.gif)

MENU

The Wawona Hotel and Thomas Hill Studio

Yosemite

Bathhouse Row

Hot Springs

Old Faithful Inn

Yellowstone

LeConte Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

El Tovar

Grand Canyon

M.E.J. Colter Buildings

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Depot

Grand Canyon

Great Northern Railway Buildings

Glacier

Lake McDonald Lodge

Glacier

Parsons Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

Paradise Inn

Mount Rainier

Rangers' Club

Yosemite

Mesa Verde Administrative District

Mesa Verde

Bryce Canyon Lodge

Bryce Canyon

The Ahwahnee

Yosemite

Grand Canyon Power House

Grand Canyon

Longmire Buildings

Mount Rainier

Grand Canyon Lodge

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Park Operations Building

Grand Canyon

Norris, Madison, and Fishing Bridge Museums

Yellowstone

Yakima Park Stockade Group

Mount Rainier

Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence

Crater Lake

Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District

Bandelier

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves

Northeast Entrance Station

Yellowstone

Region III Headquarters Building

Santa Fe, NM

Tumacacori Museum

Tumacacori

Painted Desert Inn

Petrified Forest

Aquatic Park

Golden Gate

Gateway Arch

Jefferson National Expansion

|

Architecture in the Parks

A National Historic Landmark Theme Study |

|

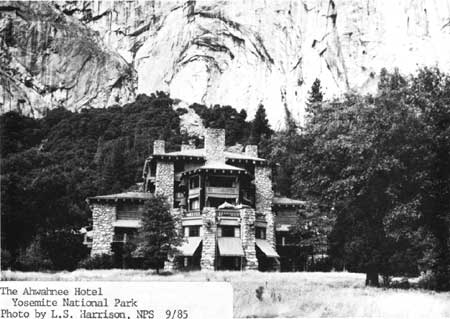

The Ahwahnee Hotel, Yosemite NP, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

The Ahwahnee Hotel

| Name: | The Ahwahnee Hotel |

| Location: | Yosemite National Park |

| Owner: | Yosemite Park and Curry Company |

| Condition: | Good, altered, original site |

| Classification: | Building, private, accessible (restricted), luxury hotel |

| Builder/Architect: | Gilbert Stanley Underwood (for the Yosemite Park and Curry Company) |

| Dates: | 1925-present |

DESCRIPTION

The Ahwahnee is an enormous luxury hotel at the east end of the Yosemite Valley. Sited in a meadow, the building's large scale is diminished by the awesome beauty of the sheer granite cliffs of the north valley wall above. The building's name comes from a local Indian word meaning "deep, grassy meadow."

The building has an irregular, asymmetrical plan that is Y-shaped and contains 150,000 square feet. Primary building materials are rough-cut granite and concrete. The uncoursed granite rubble masonry of the piers matches the color of the adjacent cliffs. What looks like wood siding and structural timbers between the piers is actually concrete, poured into formwork that shapes it to look like horizontal redwood siding and large milled timbers. The stain on the concrete, similar in color to pine bark and redwood lumber, reinforces that illusion that the fabric is wood.

The building is massed into several enormous blocks with a six-story central block and wings of three stories. The multiple hip and gable roofs are finished with green slate and further break up the building's form, making it appear as rough and textured as the surrounding landscape. The building has balconies and terraces at several different levels that add a spatial interest not only to the exterior but also to the visitor experiencing the interior of the building. The building contains approximately 95 guest rooms, various public spaces and meeting rooms, an enormous dining room, and utility spaces. The principal entrance to the building is through a porte-cochere on the north side of the building. The log and wood entrance contains painted decorations in Indian patterns, setting a tone for the interior. This entrance serves mainly as a utilitarian space to funnel the visitor to the building's interior, and to the views of the grassy meadow to the south and the impressive vistas, seen from most of the rooms. The main entrance is more subdued than noteworthy; the most impressive views of the hotel are from the southern meadows.

The north wing of the hotel contains the lobby, decorated with floor mosaics of Indian designs executed in brightly colored rubber tiles. The cornice is stenciled with Indian-design paintings. The elevator lobby continues the Indian designs with sawn-wood reliefs on the elevator doors and an abstract mural based on Indian basket patterns over the fireplace in that room. The Great Lounge's 24-foot-high ceiling has exposed girders and beams painted with bands of Indian designs. The exposure of the ceiling's structure gives the spatial impression of a coffered ceiling. The enormous fireplaces at opposite ends of the Lounge are cut sandstone. The wrought-iron chandeliers, Persian rugs hanging on the walls, and the wood furnishings are original. Their worth and delicate condition resulted in their conservation and placement in enclosed cases on the walls. Other oriental rugs, primarily replacements, are on the polished wooden floor of the Great Lounge. The floor-to-ceiling windows in the Great Lounge have 5x6-foot stained glass panels at the top, with handsome designs based on Indian patterns, but like many of the other interior elements done with a flatness found in Art Deco architecture.

Directly off the Lounge are the California Room, the Writing Room, and the solarium that overlooks the southern meadow. The California room contains decorations of memorabilia from the Gold Rush days. The Writing Room's principal feature is an oil painting on linen by Robert Boardman Howard that runs the length of one wall and depicts local flora and fauna in a style reminiscent of medieval tapestries.

The large dining room (6,630 square feet) has a gable-roofed ceiling 34 feet high at the ridge. The walls are massive granite piers interspersed with 11 floor-to-ceiling windows with the exception of the partition wall between the kitchen and dining room which has a six-foot wainscotting of wood panelling with plaster above. The sugar-pine roof trusses are supported by concrete "logs" again painted in imitation of the real thing. Original wooden furniture and wrought-iron chandeliers remain in use.

Also included within the boundaries of this nomination are the meadow directly south of the hotel, the stone gatehouse marking the entrance to the property, the parking lots, and the small pond and walkways at the building's entrance, directly north of the porte-cochere.

Changes to the hotel over time have been in keeping with the structure. The architecture, designed by Gilbert Stanley Underwood, was enhanced by the interior design directed by Drs. Phyllis Ackerman and Arthur Upham Pope. The stained glass work and mural over the fireplace in the elevator lobby were the work of San Francisco artist Jeannette Dyer Spencer. The Howard mural in the Writing Room, also produced under their direction, contributed to the medieval allusions that crop up throughout the building, particularly in the heavy-handed wrought ironwork.

These were all completed prior to the opening in July, 1927. The sixth-floor roof garden and dance hall was turned into an apartment for the Tressider family about 1928 after the area's function as a dance hall did not work. The apartment was remodelled again much later when a private guest suite and sunroom were added. The trusses in the dining room were beefed up in 1931-32 when the Company's architect discovered that they were minimally designed for the snow loads and earthquake stresses they needed to bear.

At the end of Prohibition in 1933 a private dining room on the hotel's mezzanine level was remodelled into a bar called "El Dorado Diggins" complete with false storefront and antiques from the Gold Rush days. In 1943 the U.S. Navy's takeover of the building as a convalescent hospital for war wounded resulted in major temporary changes to the grounds. When the Navy evacuated the structure they did considerable painting on the interior. The smaller maids' and chauffers ' rooms were remodelled into guest rooms after the War when fewer guests brought their own servants. In 1950 the original porte-cochere which had been enclosed by the Navy was remodelled into the Indian Room--a multi-purpose space for meetings, dances, and the like. The fire alarm system and exterior fire escapes also were added during the 1950s. In 1963 the outdoor swimming pool and automatic elevators were installed. All of the smaller windows in the building were replaced during the 1970s and some spalling concrete was repaired at the same time. Smoke detectors were installed in all rooms during the late 1970s, transoms above doors to guest rooms were sealed off, and fire doors were put on the exit doors to the fire escapes. At the same tine a sprinkler system was added to portions of the building--the local water supply could not support a complete system. The sixth-floor apartment which had been remodelled during 1970-71 underwent further remodelling in the early 1980s in preparation for the visit by Queen Elizabeth II at which time a new bath and new kitchen were added. The kitchen has been upgraded periodically over the building's history. Other utility areas retain original configuration and updated equipment.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

The principal significance of the Ahwahnee lies in its monumental rustic architecture. Inseparable from that architecture is the period art work and interior design so carefully executed throughout the building. Also of significance is its importance as the hostelry that has housed through its history dignitaries, movie stars, artists, and others having an impact on the twentieth century. Undoubtedly this is due to the Ahwahnee's place as the architectural gem of monumental luxury of a crown jewel of the National Park System. Of regional significance is the Ahwahnee's place in California history and the development of the concessions industry at Yosemite National Park.

In 1925 Stephen Mather provided considerable urging and $200,000 of his own personal fortune for two Yosemite concessionaires to merge into one company--the Yosemite Park and Curry Company. Mather had seem the need for a superior hotel at Yosemite but forced the merger because of the fierce competition between the two companies. Donald B. Tressider, later president of Stanford University, became president of the new company. The contract that the new company signed with the park service required the construction of a new fireproof hotel that would have the capability of year-round operation. Recommended as architect for the building was Gilbert Stanley Underwood of Los Angeles.

Underwood was an architect of considerable reputation and well known to Stephen Mather, Horace Albright, and others in the park service when he accepted the commission to design the Ahwahnee. Underwood began his professional career working for architects in the Los Angeles area who designed structures in every style from Beaux Arts classicism to Mission Revival. After attending a series of universities he finally received a Bachelor's degree from Yale, and then a Masters from Harvard. Underwood's first large works were for the Union Pacific Railroad on Zion and Bryce Lodges, followed by the Ahwahnee, Grand Canyon Lodge on the north rim, a series of railroad stations for the Union Pacific, Timberline Lodge, Sun Valley Lodge, and Williamsburg Lodge.

Underwood's other work included the San Francisco Mint, the Federal courthouses in Los Angeles and Seattle, and the first unit of the State Department Building in Washington.

Albright, Mather, and Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work and Donald Tressider chose the site for Yosemite's new hotel. Besides choosing an area unobtrusive in its setting yet with magnificent vistas, Albright commented:

We felt by offering a quiet, restful, spacious hotel that many well-to-do, influential people who had ceased coming to Yosemite, owing to the crowds, could be led to return to us again and that furthermore the Ahwahnee would give us a suitable unit in which to promote all-year business, offering the most luxurious comfort at all seasons of the year. [1]

Albright saw the building as a drawing card not only to increase tourism to Yosemite--and at that time park appropriations were directly related to numbers of visitors--but undoubtedly as a special haven for the important and influential whose backing of national parks was always welcome. After all, it never hurt to have friends.

In designing the building Underwood took great care in choosing the materials and the treatment of the materials. The stone, for instance, was weathered granite set in the wall with only the weathered face exposed. This treatment which appeared in the specifications for the Ahwahnee became standard park service practice in rustic buildings where masonry was used. The exposed concrete was designed to imitate wood in color, form, and texture. Underwood's blocky masses of the building that stepped up the structure to the penthouse gave the building a physical presence in architecture that was parallel to the presence of Half Dome in nature. Underwood succeeded in his assignment of designing a building that fit with its magnificent setting.

Work on the building progressed slowly and cost overruns were enormous. As the interior began taking shape the Yosemite Park and Curry Company hired Drs. Phyllis Ackerman and Arthur Upham Pope, experts in art history, to guide interior decoration of Underwood's cyclopean structure. They commissioned Jeannette Dyer Spencer's stained glass windows in the Great Lounge and basket-design mural in the Lobby. They had Robert Boardman Howard paint a subdued mural for the writing room reminiscent of medieval tapestries. They personally chose the killims and Persian rugs used on the interior. Photographer Ansel Adams was so taken with the building that he wrote:

. . . yet on entering The Ahwahnee one is conscious of calm and complete beauty echoing the mood of majesty and peace that is the essential quality of Yosemite. . . . against a background of forest and precipice the architect has nestled the great structure of granite, scaling his design with sky and space and stone. To the interior all ornamentation has been confined, and therein lies a miracle of color and design. The Indian motif is supreme . . . . The designs are stylized with tasteful sophistication; decidedly Indian, yet decidedly more than Indian, they epitomize the involved and intricate symbolism of primitive man . . . [2]

When the Ahwahnee opened its doors to the public in July, 1927, the consensus was that it was worth the wait. The Ahwahnee became the impressive building that Mather wanted in those awesome surroundings. Through the years the building housed an enormous variety of people: movie stars, heads of state, artists, and influential politicians. The guest list included Dwight D. Eisenhower, Haile Selassie, the Shah of Iran, Herbert Hoover, Eleanor Roosevelt, Will Rogers, Gertrude Stein, Charlie Chaplin, Will Rogers, Lucille Ball, Ronald Reagan, Walt Disney, Greta Garbo, John F. Kennedy, and most recently Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip. Photographer Ansel Adams spent considerable time in the building, frequently breakfasting in the dining room while in residence at the park. Even today limousines remain commonplace in the parking lot. Perhaps more important than the list of dignitaries and famous people who have spent time in the Ahwahnee is the hotel's place as the heart of the aesthetic idea of Yosemite. The magnificent scenery of the valley is enhanced by the building's artful contributions to the ambience of the Yosemite experience.

FOOTNOTES

1 Zaitlin, Joyce, "Underwood: His Spanish Revival, Rustic, Art Deco, Railroad, and Federal Architecture," manuscript dated 1983 on file at National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office. Zaitlin quotes from Albright memorandum on the Ahwahnee Development, Olmsted Brothers file, Yosemite National Park Research Library.

2 Ansel Adams, untitled two-page typewritten document on the Ahwahnee, no date, pp. 1-2. On file at the Yosemite National Park Research Library.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

National Park Service files, Western Regional Office, including National Register files.

Sargent, Shirley. The Ahwahnee: Yosemite's Classic Hotel. Yosemite, California: Yosemite Park and Curry Company, 1984.

Tweed, William, Laura E. Soullière, and Henry G. Law. National Park Service Rustic Architecture: 1916-1942. San Francisco: National Park Service, 1977.

Yosemite Research Library and Records Center, Box #79, the Ahwahnee Hotel file.

Zaitlin, Joyce, Underwood: His Spanish Revival, Rustic, Art Deco, Railroad and Federal Architecture. 1983 Manuscript on file at the National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Regional Office.

BOUNDARIES

The boundary is shown as the solid line on the U. S. G. S. map and as the dotted line on the park planning map (both omitted from the on-line edition).

PHOTOGRAPHS

(click on the above photographs for a more detailed view)

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Feb 26 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/harrison/harrison15.htm

![]()