|

Rocky Mountain National Park A History |

|

|

Chapter 6: PARADISE FOUNDED

THE NEWSPAPER headline blazed: "Naked, Unarmed and Alone, 'Eve' Goes Forth Into Forest." An eye-catching story, complete with photographs, described a twenty-year-old college co-ed from Ann Arbor, Michigan, Miss Agnes Lowe, as she waved good-by to a crowd of well-wishers. She was leaving to spend a week with nature in the wilderness of Rocky Mountain National Park. It was Monday, August 6th, 1917, when Miss Lowe's tale appeared in The Denver Post. This "modern Eve" had donned a suitable "cave woman" costume, resembling an abbreviated leopard's skin, before entering the newly created "Garden of Eden." Enos Mills and Park Supervisor L. Claude Way joined the bevy of reporters, photographers, local dignitaries, and "nearly 2,000 persons" to watch the girl dash into the woods near the base of Longs Peak, supposedly heading into the Thunder Lake country. With farewells completed and photographs taken, rangers restrained the crowd as Miss Lowe began her adventure. Enos Mills had the honor of escorting Miss Lowe, "The Eve of Estes," as far as the beaver ponds on the Roaring Fork. From there, Mills "left her to pursue her barefooted way alone. . . ." [2]

A girl attempting to live alone in the wilderness was hardly a new idea in 1917. Others had recently experimented with the same adventure at several locations in the East. Yet no one would really have classified living "without clothing, food, weapons, or shelter" as a national fad. It was new to Colorado. And it was certainly unusual enough to attract the attention of most readers. Almost at once newspapers across the country started carrying the story, providing their readers with the latest details about "Eve." At the same time that news of the World War captured page one, the Eve of Estes kept reports coming from Rocky Mountain National Park. As she worked her way through a week in the wilderness, tidbits about her progress enchanted the public and drew attention to the new Park. The creation of Rocky Mountain National Park in 1915 meant that many people started to look at these mountains differently. Conservationists such as Enos Mills saw the region as a preserve, a place to be guarded from cattle yet enjoyed by people. Businessmen believed the new Park would enhance the reputation of their area, now starting to prosper from growing numbers of tourists. Most ideas about developing hotels, roads, and recreation as well as publicizing the Park could not be called new in 1915, but with the establishment of a national interest in the area further development was intensified. Work was already under way on the Fall River Road, connecting Estes Park and Grand Lake with a scenic route across the Divide. Like building projects of former years, this road symbolized only the latest effort to draw more visitors into the region. And just like Fall River Road, the newly created Park was seen as another way to promote the area, a way to make the region even more famous as a resort. For years, however, promoting and developing this stretch of the Rockies had been a local effort. Occasionally a few other people within Colorado offered some kind words. Rarely did outsiders take the trouble to promote or advertise the area. Little seemed to change while the region was a national forest. But once Congress created the Park in 1915, a new era of promotion and protection began. Determining how these mountains and the new Park would be promoted, protected, developed, and enjoyed now became a federal task. Forging a national park out of territory already explored and somewhat settled for over fifty years was not easy. Over the next decade and a half, well-meaning people worked hard to decide what direction this new park should take. Between 1915 and 1929, Rocky Mountain National Park became a little like a stage, its magnificent horizon serving as a backdrop, upon which a variety of actors argued about which play should be presented. Upon the scene came familiar local players such as Enos Mills, eager to recite old scripts for new audiences. Soon other characters arrived, upstaging those more familiar. And other scripts also appeared, some sent from places as distant as Washington, D.C. Everyone wanted to please the audience. Once in a while a comedy act came along, like that of the adventuresome Miss Lowe, providing a touch of levity. But from 1915 onward, those people intent on producing a national playground took their roles very seriously.

A new era began on July 1st, 1915 when C. R. Trowbridge arrived in Estes Park and took charge as Acting Supervisor of Rocky Mountain National Park. A New York native and veteran of the Philippine insurrection, Trowbridge also worked with the Secret Service until 1913 when he became a field representative for the secretary of the interior. Based on that experience, he was selected to organize the administration of this new park. During the months that followed, Trowbridge watched work proceeding on the Fall River Road; followed trails to Bear Lake, Lawn Lake, and Bierstadt Lake; and inspected resorts run by Abner Sprague in Bartholf Park, by W. H. Ashton at Lawn Lake, by the Higby brothers at Fern Lake and the Pool, and by E. A. Brown at Bear Lake. He issued numerous permits for guides. He examined timber cutting sites and posted a number of "Fire Warning" signs. He also bought furniture and opened an office in Estes Park on July 10th. From there he directed the efforts of his three rangers, R. T. McCracken, Frank Koenig, and Reed Higby. Paying them each a salary of $900 per year, Trowbridge dispatched these men to patrol the Park, repair old Forest Service ranger stations and telephone lines, and work on the trails. They also fought a forest fire during their first month on the job. Watching the dedication ceremonies must have been an enjoyable task that September, but soon after the whole squad spent "considerable time" searching for a Dr. R. T. Sampson, reportedly lost along the Continental Divide. For Trowbridge and his men there was always plenty to do. During his fifteen months as acting supervisor, C. R. Trowbridge managed the Park with the dual goals of protection and regulated use. Fighting forest fires, patrolling for hunters or trappers, or chasing neighboring cattle out of the Park were acts of protection. Having brush and rubbish cleared from roadsides displayed some common sense regarding aesthetic guardianship. Opening trails and repairing roads merely augmented the work already being done by local guides, packers, horsemen and residents. Issuing permits for guides, resorts, and reservoirs testified to the continuation of practices familiar even before the Park's creation. But some less common activities, no longer identified with today's national parks, also surfaced in 1915 and 1916. Trowbridge issued several timber cutting permits, meaning local people continued hauling lumber from the Park just as if it were still a national forest. Firewood could also be taken, using the dead or down trees at a cost of only fifty cents per cord or less. In fact, with the exception of regulating grazing and hunting, it seemed as if few changes really took effect in the management of these mountains as it evolved from a national forest into a national park. Most people applauded the protective efforts of the rangers, but if they had promptly enforced a list of rigid rules or regulations, immediately restricting common practices in the area, the rangers might have created a furor. In 1915, however, few rigid rules had even been considered, much less written. Even a centralized bureau in Washington offering a uniform administration for all national parks had yet to be created. Only in August of 1916 when Congress organized the National Park Service did a consistent philosophy and uniform policy for the national parks appear. Soon the administration of Rocky Mountain National Park began to reflect the goals mandated by Congress for all the parks: "to conserve the scenery, the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations." [3]

Prior to the development of the National Park Service, management of each park or monument depended upon who was in charge, the whims of Congress, and local pressure. Each of the thirty-one areas set aside by 1915 tended to have its own special set of rules. No clearly stated purpose for all of them existed until Congress formulated the dual goals of preservation and "enjoyment." The national park idea had evolved in a haphazard fashion. Historians offer many reasons for the birth of this unique, wilderness park concept. Some have suggested that a European heritage of hunting reserves kept by the nobility took root in a more democratic American environment. Others link the idea to the town commons established for public use in villages of the East. The beginnings of nationalistic pride during the 1820s and 1830s might also have contributed to an appreciation of the nation's natural wonders. Feeling competitive with an older European culture Americans boasted about the natural grandeur of their country. In the absence of any native literature or art, self-conscious Americans tried to "show up" Europe by extolling the virtues of American geography.

Influential writers such as Thoreau and Emerson helped contribute an intellectual justification for appreciating and protecting objects of nature. They also insured that mere thoughts of conservation would be strongly linked to a sense of aesthetic appreciation. Proposals for parks and preservation soon came from other spokesmen, such as Frederick Law Olmstead, landscape architect and park planner. Olmstead argued for government control of scenic land, claiming the advantage of "protection for all its citizens in the pursuit of happiness." [4] And happiness meant preserving areas that permitted the "contemplation of natural scenes of an impressive character." Once designated as a public park, such an area would bring people "relief from ordinary cares, change of air and change of habits . . . favorable to the health and vigor of their intellect beyond any other conditions which can be offered them." In the view of visionaries such as Olmstead, recreation in such grand natural settings offered metaphysical benefits, something like a spiritual quest, with a "pilgrimage" to a park providing the "means of securing happiness." [5] Preservation and recreation were seen as ideological companions. The images of freedom, adventure, wildness, independence, vigor, rest and play, all helped augment the idea of parks. The audience for such ideas was small but receptive. Other intellectuals agreed with the need for a more sensitive attitude toward nature. That sympathetic attitude became an urgent desire to guard especially scenic spots from being despoiled. Active efforts toward preservation began. In 1864, Congress granted Yosemite Valley and the nearby Mariposa Grove of redwoods to the state of California "for public use, resort, and recreation" [6] and established a precedent for setting aside large tracts of undeveloped land simply in the name of "recreation." In 1872, a massive forested plateau surrounding the headwaters of the Yellowstone River and dotted with unique thermal basins, deep canyons, and jeweled lakes received similar protection. With this two-million-acre reserve—Yellowstone National Park—set aside "as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people," historians mark the official beginning of the American national park movement. During the following decades additional parks joined Yellowstone in its elevated status as a national treasure. Among them were Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant, all created in 1890. Mount Rainier followed in 1899, Crater Lake in 1902, and Glacier in 1910. Along with those large parks sites of historical interest such as the ancient ruins at Mesa Verde received protection through the 1906 Antiquities Act. By 1915, when Rocky Mountain gained its national park designation, thirty-one parks and monuments had been created. As the number of preserves grew, a clear policy for managing them all had to be developed. In some, such as Yellowstone and Yosemite, the U.S. Cavalry worked as guardians; in others, civilians with political influence took charge. Compounding an inconsistent management was a penurious Congress that voted very little money for improvements. Visitors to those early parks sometimes found rules unenforced and vandalism rampant. A wide gap existed between intellectuals who encouraged an appreciation of nature and the average traveler, called "the great unwashed" by an unsympathetic observer. Viewing heaps of litter in Yellowstone, one traveler reported: "Society in general goes to the mountains not to fast but to feast and leaves their glaciers covered with chicken bones and eggshells." [7] Yet national park administrators continued to be idealistic about preserving nature "unimpaired." One could almost understand that an ill-informed public, not displaying aesthetic sensitivity, might bring its rapacious attitudes, destructive tendencies, sloppy manners, and careless attitudes to the parks. Just as it took work to create preserves, similar efforts had to be directed toward educating people to appreciate the parks without destroying them. John Muir served that purpose for Yosemite in particular and the West in general. Enos Mills followed Muir, promoting first forests and conservation and later the ideals of preservation in the Rockies. "Go to the trees and get their good tidings," Mills urged the public, paraphrasing Muir who had paraphrased Emerson. "Have an autumn day in the woods, and beneath the airy arches of limbs and leaves linger in the paths of peace." [8] Dozens of other writers followed that theme, encouraging turn-of-the-century travelers to discover "the healing powers of nature." [9] "Elsewhere man must live by the sweat of his brow," one national park advocate wrote. "Here let him rest and play." [10] By 1915 national parks were becoming the "playgrounds of the people." Exactly how these playgrounds were to be managed or used remained a question.

For years the national parks lacked a cohesive organization or philosophy. They needed direction. Intellectuals saw parks simply as wilderness preserves. Years earlier, Thoreau had observed: "To preserve wild animals implies generally the creation of a forest for them to dwell in or resort to. So it is with man." [11] Parks afforded that physical space offering wildness. At the same time, parks served as a source of nationalistic pride, "crown jewels of the continent." The railroads encouraged Americans to "See America First," especially before spending dollars in Europe. Advertising grand scenery of the parks helped convince people to spend their vacations seeing sights within the nation. Always able to make a case for wilderness, Enos Mills claimed that national parks promoted every positive attribute a person could imagine, from health to knowledge, from thinking to suppressing prejudice, from stimulating patriotism to ending vice and crime. Put simply, national parks offered what was good for people. Since national forests protected watersheds and promoted wiser use of timber and other resources, Americans felt that national parks needed a similarly practical justification. Convincing people to have fun took work. Seeking pleasure in an acceptable manner and in the right frame of mind took education. So once parks were created, promotion and publicity followed. People had to be encouraged to experience life in a wilderness preserve. "I wish that everyone might have a night by a campfire at Mother Nature's hearth stone," Enos Mills suggested. "A campfire in the forest marks the most enchanting place on life's highway wherein to have a lodging for the night." [12] Whether visitors entering Rocky Mountain National Park would sit by a campfire, ride a horse down a trail, meander through a meadow, or lounge at a lodge would not be decided by Enos Mills alone. Nor would Acting Supervisor Trowbridge make every decision affecting future travelers. How people entered the Park, what they saw, who they spoke with, how long they stayed, what impressions they gained, all these basic issues took park planners and promoters years to consider. Obviously, some people made these decisions for themselves. On August 7th, 1917, The Denver Post announced that George Desouris, self-styled as "the new Adam," intended to enter the "new Garden of Eden," searching for Eve. Wearing a primitive robe, "Adam" claimed to have had "a vision from heaven" directing him to enter the Park and join the Eve of Estes in her quest of living with nature. Supervisor Way, quoted by the Post, merely retorted: "Adam won't think he's in the Garden of Eden if he comes here." He said his rangers would not tolerate anyone molesting the adventurous Agnes Lowe. [13] Like Miss Lowe before him, Adam thought he had discovered the best method of enjoying a national park. Adventurers pretending to be Adam and Eve in paradise were not quite what national park idealists had in mind. More typical perhaps was a journey made by J. W. Willy and his son Knight in 1916. Their trip through the Park that summer began with a stay at the Stanley Hotel. In Estes Park father and son went on short hikes and made a special trip to meet the great naturalist, Enos Mills. Their second night was spent at the Horseshoe Inn where they met Shep Husted, "the famous guide of the Rocky Mountain region." Joined there by another tourist, Daniel Tower of Michigan, Willy, his son, and Husted mounted horses and embarked upon a journey across the mountains. They traveled along the Ute Trail, crossed the Divide, and reached Poudre Lake where they spent the night in a ranger cabin. The next day they rode their horses up Specimen Mountain, Shep Husted offering tidbits of geological history along the way. Then they descended to the western slope, spending the evening at "Squeaky Bob's." There they discovered that many other people had made the same journey. "They keep a-coming and a-coming," Bob complained, "and I can't turn 'em away (in) this weather." Bob Wheeler's resort reminded Willy "of country hotels of a century ago" with all its frontier flavor. Among its rustic elements, he noted that the "toilet paper fixture at Squeaky Bob's carries a big mail order catalog." [14]

After sleeping two to a bed in one of Wheeler's tents, the men rode northward to the headwaters of the Colorado, crossed Thunder Pass, and ascended Lulu Peak. After a second night at Squeaky Bob's, they traveled to Grand Lake. There they stayed at the Nowata, one of five hotels in operation. It featured "hot and cold running water in the rooms, bath, and a very good table; the rate $3.00 a day." Willy and his son explored nearby sights afoot, later complaining that trails needed to be cleared. He also noted that automobile travelers were bringing changes to these resorts, with more mobile travelers inclined to spend only one night rather than a week as guests had in previous years. Willy saw hotel keepers inconvenienced and higher prices resulting from such quick visits. The next day Husted guided his party across the Flattop Trail, down to Bartholf Park (today's Glacier Basin), then over Storm Pass to Longs Peak Inn, making a thirty-two mile ride. From there, Willy and his son departed for home. Their seven-day stay in the region encompassed a hundred miles on horseback and seventy-five miles hiking. Following their ambitious excursion, Willy offered a suggestion. "Whenever there is an automobile road in a national park," he urged, "it should be paralleled with a trail for the exclusive use of those who go afoot or on horseback. . . ." [15] Not every proposal or plan for the uses of the Park were as reasonable as Willy's, however. In January of 1915, for example, Congressman Albert Johnson of Washington suggested that Rocky Mountain National Park would be an ideal spot for a "leprosarium," by which he meant a national leper reservation. "The national parks are intended for recreation," The Denver Post snapped in reply. That "pinhead from Washington," the Post argued, totally misunderstood the purpose of having parks. [16] Less controversial requests came from hay fever patients who wished to build cabins, "to seek asylum above the weeds every season for about two months." [17] But those proposals met a similar fate. Interior Department officials replied tartly that no cabins would be constructed, nor would cattle be grazed, nor prospecting allowed, nor farming permitted, nor summer resorts built. Clearly, national parks could not satisfy everyone. On September 19th, 1916, Supervisor Trowbridge completed his organizational assignment and turned Park administration over to L. Claude Way, designated "Chief Ranger in Charge." A former Army captain and forest ranger, Way had worked at the Grand Canyon prior to his Rocky Mountain appointment. Some of his later critics claimed he brought an "arrogant" military style too harsh for a national park. Others said that he failed to communicate park policies to local residents, leading to disharmony. In fairness to Way, it should be noted that few policies existed for him to communicate.

Chief Ranger Way discovered that the Park was already immensely popular. Trowbridge earlier estimated that 51,000 people entered the Park in 1916. In 1917, Way reported that some 120,000 visitors arrived, bringing with them nearly 20,000 automobiles. Two years later his report showed 170,000 people entering the area. Officials boasted that Rocky Mountain National Park drew more people "than the combined tourist patronage of Yellowstone, Yosemite, Glacier, and Crater Lake Parks." [18] Rocky Mountain's easy accessibility from the East and Midwest made it an instant success. The need to serve so many visitors led L. Claude Way and other Park Service officials to ask Congress for increased appropriations. More rangers were needed, the public demanded better roads, camping areas had to be developed, the trail system was deemed "incomplete," and quarters for the Park staff had to be constructed. None of this could occur without more money, and a promise to hold spending at $10,000 annually, made during the passage of the Park's organic act, quickly proved to be a liability. Joining other citizens, Enos Mills sympathized with the Park Service. "I am starting a campaign to have an increased appropriation for this Park," he wrote in 1918. Yet the Park Service still gloried in Rocky Mountain's early popularity, and the increasing enthusiasm for national parks in general put pressure on Congress to increase funding. In March of 1919 Congress removed the $10,000 spending limit, finally making money for improvements available in 1920. Until then, Chief Ranger (later Superintendent) Way did his best to maintain the Park with the limited money and manpower available.

Like the need for money, regulations grew from necessity. Increasing numbers of automobiles entering the Park, for example, necessitated some rules, even though Park roadways totaled only sixty miles in 1919. Aside from demanding "careful driving of all persons," the regulations issued in 1918 limited speeds to twelve miles per hour, or ten miles per hour when "descending steep grades." Horns had to be sounded at every curve and "before meeting or passing other machines, riding or driving animals, or pedestrians." Every vehicle had to be "in first-class working order," capable of making the trip, with "sufficient gasoline in the tank to reach the next place where it may be obtained." Meeting horse teams along the roadways demanded extra caution. Regulations of this type helped, but accidents still happened. "Numerous collisions occurred between automobiles," Superintendent Way reported in 1918, "and between automobiles and saddle horses, none of which resulted in more than slight damage." [19] A new regulation in 1919 restricting the public conveyance of visitors exclusively to Roe Emery's Rocky Mountain Park's Transportation Company gave Superintendent Way a real taste of controversy. That regulation resulted from the desire of National Park Service Director Stephen Mather to provide reliable public transportation services for visitors. Just outside the boundaries of many national parks, independent drivers offered to transport travelers to local hotels or to take them on sightseeing excursions. Visitors complained that some of those operators cheated the public, provided "indifferent service," failed to keep their schedules, or would not run unless their vehicles were full. Park Service officials concluded that a public transportation system would best operate through one company in each park. Applying that new policy to Rocky Mountain National Park, the Park Service granted the Transportation Company a virtual monopoly. Local entrepreneurs around Estes Park and Grand Lake were incensed. In an era of free enterprise and of "trust busting," granting a local monopoly in the name of "efficient service" appeared to be almost tyrannical. Among the most critical was Enos Mills. Angered by the granting of this new concession with exclusive privileges, which now applied to an area long used by local resort owners, Mills fumed: "Our national park policy governs without the consent of the governed." "The Director of the National Park Service," he concluded, "is farming these parks out to monopolies." Years of debate verging on acrimony followed. Mills championed the rights of "numerous resident local people who earned their living serving visitors." [20] Superintendent Way found himself caught in a crossfire, defending a national policy he had not created. Nevertheless, the new National Park Service would not recant; it flexed its muscles by emphasizing its concern for the greatest good for the greatest number of visitors. This controversial regulation also proved to be difficult to enforce. People like Mills were willing to challenge Superintendent Way, his rangers, and the National Park Service in more than just debates. Unauthorized vehicles carrying passengers were deliberately sent into the Park to test the new policy. Rangers arrested offending drivers, court cases resulted, and the noisy controversy lingered. Not until 1926 did the state of Colorado dismiss suits against the federal government related to this issue. And by then a larger issue had surfaced: who controlled the roads in the Park? The state, and Grand and Larimer counties built those roads before 1915, with the Fall River Road not completed until 1920. Colorado had not ceded jurisdiction to the federal government. Granting a monopoly grew more complex, and it was a concept some local businessmen felt they could not accept. At the same time, idealists in the new National Park Service merely planned to provide better transportation for the public. While less than 15 percent of all Park travelers used Transportation Company services, the imposition of a national policy that upset local economics raised serious questions.

While wrangling over the monopoly issue, Superintendent Way might have written the phrase, "Tempted to give up but didn't," a cryptic message that in fact came from the Eve of Estes, Miss Agnes Lowe. Etched with a piece of charcoal upon bark and placed upon a trail in a conspicuous fashion, that phrase joined the words, "Nearly froze last night." She was keeping a curious world informed. "Have fire now. Feeling fine," completed her words from the wilderness. According to The Denver Post of August 9, 1917, those notes and a brief sighting by four parties of tourists confirmed that Miss Lowe was alive. She was spotted "roaming thru the sunshine 'a la Nature.'" Reportedly, she quickly donned her leopard's skin, displayed a good sized string of trout, and paused only long enough to describe an encounter with a brown bear. [21] Four straight days of such reports, with a tale or two about Adam, meant that readers across the country could pinpoint Rocky Mountain National Park on their maps. Advertising this new park became one of many tasks undertaken by the National Park Service between 1915 and 1929. One of their recurring advertisements during that era brought the latest news about roads as vacationing by automobile flourished in the post war period. Promoters saw the completion of the Fall River Road as providing a vital link for tourist travel through the region. Superintendent Way met constantly with state officials between 1917 and 1920 urging this project toward completion. Based upon prior agreements, when the state finished the Fall River Road it was to be turned over to the federal government. Late in 1920 the National Park Service proudly announced that "the outstanding event of the year was the completion of the Fall River Road connecting the east and west sides of the park." News that a new route over the Rockies had opened spread quickly. Visitation to the Park jumped accordingly, "reaching the enormous total of 240,966 visitors" in 1920. [22] While this roadway beckoned thousands of travelers, its rugged and narrow nature made it more challenging than enchanting. Numerous switchbacks "with exceedingly sharp curves" as well as steep grades and a "roadbed too narrow to admit of safe two-way traffic" were combined with long sections of bogs and bumps." [23] Almost immediately Park officials started working to make improvements. Removing snow each spring proved to be one of the most laborious tasks. In 1921, for example, crews spent more than a month clearing snow to insure that travelers could use the route by mid-June. Near Fall River Pass, crews encountered a drift 1,200 feet long, 25 feet deep. That season alone, two tons of dynamite were used to clear the road. Soon the Park acquired a steam shovel to assist the crews shoveling tons of snow by hand. Even then, early in the season teams of horses had to drag many of the first busses and autos across some sections of the road. Costs of keeping this road passable became a major item in the Park budget. While national park officials heralded the scenic aspects of this route across the Rockies, it demanded a continuous drain on money, manpower, and maintenance. Dozens of lesser activities, many promoting recreation and preservation, also got a boost in the 1920s. Rangers kept a concerned eye on Park wildlife, attempting to provide accurate counts of sheep, deer, and elk. They lured some animals closer to roadways by placing salt blocks at certain locations, believing that these "tame" animals served an educational function for the public. In 1918, Superintendent Way reported: "The frolicking lambs are especially interesting to travelers and convince the great majority of them that the kodak furnishes more real and lasting pleasure in game hunting than the gun." [24] An Interior Department biologist linked wildlife and Park publicity more directly: "The greatest advertising any national park obtains is the number of pictures taken by visitors and given wide distribution. This is the most effective method of advertising—the more so because the intent is not apparent." He suggested that fenced enclosures be placed near roadways, keeping animals of various species on display. "An exhibition inclosure of wild animals," he concluded, "greatly increases the number of pictures taken by visitors." [25]

Though rangers worried about protecting some animals, they worked toward the destruction of others. For example, they watched over the herds of sheep, elk, and deer like guardian angels; they looked for poachers and patrolled the boundaries every hunting season. During the winter of 1917, when food appeared scarce, they even went to the trouble of sawing open a beaver house and dumping in some tasty treats. But meanwhile they waged war on "undesirable" species. Throughout the 1920s such predatory animals as mountain lion, fox, bobcat, coyote, and marten were killed. Some animals were loveable; others made the mistake of preying upon those beloved. Planting fish in lakes and streams became one of the most active and popular programs of the era. Fishing always ranked high on everyone's recreational list. Park officials hoped to increase the chance that no fisherman would go away disappointed. Through cooperation with nearby state hatcheries, rangers stocked from one hundred thousand to a million trout in Park waters each year.

Diverse forms of recreation also received attention. In addition to extending trails, improving roads, and creating campgrounds, Superintendent Way and his staff assisted the Colorado Mountain Club in its well-advertised winter outings at Fern Lake by building ski trails and toboggan slides and by assisting when accidents occurred or when people became lost. Wintertime use of the "playground" received its first boost when officials noted that "skiing, ski-jumping contests, snowshoeing, skating, and tobogganing were the most popular amusements" among people coming to enjoy winter recreation. Promoting many "improvements" and activities while providing "excellent service" kept Superintendent Way and his rangers busier than ever. By 1921, the rangers numbered four permanently assigned men and six more added each summer season. Helping develop sites that promoted popular forms of recreation fulfilled their ideal of a park. Wilderness and preservation tended to provide a useful backdrop for action. At the heart of most activity ran the Fall River Road, renowned for its "scenery and far-flung panoramas," having "few peers and no superiors." [26]

Having established some trends toward development and tasting a controversy or two, Superintendent Way decided to return to cattle ranching in Arizona. He resigned on October 24th, 1921. Succeeding L. Claude Way was Roger W. Toll, a popular man who was able to soothe local tempers, resolve a few disputes, and at the same time make National Park Service policies more effective. Throughout the 1920s, Roger Toll committed himself to making Rocky Mountain National Park even more popular with the public. Born in 1883, Toll was the son of a Denver attorney. Like other Denverites, Roger Toll spent much of his youth exploring the Rockies nearby. His knowledge of Colorado contributed to his popularity among residents of Estes Park and Grand Lake. After obtaining a civil engineering degree from Columbia University in 1906, Toll spent a year traveling around the world. He worked in Massachusetts and Alaska prior to returning to Colorado where he became chief engineer of Denver's tramway company. When the Colorado Mountain Club organized in 1912, Toll joined as a charter member. In the years that followed, he compiled a guidebook about his hobby, later published as Mountaineering in Rocky Mountain National Park. That book caught the attention of National Park Service Director Stephen Mather. In 1919, Mather asked Toll to become superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park. There Toll proved to be a good administrator, an active mountain climber, and a leader in such local organizations as the Mountaineers. In 1921 he accepted the appointment of superintendent at Rocky Mountain National Park. Among dozens of people voicing enthusiasm for Rocky Mountain National Park during the 1920s, Roger Wescott Toll was probably the most prominent. Being an adventurous mountain climber, Toll rambled throughout the range, taking photographs and making notes, ascending one peak after another. As an active writer Toll produced numerous articles about the Park and became the Park's chief publicist. He wrote promotional stories describing Park scenes, telling potential tourists what they might find. His articles suggested new development projects, convincing the public that the National Park Service had its welfare in mind. He explored historical topics and described recreational opportunities. His themes helped inform and educate the public, always making Rocky Mountain National Park look exciting and attractive to the potential tourist. In Roger Toll, national park idealism found both a practitioner and a spokesman. "Along with the recreational value of the parks," he wrote, reflecting his own mountaineering experience, "is their health giving value and their inspirational value." He observed: "It has been said that great views create great thoughts and great thoughts create great men." [27] Toll tried mixing his publicity with a philosophy both practical and hopeful. Under Roger Toll's guidance, Rocky Mountain National Park entered its modern stage as a center for wide-ranging recreational activities. Although rigorous mountain climbing and hiking were among Toll's favorite pastimes, he also recognized that some people might find a mere automobile ride along the Fall River Road equally inspiring. Staying at a lodge within or near the Park, whether at F. W. Byerly's Bear Lake Camp or at Mrs. McPherson's Moraine Lodge or at one of several dozen other resorts, remained the classic way to enjoy the region. Camping at spots such as Aspenglen, Pineledge, Glacier Creek, or Endovalley, all developed by 1926, became more popular as visitors sought both inexpensive outdoor vacations and a campfire. By 1922, ranger-naturalists were conducting "all-day nature study trips" in an effort to provide an educational dimension to national park visits. Evening talks proved to be instantly popular, with lantern slides adding a visual treat. The public gave the naturalists encouraging reviews, expressing an even greater desire "for more accurate and complete knowledge with reference to natural history subjects." [28] A variety of new books helped answer an increasing demand for information, covering subjects as diverse as geology, birds, plants, Indians, and mountaineering. Newly produced maps also appeared. A curious public arriving with probing minds stimulated many avenues of research and education. Roger Toll also managed an ambitious building program. A new administrative office appeared in 1923, along with a machine shop, a warehouse, a mess hall, and dwellings for National Park Service employees. The main Park utility area started taking shape. Camps for road workers were built at Horseshoe Park and Willow Park; checking stations were placed at the Fall River and Grand Lake entrances. Ranger stations were built at Twin Owls, Bear Lake, Fern Lake, and Horseshoe Park to augment older stations like those at Pole Creek and Mill Creek which had been inherited from the Forest Service. Shelter cabins at Fall River Pass and on Longs Peak were also constructed. Backed by steadily increasing National Park Service appropriations, Roger Toll helped produce a plethora of projects, all viewed as helpful or necessary steps toward progress. Of course Superintendent Toll was not the sole advocate of building for the future. National Park Service planners contributed many ideas. And most of Toll's contemporaries applauded these many developments. Local businessmen, newspapers, and politicians welcomed any federal effort to increase the popularity of the Park. Very few people worried about overdeveloping the region or introducing too many comforts of civilization into an area also intended as a wilderness preserve. As early as 1922, however, Assistant Park Service Director Horace Albright responded to an expressed fear of "over-development of the National Parks in the future by too many roads, hotels, etc." Albright reported that the national park superintendents "were unanimous in their belief that certain wild sections of every park should be forever reserved from any development except by trails, first because the National Parks are destined to soon be the only sections of wilderness left in America, and second because wildlife thrives best in untouched wilderness." [29] Amid the bustle of construction, a few people still pondered the problem of preservation.

Meanwhile, private enterprise surrounding the Park energetically prepared for the future too. Trends born in previous decades gained momentum. The 1920s saw numerous cabins built around Estes Park and Grand Lake. Additions came to many resorts. More shops and businesses catering to travelers sprouted. One classic example of resort development occurred on the Park's western slope, at a ranch site first called Holzwarth's Trout Lodge. John G. Holzwarth, a German immigrant, had been a successful Denver saloon-keeper until wartime Prohibition put him out of business. Around 1917, Holzwarth and his wife Sophia decided to move into the mountains, establishing a homestead along the Colorado River north of Grand Lake. There on the North Fork the Holzwarths and their three teenaged children cut timber, built a sawmill, and erected a cabin. Their original idea was to develop a ranch, raising both hay and horses. Trapping for furs and freight hauling helped bring in extra money.

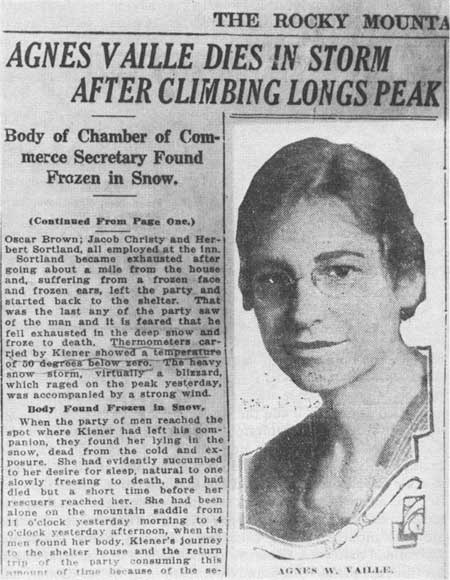

In about 1920 a few of Mr. Holzwarth's "drinkin' friends" from Denver made a visit to the homestead to do some fishing. That group proved to be "so lazy and drunken that they even quarreled over the division of the fish." Once that bunch left for home, Mrs. Holzwarth and son Johnnie "rebelled" at having to cater to such ill-mannered people. Future guests, they insisted, would have to pay. They christened their homestead the Holzwarth Trout Lodge and began charging two dollars a day or eleven dollars per week. A dude ranch was born. Rental cabins soon offered visitors some rustic shelter and Mrs. Holzwarth provided filling meals. This infant business found a steady clientele and thrived, growing larger during the decade. The Never Summer Ranch, as it was called by 1929, continued as a prosperous example of the 1920s until it was purchased by The Nature Conservancy in 1974 and transferred to Rocky Mountain National Park in 1975. Dozens of other businesses similar to the services offered by the Holzwarths grew as more travelers explored the region. Not every Park visitor had a good time, however, regardless of people such as the Holzwarths or Superintendent Toll and his rangers. Sometimes nature proved to be a harsh host. In 1922 and again in 1923, for example, lightning struck hikers on Longs Peak. J. E. Kitts was killed outright by a strike as he stood on the summit. Ethel Ridenour, hiking to Chasm Lake, was hit by lightning, burned severely, rendered unconscious, and upon recovering, suffered the permanent loss of one eye. But accidents did not alter the popularity of climbing Longs Peak; in 1929 alone, more than sixteen hundred people signed the register at the summit. Superintendent Toll and the National Park Service fully recognized the dangers of mountain climbing. Yet all their advice and warnings sometimes went unheeded. In January of 1925, for example, Miss Agnes Vaille intended to become the first woman to scale the east face of Longs Peak in wintertime. Since the east face was an awesome challenge even in good summer weather, she tempted disaster. Vaille made three tries at the summit in the three previous months, failing each time. January found her more determined than ever, although "friends sought in vain to dissuade her from her plans." She found a companion in Walter Kiener "an experienced mountaineer of Switzerland." On Monday, January 12, 1925, they made that remarkable climb, achieving success by way of the Couloir, Broadway, and a chimney just west of Notch Chimney. But Vaille's hard-won victory was short lived. There on the summit, she and Kiener found the temperature at fourteen below zero and a wind "blowing a terrific gale." Quickly they descended along the easier north side. Soon after, fatigue started clouding her brain. According to Kiener, Agnes Vaille "insisted that she was so sleepy and was going to take a rest and a short nap." Kiener went for help, but when a rescue party found her, she had already frozen to death. For his part, Kiener himself lost most of his fingers and toes as well as part of one foot to frostbite. And compounding the tragedy, Herbert Sortland, a volunteer member of the rescue team, disappeared while returning to Longs Peak Inn. His body was not found until February 27th. A local paper considered the unfortunate Sortland a "martyr to humanity." [30] Yet almost no one publicly criticized either Vaille or Kiener for attempting such a hazardous climb, even though they risked the lives of others. Perhaps people decided that Agnes Vaille had paid the ultimate price for her reckless adventure.

Facing the reality of accidents that came with increasing climbing activity, Superintendent Toll proposed building a shelter cabin high on Longs Peak at the Boulderfield. As a result, in 1927, National Park Service crews constructed a sturdy stone structure that operated as a chalet-type concession until 1935. In memory of Agnes Vaille, another rock-walled shelter was built, this one placed near the Keyhole. Deaths on Longs Peak and elsewhere in the Park meant more active patrolling by rangers. Rescue work started playing a larger role in their jobs. Nevertheless, enthusiasts publicizing the Park continued to encourage vigorous recreation. "Mountaineering, in its broader sense," Roger Toll claimed, "promotes the health and strength of the body, it teaches self-reliance, determination, presence of mind, necessity for individual thought and action, pride of accomplishment, fearlessness, endurance, helpful cooperation, loyalty, patriotism, the love of an unselfish freedom, and many other qualities that make for a sturdy manhood and womanhood." [31] Accidents were a small price to pay if people truly sought such noble qualities. A number of deaths, caused by carelessness or a lack of caution, would periodically plague the Park in succeeding years. Thus words of advice coming from National Park Service spokesmen mixed a zeal for wilderness recreation with a dose of concern for safety. Based upon a decade's success as a popular park, Roger Toll proposed an expansion of Rocky Mountain in 1925. The original 1915 boundary lines had already been moved in 1917 to include such areas as Gem Lake, Deer Mountain, and Twin Sisters. The Park grew to include 397.5 square miles. By the mid-1920s, the Park boundaries also surrounded some eleven thousand acres of private land, making administration of the area more complex. Seeing an increasing popularity of the Park, the National Park Service hoped to annex adjacent Forest Service land. Superintendent Toll and other Park Service planners suggested that the Park expand southward to include the region of Arapahoe Glacier. Toll also believed that the Never Summer Range to the West would fit nicely into an enlarged park of the future. Toll's plans for expansion were not accepted with unanimity. Like the heated transportation controversy or the question of who owned the roads, a larger park was seen by some Coloradans as further endangering their rights to water, private property, mining, and economic prosperity in general. Cooler heads pointed out that tourist dollars meant prosperity too. A local editorialist summed up the opposition to the expansion program: "There is so much that is wrong with administrative policies and regulations of the National Park Service that Boulder will vigorously fight to be kept from being sacrificed on the destructive altar dedicated to federal red tape and monopoly." [32] Wary of their critical neighbors, Park officials pursued boundary expansion somewhat less zealously.

Contributing to this atmosphere of acrimony was the issue of the state ceding jurisdiction over Park roads. Colorado's concern ranged from a theoretical loss of state's rights to a fear that entrance fees would be charged. Losing control of the roads was also tied to a possible prohibition of future water projects. "It would be unwise and foolish," one opponent of the Park noted, "to let a monopoly-granting, fee-charging Federal Bureau like the National Park Service become the absolute czar of State-built, State-owned roads leading to and through the Rocky Mountain National Park." With a touch of melodrama, he concluded: "Abolish the Park if you wish! A rose by any other name will smell as sweet! Czarist Federal encroachment on the rights and property of States must stop!" [33] Not until February 16, 1929 did Colorado finally agree to cede its rights to Park roads. Soon after, on March 2nd, 1929, the federal government gladly accepted that cession. Years of debate over that awkward management of roadways finally ended. With the best of intentions, National Park Service planners had helped expedite the conclusion of that debate. They proposed building another scenic road across the mountains, this one by-passing the narrow and twisting Fall River Road. Their proposed route lay along Trail Ridge. By the mid-1920s, Park Service Director Stephen Mather had little trouble demonstrating the popularity of the national parks; dramatic increases in the number of people visiting the parks proved his case. Congress at last started listening to his budget requests. Soon substantial appropriations were available for improving roadways, an item always greeted enthusiastically by the public. While the jurisdiction question went unresolved, only old roads were fixed. No new construction could take place. Efforts to modernize the Fall River Road proved fruitless, since its narrow, winding course defied improvement. An alternate route soon became a reasonable suggestion. In August of 1926, the Bureau of Public Roads initiated a survey across Trail Ridge. Just as the jurisdiction issue reached its final stages of debate in October of 1928, plans were presented for "one of the greatest scenic park highways in the entire United States." The start of this project, however, depended upon Colorado's willingness to cede its jurisdiction over Park roads. Rather swiftly, that old bureaucratic blockade was cleared. Newspapers lauded this "one-half-million dollar project" as a new sign of federal concern for the region. [34] The beginning of Trail Ridge Road marked the end of a decade of promotion and development. In January of 1929, the energetic Roger Toll accepted an appointment as superintendent of Yellowstone National Park. When he left Rocky Mountain, it was well established as a booming recreational area. Park boundaries had been adjusted a bit; numerous facilities and services for visitors appeared; modern highways took shape; several sticky controversies were resolved; protection was enhanced for both wildlife and mountaineers. Promoting the Park was paying off in increasing popularity and greater numbers of visitors. In 1929, nearly three hundred thousand people entered the Park.

On August 13, 1917, The Denver Post reported that the Eve of Estes had returned to civilization after her week in the woods. "Sunburned almost of the shade of pine bark, and covered with mosquito bites from the crown of her head to the soles of her feet," came the story, she appeared in perfect health "and weighed a half pound more than when she left civilization." [35] According to the Post, her adventure produced dozens of stories in newspapers "from Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon, and from Hudson Bay to Key West, Florida." [36] After being welcomed back by Park officials and Enos Mills, and posing once again for cameras, Agnes Lowe was given a mail sack containing sixty-four proposals of marriage. With the adventure at an end, she left for a local lodge to rest. She rapidly returned to obscurity, leaving only a week's worth of newspaper columns in her wake.

Whether those columns spelled positive publicity for the Park was debatable. Within a week, Park Service officials in Washington were fuming at this "frame-up for publicity purposes." Called upon by superiors to explain his participation, Superintendent Way immediately blamed "the Denver Post and the Hearst Syndicate," although he felt the stories "will result in very valuable publicity and undoubtedly in bringing hundreds of people to this park." [37] Rather than receiving praise for his role, Way then heard from Assistant Director Albright. Albright claimed that stunts of that type "will surely bring adverse criticism upon park management." He added that "a national park is not the proper stage for even this sort of thing." [38] Faced with a barrage of criticism, Way confessed to being duped into helping reporters from The Denver Post arrange the stunt. He admitted watching as "Eve" arrived at Longs Peak Inn and as she posed for photographers in preparation for her adventure. But rather than watch her disappear into the mountains alone, Way arranged for one of his rangers to take her to Fern Lodge. There she stayed until Way himself escorted her back to Estes Park that following Wednesday. He admitted that her emergence from the forest that next Sunday was entirely a staged affair. The whole event had been a fraud. But once again Way argued that the stories "did no real harm and aroused interest in the Park and would bring people here who would enjoy themselves and be benefitted." [39] Like the unamused Park Service officials in Washington, ranger R. A. Kennedy disagreed. Kennedy considered it an unpleasant task to escort Miss Lowe to Fern Lodge. "It is cheap and disgusting, and smacks more of a cabaret than a wholesome advertisement," he concluded. [40] Whether it was really "cheap and disgusting" or merely amusing, Rocky Mountain National Park had hit the headlines. Trying to make a park for all to enjoy meant making a few mistakes, having a few embarrassments. Success and popularity came regardless, in part because of the efforts of such people as Roger Toll, but mostly because the sublime beauty of Rocky Mountain National Park could not be diminished by ill-conceived publicity stunts. Roger Toll knew this well: "Surely if one can ever grasp the infinity of time and space, it is here, standing on the peak and looking off to the vanishing horizon." [41]

|

| <<< PREVIOUS | CONTENTS | NEXT >>> |

Rocky Mountain National Park: A History ©1997, University Press of Colorado All rights reserved. This text may not be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the University Press of Colorado. buchholtz/chap6.htm—26-Dec-2006 | ||