.gif)

MENU

Design Ethic Origins

(1916-1927)

Design Policy & Process

(1916-1927)

![]() Western Field Office

Western Field Office

(1927-1932)

Decade of Expansion

(1933-1942)

State Parks

(1933-1942)

|

Presenting Nature:

The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, 1916-1942 |

|

IV. THE WORK OF THE WESTERN FIELD OFFICE, 1927 TO 1932 (continued)

EXPANDING THE BUILDING PROGRAM (continued)

DESIGNS FOR THE EDUCATIONAL DIVISION

Under the leadership of chief naturalist Ansel F. Hall, the Educational Division grew in the 1920s. This division offered myriad programs to teach visitors about the natural history of the parks, including interpretive trails and waysides, museums, gardens, nature shrines, and amphitheaters. Since many of the division's programs involved building structures or trails, the Landscape Division had worked closely with the division since 1924, when the Yosemite Museum and the Glacier Point Lookout were being planned and constructed in Yosemite.

Herbert Maier, the designer of these buildings, collaborated closely with Hall and a special committee of outside experts to work out the final design of the buildings and their exhibits. Maier went on to design a number of museums funded by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Foundation for various national parks. He created a series of museums for Yellowstone and expanded the idea of the trailside museum devoted to the interpretation of a single aspect or particular area of a park, such as the Norris Geyser Basin or Fishing Bridge area. By 1930, he had also designed the Yavapai Point Observation Building and Museum on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. The government landscape designers, particularly Vint, collaborated with Maier and the museum committee in selecting the sites for the museums and reviewing Maier's designs.

|

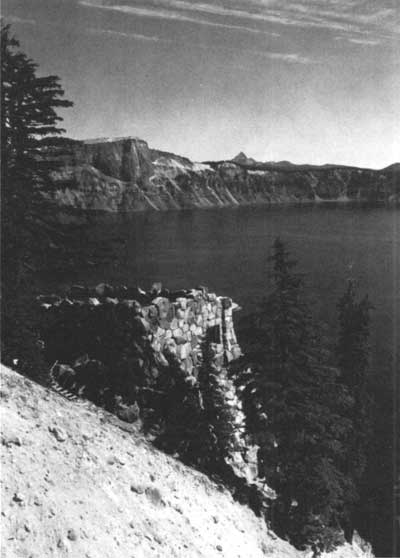

| Sinnott Memorial at Crater Lake was the first museum designed by National Park Service's Landscape Division and funded by Congress. Intended as an observation station and an interpretive center, it was built into the steep slopes below the crater rim. When National Park Service photographer George Grant photographed the building in October 1933, he captured the anthromorphic form of the head of an eagle as depicted in Native American art. Mountain Hemlock and other native specimens were later planted to stabilize and naturalize the steep exposed slopes in the foreground. (National Park Service Historic Photography Collection) |

The first museum to receive special congressional funding was the Sinnott Memorial at Crater Lake. Designed by Vint's office, the building closely followed the solutions for a rimside observation-type building that Maier had worked out for the Yavapai Point Observation Building. It was also influenced by Colter's Lookout and Hermit's Rest at Grand Canyon. Rather than being located at the top of the rim, however, the stonemasonry building fit closely into the steep slope of the crater high above the lake and assumed the form of an eagle's head.

By 1930, the concept of natural history interpretation had expanded to encompass trails, trail hubs, wild flower gardens, trailside nature shrines, branch museums, naturalist residences, and outdoor amphitheaters. The education programs expanded and made use of the natural and scenic features for on-site interpretation. As these structures developed to serve the expanding interpretive programs, they assumed a distinctive stylistic character that placed them in both the traditions of rustic architecture and naturalistic landscape design.

Most ambitious was the education program at Yellowstone, where the Old Faithful Museum was accompanied by branch museums at Fishing Bridge, Madison Junction, Norris Geyser Basin, and Mammoth Hot Springs. The museum concept thus grew from the idea of a central museum with an outlying lookout, as built in Yosemite about 1925, to a parkwide system of branch museums, each containing a museum, residence, amphitheater, trails, parking areas, paths, and comfort stations. They could be connected with a nearby concessionaire's complex and campground to provide visitors convenient access at all times of the day.

Amphitheaters and interpretive waysides were additional structures that emerged from the work of the Educational Division in the late 1920s. In 1927, Ernest Davidson, the resident landscape architect assigned to Yellowstone, discussed various improvements and installations of exhibits at the major overlooks at the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, including Artist's Point and Inspiration Point. Davidson made sketches on site incorporating both Hall's and his own ideas. Although he sent them to Wosky in the San Francisco office to have finished drawings made, there is no evidence that the final drawings were ever made. The collection, however, illustrates the vision the Landscape Division had for developing interpretive viewpoints in the late 1920s. Although Hall's plans for redeveloping the paths and overlooks along the Canyon never materialized, the ideas were further expanded in the master plans of the 1930s and laid the groundwork for future interpretive developments incorporating trails, walkways, observation platforms, and interpretive shelters, called "nature shrines." Although such features were being developed in a number of parks, Yellowstone's interpretive program led the service in integrating these features into the design and operation of museums throughout the park. These structures drew heavily from the traditions of rustic architecture and naturalistic gardening.

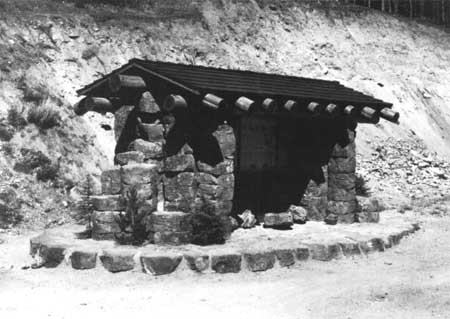

The first interpretive wayside constructed at Yellowstone was the kiosk at Obsidian Cliff (1931), which explained to the public the site's natural formation, a mountain of volcanic glass approximately two miles long. This kiosk was one of several significant innovations made by Carl Russell, the park naturalist. Built on the west side of the Grand Loop Road twelve miles south of Mammoth Hot Springs, the kiosk, measuring six by sixteen feet, was set twenty-five feet from the road at the edge of a parking lot and at the base of the cliff. It was constructed of clustered columns made of basaltic stone blocks and a wood-shingled, overhanging roof supported on log timbers. The open-sided structure housed exhibit panels that were originally placed behind glass. Flagstone paving and native plants surrounded the kiosk in its original design. A number of smaller trailside nature shrines were constructed of native logs and stones in Yellowstone at the same time. Several of these structures were illustrated in the National Park Service's portfolios published in the 1930s. [76]

|

| The Obsidian Cliff Kiosk in Yellowstone National Park was the first nature shrine designed by the National Park Service in the early 1930s to interpret points of interest by providing on-site exhibits. The design illustrated the converging principles of rustic architectural design and landscape naturalization. Photographed just after construction in 1931, the shelter sat upon a flagstone terrace and was planted with several spruces and other plants. The raw, unfinished slopes of the parking lot and road are visible beyond. (National Park Service Historic Photography Collection) |

The amphitheater was first incorporated into the design of Yellowstone's Old Faithful Museum and similarly appeared at the Fishing Bridge Museum. The idea of an amphitheater in a national park, however, was not new. In 1920 at Yosemite, a simple outdoor auditorium seating 250 people had been constructed in a natural amphitheater surrounded by trees using funds provided by the Sierra Club and M. Hail McAllister of San Francisco. The seats were in three rows of twelve-foot pine logs about eighteen inches in diameter with the bark left on. They had backs of canvas inserted over one-inch iron pipe frames and were arranged on a slope facing the speaker's stand. Charles Punchard praised this design as "attractive, unique, and comfortable" and recommended the development of outdoor amphitheaters in other parks. [77]

|

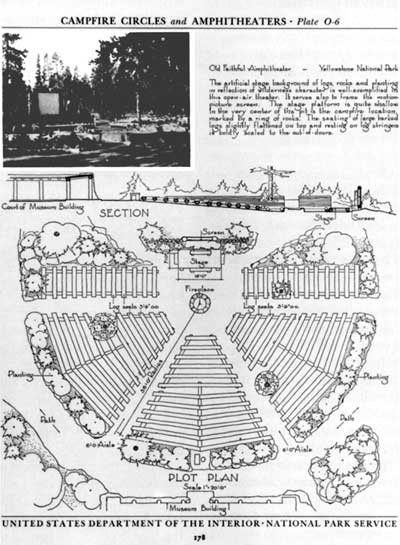

| The amphitheater at Yellowstone's Old Faithful museum was featured in the National Park Service's portfolio Park Structures and Facilities of 1935 as a design ideal for a woodland setting and having a wilderness character. (Park Structures and Facilities) |

Outdoor theaters and amphitheaters appeared across the nation in the early twentieth century; they were a popular feature in parks, college campuses, and private estates. The grandest was the great Greek Theater at the University of California, Berkeley, a prototype with which Maier and Vint were familiar. National park designers likely knew of the amphitheater designed by Myron Hunt at Pomona State College in California. Articles appeared in Landscape Architecture and other journals in the 1920s on the construction of outdoor theaters. Frank Waugh had a continuing interest in amphitheaters and published Outdoor Theaters: Their Design, Construction, and Use of Open-Air Auditoriums in 1917 and several articles in the 1920s. He wrote on natural amphitheaters and the relationship of the amphitheater and the campfire. In his own landscape work, he adapted the more traditional forms to the natural setting of national forests. [78]

The semicircular amphitheaters at the Old Faithful and Fishing Bridge museums in Yellowstone were modified versions of the traditional Greek theater form built into a hillside with radiating aisles and rows of seating rising evenly from a center stage. Maier's semicircular design was better suited to the intimate woodland surroundings and use for evening lectures and slide shows. While he clearly drew from the Berkeley example, he developed it on a much smaller scale and in a naturalistic manner befitting its forested location. Screens of trees hugged the theater's edges and created a backdrop for the stage, and scattered trees within the theater were left in position while seats were built to either side of them. Roughly hewn logs were laid vertically to create a backwall for the stage, echoing the verticality of the surrounding forest and framing the slide screen.

Benches were also fashioned from split logs. The amphitheater incorporated the traditional campfire in the form of a ring placed before the stage. As Maier's amphitheater, with its radiating aisles and arcs of seating descending the slope toward the stage, was adopted in other parks, this campfire circle was moved to one side of the stage, so that smoke from the campfire would not obscure the audience's view of the slides being projected on the screen or activities occurring on stage.

By 1932, the amphitheater had become an important and regular feature of park campgrounds where evening ranger talks could be heard. Most of these were adaptations of Maier's theater in the woods. Variations included outdoor theaters at Zion and Mesa Verde, where the theater was situated in a depression along the rim of a canyon to present a scenic view that could be interpreted by a ranger or simply contemplated in a type of open-air temple.

By the end of 1932, the expansion of the education program was reflected in the design of new kinds of structures and features in the parks. Amphitheaters, nature trails, lookout shelters, nature shrines, and campfires were built in conjunction with campgrounds and other developed areas. Park designers at Paradise experimented with a centralized trail hub from which interpretive trails could lead to scenic areas and special features of the park in conjunction with the new landscape work around the community building and housekeeping cabins. This idea was later recommended for the terminus of trails at Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite. [79]

FORESTRY AND THE PROTECTION OF PARK FORESTS

Another growing function of the National Park Service was the protection of park forests carried out under the Forestry Division headed by fire-control expert John Coffman. Coffman had developed detailed surveys of fire hazards in a number of parks and comprehensive plans for the prevention and suppression of forest fires in those areas. A number of serious fires, including the Half Moon fire at Glacier, called for liaisons and collaborative effort with other agencies. In 1929, the Landscape Division collaborated with Coffman to develop standard designs and specifications for forest lookout towers. [80]

In 1931, the collaboration resulted in two lookouts: the Watchman at Crater Lake and the Shadow Mountain Fire Lookout at Rocky Mountain. A year later, Lassen's Harkness Peak Lookout was added to the repertoire of successful designs. These designs used stone and timber materials fashioned into functional designs that included a large viewing platform entirely surrounded and enclosed by large windows and surrounded by an outside balcony. The fire lookout posed a dilemma for designers: in order to perform their essential function, these structures needed to be situated on prominent peaks; they needed to provide visibility in 360 degrees; and they could not be concealed or screened by vegetation. The use of native stone and timber and the simple, rectangular form with hipped roof contributed greatly to the ability of these structures to blend inconspicuously into their setting, even when viewed from a neighboring peak or nearby trail. Towers such as the Watchman not only helped detect fires in remote areas, but also were open to visitors for the enjoyment of scenic views. These basic designs would be repeated in appropriate local materials in many variations throughout the parks in the 1930s.

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Oct 31, 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/mcclelland/mcclelland4c1.htm

![]()