIVE CORRIDOR. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Development space is limited and the environment fragile, especially in the higher elevations. Furthermore, the outstanding quality of the resource itself, as well as the potential experience it will provide for the visitor, suggests a departure from the present road access. The goal is to provide for an optimum number of visitors and also to effect an improvement in the quality of the experience now available in this area. The existing road has a limited capacity; is difficult and expensive to maintain; and for the driver of a car, as well as some of the passengers, travel over some portions of the road can at best be described as unsettling.

Thus, it is proposed that a public transit system ultimately serve the Going-to-the-Sun interpretive corridor. The specific vehicle to be used for this transit system will be determined by a special study that will analyze the requirements and recommend a feasible solution. This study will also take into consideration the problems of noise and air pollution, as well as the interpretive potential and the overall esthetic atmosphere. Tourboats on St. Mary Lake and Lake McDonald will become a particularly important part of this system because they will provide an additional means of access to many points around the lakes, and will add greater variety to the activities the visitor may enjoy.

Parking facilities will be provided at suitable locations. Particular consideration must be given in the transit study to concession facilities and campgrounds within the corridor — that is, what method of access (private car or special transit) shall be provided.

Overnight facilities can be provided at lower elevations, but must remain on a scale intimately associated with the surrounding landscape. Ultimately, these facilities might be served by the transit system. A system of bicycle trails should be constructed to complement the proposed transit system.

The St. Mary and West Glacier developments lie at either end of the Going-to-the-Sun interpretive corridor. They each serve several purposes. As the two major park gateways, they introduce the visitor to the park. A variety of services — camping, picnicking, overnight lodge, stores, and food — will be available at both locations. Although it is anticipated that camping will continue on park lands, most other facilities could be provided either within the park or on adjacent lands.

Logan Pass, approximately in the center of the corridor, will continue to be a destination for visitors. Here many elements of the resource are in view, and the alpine atmosphere may be experienced at close range. The dual problem of resource preservation and visitor use is particularly acute in this fragile environment. Moreover, interpretive concepts will encourage the visitor to leave his car and enjoy the rocks, plants, and animals at close range — an especially significant opportunity for the urban-oriented visitor. A wooden walkway has been constructed on a portion of the Hidden Lake Trail at Logan Pass on an experimental basis to protect the fragile alpine meadow.

The Rising Sun area on the east side and Lake McDonald on the west side will continue to provide overnight lodge facilities, campgrounds, picnic grounds, camp stores, and food service. Private enterprise outside the park and adjacent to these areas will supplement these visitor service facilities, as appropriate.

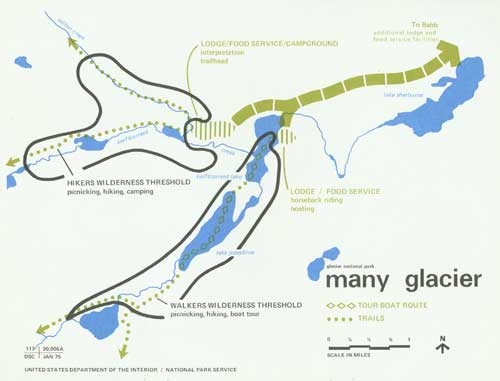

Many Glacier

In this splendid setting there is an extraordinary opportunity for a combination of uses. The area offers some of the most spectacular views in the park, and within a short walk or boat ride the visitor can find himself in the midst of wilderness lakes, forests, waterfalls, and timberline ridges — some of the finest scenery Glacier has to offer. Moreover, Many Glacier is the hub of the park's wilderness trails, and most extended hiking or riding trips begin or end here.

|

| MANY GLACIER. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Even with this excellent potential, some problems exist: space is limited, there is considerable wind on many days, and the plant cover is fragile because of short summer seasons. Many Glacier Valley is the principal lambing area for bighorn sheep; therefore, use in this area must be properly controlled.

Following the existing use pattern, the Many Glacier development, composed of lodges, food service, campgrounds, and interpretive facilities is a core area from which the visitor may enjoy the park. With the exception of interpretive/visitor contact facilities, the development provides an adequate service. Thus, while facilities may be upgraded or replaced, their type, amount, and general location will remain the same. And hopefully, any demand for increased visitor services can be provided outside the park. This will be particularly appropriate if the Blackfeet Indians construct new facilities on the lands in the Babb/Lower St. Mary Lake area. Cooperation between the tribe and the Service on this venture will result in distinct advantages for both.

The basin formed by Swiftcurrent Lake, Lake Josephine, and Grinnell Lake is an outstanding wilderness threshold. Walks, in combination with boat tours, lead the visitor immediately into the wilderness. This pattern is proposed to continue.

Swiftcurrent Creek basin offers the hiker more of a wilderness challenge. Although it is available to those who wish a short walk, it is mainly an introduction to the great wilderness region to the north and west. No boats will assist the visitor, and his contact here will be more in terms of the resource itself.

Surrounding the entire complex is the wilderness, to be enjoyed on many levels — from the visitor relaxing on the hotel terrace to the hiker standing on a high pass or mountaintop.

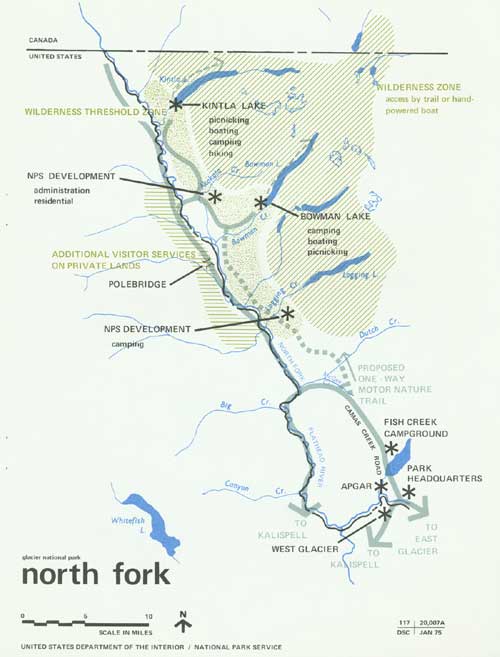

The North Fork

This large portion of the park has received only light use, mainly because of low-standard access roads.

It is proposed that management and development of the North Fork country be geared to that group of visitors who leave the main-traveled routes for the wilderness areas. The emphasis will be placed upon preserving an intimate relationship with the resource — perhaps epitomizing here this master plan's most pervading concept — the serene wilderness experience.

|

| NORTH FORK. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The destination for most visitors will continue to be the Bowman and Kintla Lakes vicinity, more specifically, the outlet areas of each lake. The existing campground at Kintla Lake will be relocated some distance away from its present location on the lakeshore. The main access to Bowman Lake and Kintla Lake will continue to follow the existing narrow, winding, dirt road.

The campgrounds, ranger stations, and related facilities will remain at approximately the same level of development. The main bodies of both lakes have been proposed for wilderness classification.

The Polebridge Ranger Station should continue to be utilized as the principal administrative headquarters for the North Fork area.

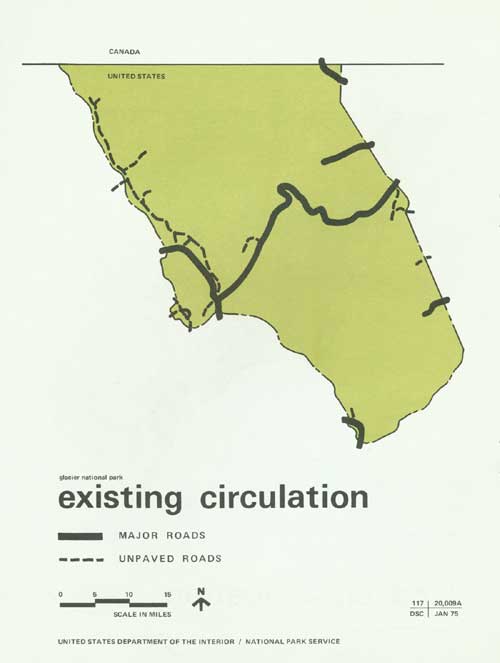

The present North Fork road will remain open for visitor use. From Fish Creek to the vicinity of McGee Creek, however, the existing road may be abandoned. From here, an existing spur road would be improved to form a connection with the Camas Creek road. The section of the North Fork road from McGee Creek to the vicinity of Bowman Creek would then be retained as a one-way motor nature trail.

Waterton Lake

The major portion of this lake lies in Canada within Waterton Lakes National Park. The community of Waterton offers a wide range of visitor services, from hotels and restaurants to gift shops, boat rentals, and gas stations. That part of Waterton Lake that lies within Glacier National Park is an excellent wilderness threshold for visitors arriving on tourboats or privately owned craft from Waterton Townsite. Goathaunt, at the southern terminus of the lake, is an excellent springboard to wilderness travel.

Two Medicine

Oriented to the lake, the purpose of this development is similar to that of Many Glacier, but on a smaller scale. At present, camping, picnicking, boating, and food service are available and will continue. Two Medicine is an excellent area for viewing the southern half of the park's wilderness. The boat tours provide the opportunity to see a sample of the park's prime resources, and at the upper terminus there are opportunities for short walks. Overnight lodge facilities are available nearby at East Glacier Park, and any needed expansion can be accommodated in this vicinity or at lower Two Medicine.

Peripheral Development

From the park's circumferential road system several minor vehicular accesses, mainly trailheads associated with small campgrounds and picnic areas, lead to the park.

U.S. Highway 2 passes through a small portion of the park that contains a mineral lick for mountain goats. This important part of the mountain goat environment will require special attention if U.S. 2 is relocated, to ensure that the area is accessible to the animals. It can also be a significant interpretive feature.

The Wilderness

The park's wilderness may be enjoyed from appropriate viewpoints along the Going-to-the-Sun Road and peripheral roads or from trails. The concept underlying the master plan's proposals for this large section of the park emphasizes the continuation of the ecological processes that created these unique natural features, and allows only that level and type of use that the resource can tolerate without deterioration. While visitor use will continue to be encouraged, appropriate management restraints will be initiated to ensure the protection of the wilderness' natural resources.

Although it is desirable to retain large park areas uninterrupted by developments, certain parts of the wilderness can be designated and managed for a specific level of use. Granite Park and Sperry Chalets allow the wilderness traveler to experience Glacier's wild lands without the usual specialized knowledge or encumbering equipment. It is proposed that this type of use be continued.

Winter Use

Glacier's visitation declines markedly during the winter months when heavy snow blankets the entire park. Some of the magnificent winter scenery can be enjoyed through winter-use activities.

In response to Executive Order 11644 an environmental impact statement was prepared and public meetings held November, 1974 on the establishment of snowmobile routes. As a result of that process snowmobile routes were not established and previous use was discontinued.

Cross-country skiing and snowshoeing are permitted, and are increasing in popularity. In the past these activities have been considered appropriate anywhere in the park other than avalanche areas; however, recent studies in Minnesota and Wisconsin indicate they can adversely affect wildlife under the stress of winter. Additional research on these effects is required, as is an environmental assessment to determine whether some activities should be restricted in some park wildlife habitats. Should skiing, and snowshoeing activities continue, plans will have to be devised to resolve their incompatibilities.

ADMINISTRATION

Facilities needed for administration of the park include offices, residences, maintenance areas, and accompanying utility systems. These are now located away from the major resources in peripheral sites and at sites outside the park. The plan proposes no change in this pattern. The headquarters at West Glacier will continue to be maintained, as well as district and subdistrict facilities in or near major developed areas on both east and west sides of the park.

LAND CLASSIFICATION

The recommended programs for management and use of the irreplaceable natural values of Glacier-Waterton Lakes International Peace Park are coordinated with the park lands use concept described by the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission in its land classification system. The accompanying map classifies all park lands in accordance with this system and with the master plan proposals in this document. If implemented, these will set a pattern for future management, and ensure the park's continuance as an unspoiled example of the great natural heritage of both the United States and Canada.

|

| LAND CLASSIFICATION. (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| EXISTING CIRCULATION. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

glac/final_master_plan/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jul-2010