Historical Background

| November 6-23 1805 |

"Ocian in View! O! The Joy"

Near Pillar Rock, on November 7 Clark, seldom emotional in his journal, exclaimed, "Great joy in camp we are in view of the Ocian . . . this great Pacific Octean which we been so long anxious to See." But he was mistaken. He was actually viewing the open-horizoned estuary of the Columbia, whose salty waters reached up some 20 miles from its mouth. [122]

Just the day before, a violent storm had erupted. Rain persisted for 11 straight days, never ceasing for longer than 2 hours. Lightning flashes seared the sky, and thunder boomed like cannon. Day and night, everyone was soaked and miserable, as well as weary from bailing water out of the boats and wringing out wet clothing, bedding, and equipment. Sacagawea and some of the men became seasick as high waves and heavy winds tossed the boats about like driftwood. Only extreme exertion prevented huge waterborne cedar, fir, and spruce trees—bigger than anyone had ever seen, some almost 200 feet long and up to 7 feet in diameter—from crushing the canoes. Hunting was impossible, but dried fish, roots, and dogs were sometimes purchased from Chinook Indians, who were encountered almost daily. Finding shelter was difficult. Fires were hard to start and maintain.

|

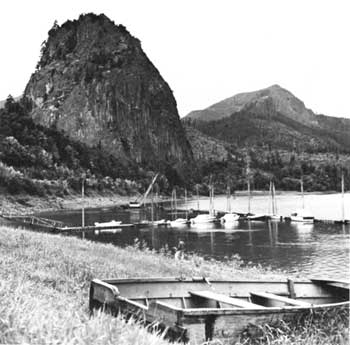

| Beacon Rock, a lava monolith about 900 feet high on the Washington side of the Columbia today included in a State park, is one of the landmarks mentioned in the Lewis and Clark journals. (Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (Blair, 1964).) |

Through it all, the boats inched their way along the northern side of the estuary. On November 10, when they tried to round Point Ellice, opposite present Astoria, Oreg., giant waves whipped them back. Camp had to be established along the point's more protected eastern side on a pile of drift logs. During the night, the logs were awash in the tide for awhile. Small stones from the steep nearby hillside, loosened by the driving rain, pelted the party. The next day, to prevent waves and floating tree trunks from further damaging or destroying the canoes, they were sunk with rocks. The men then moved inland a short distance to high ground. In the predawn hours of the 12th, a severe thunderstorm broke out, and continued bad weather held the group to the camp until November 15.

In the meantime, 2 days earlier, Lewis and Clark had dispatched Colter, Willard, and Shannon in an Indian canoe, which rode the swells better than the expedition's craft, to explore the shoreline beyond Point Ellice to see if a better campsite could be found. Colter returned the next day with a favorable report. In mid-afternoon, a party of five men carried Lewis, Drouillard, Joseph and Reuben Field, and Frazer around the point in a canoe. They proceeded by land toward the mouth of the Columbia, exploring and looking for the white men the Indians had said were in the area. That day, the Pacific may have been sighted, but it is unlikely because of the stormy conditions and the few hours of daylight available.

|

| Some stretches of the Columbia River are relatively unchanged since 1804-6. This photograph was taken from Sam Hill Viewpoint, about 25 miles east of Portland. Vista House, atop Crown Hill, middle right, provides another vantage point. Between the hill and the river is water-level freeway I-84. (Oregon State Highway Division.) |

Back at the base camp, abating weather on the morning of November 15, the day after Lewis left, made possible the refloating and reloading of the canoes. But high winds sprang up and delayed departure until 3 o'clock. Clark and his party then moved about 4 miles downstream around Point Ellice to a sandy beach Colter had earlier discovered, about a half-mile southeast of Chinook Point. There they met Shannon and five Chinook Indians. Some distance below, Shannon and Willard had met Lewis, who took the latter with him and sent the former back to await the main body. Camp was made near an abandoned Chinook village, consisting of 36 board houses, whose lumber was used in building shelters. This campsite was utilized as a main base until November 25.

Visible for the first time were Point Adams and Cape Disappointment, the whole breadth of the Columbia's mouth between those headlands, and beyond them the open sea—the glorious Pacific. [123] After many months of privation and danger, the Corps of Discovery had reached its goal!

|

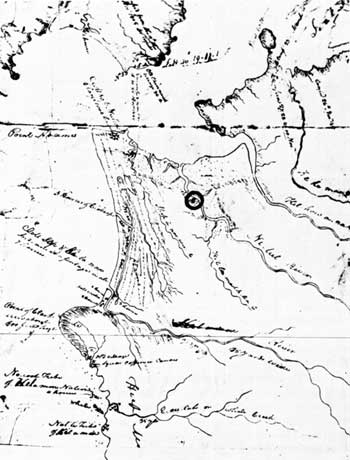

| Central portion of Clark's map of the mouth of the Columbia and adjacent coastal area. A circle has been added to this symbol for Fort Clatsop. (THWAITES, VIII, Map 32, Part III.) |

The next day was clear with high winds. The men relaxed and lolled about, satisfied they were at journey's end. They watched mountainous waves rolling free out in the ocean and seagulls soaring dreamily about overhead. Clark estimated the distance from Camp Wood at 4,133 miles—3,096 from there to Camp Fortunate, then 379 miles overland to Canoe Camp on the Clearwater, followed by a 658-mile river trek to the mouth of the Columbia. On November 17 the Lewis party, which had proceeded to Cape Disappointment and explored the seacoast to its north for a short distance, arrived back at Chinook Point. The next day, Clark and 11 men set out. [124] Between then and the 20th, they traveled overland to Cape Disappointment and explored about 9 miles to its north.

Finding Lewis' name carved on a tree near Cape Disappointment, Clark etched on it his own, "by land," and the day, month, and year (November 18, 1805). Some of the other men carved their names, too. The next day, Clark engraved another tree. On November 23, back at the Chinook Point camp, he, Lewis, and the entire complement engaged in one more tree-carving ceremony.

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/lewisandclark/intro47.htm

Last Updated: 22-Feb-2004