.gif)

MENU

The Wawona Hotel and Thomas Hill Studio

Yosemite

Bathhouse Row

Hot Springs

Old Faithful Inn

Yellowstone

LeConte Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

El Tovar

Grand Canyon

M.E.J. Colter Buildings

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Depot

Grand Canyon

Great Northern Railway Buildings

Glacier

Lake McDonald Lodge

Glacier

Parsons Memorial Lodge

Yosemite

Paradise Inn

Mount Rainier

Rangers' Club

Yosemite

Mesa Verde Administrative District

Mesa Verde

Bryce Canyon Lodge

Bryce Canyon

The Ahwahnee

Yosemite

Grand Canyon Power House

Grand Canyon

Longmire Buildings

Mount Rainier

Grand Canyon Lodge

Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon Park Operations Building

Grand Canyon

Norris, Madison, and Fishing Bridge Museums

Yellowstone

Yakima Park Stockade Group

Mount Rainier

Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence

Crater Lake

Bandelier C.C.C. Historic District

Bandelier

Oregon Caves Chateau

Oregon Caves

Northeast Entrance Station

Yellowstone

Region III Headquarters Building

Santa Fe, NM

Tumacacori Museum

Tumacacori

Painted Desert Inn

Petrified Forest

Aquatic Park

Golden Gate

Gateway Arch

Jefferson National Expansion

|

Architecture in the Parks

A National Historic Landmark Theme Study |

|

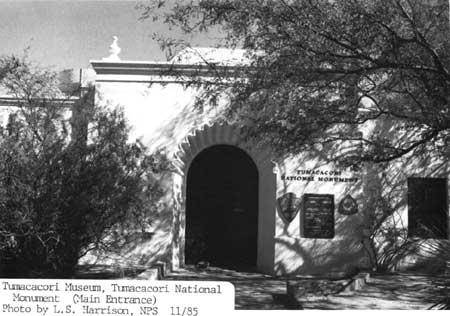

Tumacacori Museum (main entrance), Tumacacori NM, 1985.

(Photo by L.S. Harrison)

Tumacacori Museum

| Name: | Tumacacori Museum [preferred] (Tumacacori Visitor Center) |

| Location: | Tumacacori National Monument |

| Agency: | National Park Service Western Regional Office |

| Condition: | Good, altered, original site |

| Classification: | Building, public, accessible (unrestricted/restricted), government/museum/visitor center |

| Builder/Architect: | Scofield Delong, Charles D. Carter, and other NPS personnel |

| Dates: | 1937-present |

DESCRIPTION

Included in this nomination are the Tumacacori museum building, the comfort station, the museum garden, and the adobe walls surrounding them.

The Tumacacori museum building, also known as the visitor center/administration building is an adobe building on a concrete foundation with a concrete block addition at the end of the east wing. The generally T-shaped structure has ten rooms and comprises approximately 5500 square feet. To the north and south of the easternmost wing are arched portals (arcades)--one opening into the 1939 garden, the other looking out toward the ruins of the mission church.

The flat roof of the museum is surrounded by a parapet and drained by channels cut into the adobe piers of the portals. The roof is finished with a new four-ply built-up roof similar to the original. The roofline encircling the structure is finished with a stepped coping. Finials articulate the western corners of the building.

The main entrance at the west side of the building is through carved wooden doors set underneath an enormous shell motif in the reveal. The doors, carved by the Civilian Conservation Corps at Bandelier National Monument, feature floral designs used in other Sonoran mission buildings. The scallop-shell motif is seen even more frequently in Sonoran mission architecture, and symbolizes Santiago de Compostela, patron saint of Spain.

The main entrance leads into the museum lobby. The room has a corner fireplace at the southeast, and a floor of large bricks laid in a herringbone pattern. The ceiling beams are supported by carved corbels. The room also features handmade furniture of Spanish Colonial design, as do many of the other museum spaces. Some of the furniture is original to the structure, and the remainder was constructed in the late 1950s. The information desk is of recent construction and is triangular in shape. The original rectangular information desk was transferred to Coronado National Memorial. A small office south of the lobby is behind the information desk through an arch. The arch has been partially filled with a screen of wooden spindles which are removable and have not been attached to the structure.

The museum exhibit and audio-visual rooms have carpeting covering the original finish. The most important of the museum rooms is the "view room" which is an open-air room with a groin-vaulted ceiling. This room looks out to the mission church, and houses a scale model of the mission for comparison with the stabilized ruins. The original Spanish-Colonial design of the ceiling has been repainted with a hand not quite as steady as that of the original painter.

Construction began on the museum building in 1937 by contractor M.M. Sundt of Phoenix as a Works Progress Administration project. An addition of new offices and storage space was constructed on the eastern wing of the building in 1959. The addition's construction of concrete block finished with cement stucco was incorporated well into the museum building and is practically indistinguishable from the original building on the exterior because of its proper scale, design, and exterior finish. The additions contains approximately 430 square feet, less that 10 percent of the total area of the building. The remodelling was done by the construction firm of Krupp and Sons of Nogales, Arizona.

The patio garden, begun in 1939, is planted with plants similar to some of those grown in the missions of northern Sonora. In the center of the garden is a square fountain with small channel drains that lead off into the planted areas from the four corners. The meandering pathways through the garden have brick payers. Adobe benches provide resting places to the east and west of the fountain.

A seven-foot high adobe wall stretches north and south from the western wall of the museum. The wall screens all but the upper portions of the mission ruins from the road and parking lot, and thus serves as a security device, and also channels visitors through the main entrance to the museum. The northern end of the wall stops nearly at the monument boundary. South of the museum the wall is incorporated into the west and south walls of the comfort station, wrapping around that building toward the east and then the north enclosing the patio. An additional wall to the south of the comfort station runs east-west along the service road to the monument's housing area. The walls are adobe on concrete foundations, capped with flat and arched copings, and finished with stucco. The wall is pierced by openings in several places where multi-panelled doors provide access into the patio or the area of the former mission compound.

The comfort station is an adobe building constructed on a concrete foundation, just like the museum. The exterior is finished with cement stucco. The simple, rectangular structure is incorporated into the adobe walls of the patio and service road. Pipe canales and structural log vigas with sawn ends project from the western exterior wall. The comfort station, constructed in 1932, is scheduled for some changes that would allow wheelchair access.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE

The Museum/Visitor Center at Tumacacori National Monument is an unusual structure. Not only is it a fine example of Mission Revival architecture, but also it was constructed as an interpretive device so that visitors could better understand the architectural sense and history of that monument's prime resource: the Tumacacori Mission complex.

Although the ruins of Tumacacori Mission had been under federal protection since 1908, very little had been done in terms of development of the Monument. Rather than restore and reconstruct the mission complex on conjectural information, as the Works Progress Administration had done at Mission San Jose in San Antonio and other locations, the National Park Service historians, archeologists, and architects decided to preserve what remained of the adobe mission structures and instead put considerable effort into interpretation. This effort included the development of museum exhibits, but more importantly the construction of a museum that was an exhibit in itself.

Frank "Boss" Pinkley, the National Park Service head of the Southwestern Monuments, had definite ideas about the utilitarian aspects of the museum building. He wanted a low building that would not interfere with the historic mission complex and that was close to the parking lot so that visitors entered immediately. He wanted a pleasing facade, but nothing too ornate. He felt the building should be large enough for future expansion if required, but of a design that complemented the mission's architecture. He wanted reproductions of doors, windows, and floor and ceiling structure that were found in other Sonoran missions of the Kino chain. He also wanted a "view room" where visitors could look out at the mission complex, and he even set the axis of the museum building at a particular angle so that visitors could see that "knock-out" view he chose. [1]

Pinkley sent a team of park service men to Sonora, Mexico, in 1935 to record the remaining mission structures of the Kino chain and to study the architectural elements. Their task included studying the architectural structure of the missions to answer questions regarding stabilization or possible restoration, and gathering material for museum exhibits and architectural ideas for the museum itself. Members of the team were engineer Howard Tovrea, naturalist Robert Rose, official photographer George Grant, laboratory technician Arthur Woodward, and architects Leffler Miller and Scofield DeLong. Their visits to each of the missions was admittedly too short due to rebel uprisings, [2] but the information they gathered was an invaluable contribution to the history and archeology of the southwest. DeLong, the representative of the Branch of Plans and Design, became the principal designer of the museum building. He was ably assisted by other talented designers from that group including Dick Sutton, Charles D. Carter, and others, in addition to the vocal staff members from the Tumacacori and the Southwestern Monuments offices.

DeLong incorporated many of the elements he had seen in the Sonoran missions in his design for the museum building.

First, he chose construction materials similar to those used in the Sonoran missions. Walls were of sun-dried adobe bricks and cornices of fired brick. The shell motif in the reveal of the main entrance was patterned after the entrance to the mission church at Cocospera. The carved entrance doors were quite similar, although not exact duplicates, of those at San Ignacio. Other panelled doors in the museum building were similar to doors of Caborca. The carved corbels and beamed ceiling of the museum lobby were similar to the nave ceiling of Oquitoa. The museum lobby counter followed the design of the confessional at Oquitoa. The piers and arches of the museum portals were copied from those at Caborca. The groin-vault ceiling of the View Room was chosen because it was frequently used in Sonoran missions--at San Xavier, Tubutama, and in the baptistery at San Ignacio. The wooden grilles on the windows, the painted wainscotting, and the painted decoration of the groin vault in the View Room were also used as they had been in the historic missions. [3]

The construction of the building between 1937 and 1939 prompted visitors' questions about when services would be held in the new church, and what were they going to do with the national monument they were constructing. In a 1939 letter defending the new museum, one park service official noted that:

...Our architects and historians and museum men investigated the possibilities. One suggestion was to have the museum a string of adobe rooms along and around the parking area, but this would make a very sprawled out structure of NO PARTICULAR ARCHITECTURAL SIGNIFICANCE (his emphasis), for we must remember the architecture in the Jesuit and Franciscan periods was not unplastered adobe, but adobe walls neatly lime plastered and coated with bright colors...From all of this endeavor and thought there emerged the plan to make the museum and administration building at Tumacacori duplicate to the minutest detail the secular buildings which accompanied the Sonora-Arizona missions, always in the sane quadrangles with the churches. As you know, usually on one side of each mission is a quadrangle forming the living quarters of the priest; in front of the church is the patio, lined by the quarters of the neophytes, which sometimes developed into the town plaza if a town grew up around the mission. Tumacacori museum duplicated this "living and working quarters" style of architecture as of about 1800 A.D. [4]

Even the choice of plants for the museum garden was based on lists provided by historians such as Herbert Bolton from information garnered from mission records. [5] Although not exactly what Boss Pinkley had in mind--he preferred beans, squash, corn, and the like--the plants cultivated in the museum garden were all grown by the colonial mission padres [6]

The overall architectural concern in the design of the museum was not so much for the archeological fantasy that architect Mary Jane Colter had accomplished in her design of Hopi House at Grand Canyon. Rather, the park service architects and museum staff saw the Tumacacori Museum as a three-dimensional device that would give a sense of the shape and extent of the mission development and that could be used by the museum staff to show the visitors the historic construction techniques and materials. Their success remains evident in the well-designed structure.

The design for the Tumacacori Museum developed out of some contemporary architectural traditions. Pueblo Revival, Territorial Style, and Mission Revival architecture was popular throughout the west and southwest at the time. In addition the National Park Service Branch of Plans and Design under the direction of landscape architect Thomas Chalmers Vint had by that time developed its own design ethic of using onsite materials and primitive construction techniques to create an architecture in harmony with its setting. In large natural areas the architects designed rugged rustic buildings of stones and logs. In an area like Tumacacori the architects concentrated on cultural aspects and local building traditions, which in this instance stretched south to Mexico. The Tumacacori Museum was a part of those mainstreams of architectural thought.

An interesting side note is that Scofield DeLong began working for Tom Vint in the late 1920s as a temporary employee, during the formative years of park architectural thought. He was unable to get a civil service rating so he left the park service for a time and worked for Lewis P. Hobart, who was working on Grace Cathedral in San Francisco. The cathedral is a noteworthy building not so much for its impressive Gothic architecture but because of its poured-in-place concrete structure. Also of note are the cathedral's bronze doors which are casts of the Ghiberti doors on the Baptistery in Florence, Italy. One cannot help but notice a few parallels with the Tumacacori design. DeLong returned to work for the park service during the work relief programs of the 1930s. After World War II he worked for several years with the San Francisco architectural firm of Miller and Pfleuger, responsible for a number of progressive buildings in the Bay Area. [7]

FOOTNOTES

1 Southwestern Monuments Monthly Reports (September, 1936), p. 207.

2 Scofield DeLong and Leffler Miller, Architecture of the Sonora Missions: Sonora Expedition--October 12-29, 1935 (San Francisco: National Park Service, 1936), pp. 1-2.

3 Southwestern Monuments Monthly Report, supplement for February, 1938, pp. 175-176.

4 Dale S. King, "In Defense of the Tumacacori Museum Building," Southwestern Monuments Monthly Reports, supplement, (February, 1939), pp. 138-39.

5 Charles E. Peterson, Memorandum to Mr. Thomas C. Vint, March 6, 1930, Record Group 79. As early as 1930 Peterson was supplying this information to the landscape division. He noted that the list, which Bolton translated from the Kino papers from the archives in Mexico City, contained "few species of decorative value." Peterson also felt that although even in those early stages of development there was nothing compelling them to use historic plants that he also felt that it would be desirable to do so.

6 Pinkley and Custodian Louis Caywood both preferred a garden of the principal staples; the "landscape men," as Vint's group in the Branch of Plans and Design were known, preferred a garden that had historical accuracy and also was aesthetically appealing. After all, beans, corn, and squash were not much to look at in the off-season. As usual, the landscape men won out.

7 Telephone interview with William Carnes, retired NPS landscape architect, conducted by William Tweed, August 31, 1976; and David Gebhard, et al., A Guide to Architecture in San Francisco & Northern California (Santa Barbara: Peregrine Smith, 1973).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bleser, Nick, and Carmen Villa de Prezelski, Tumacacori National Monument Patio Garden Guide. Globe, Arizona: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, 1984.

DeLong, Scofield, and Leffler Miller, Architecture of the Sonora Missions: Sonora Expedition--October 12-29 1935. San Francisco: National Park Service, April, 1936.

Eckhart, George B., and James S. Griffith, Temples in the Wilderness: Spanish Churches of Northern Sonora. Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 1975.

Gebhard, David, et al., A Guide to Architecture in San Francisco & Northern California. Santa Barbara: Peregrine Smith, 1973.

Hosmer, Charles B. Preservation Comes of Age. Charlottesville: The Press of the University of Virginia for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1981.

National Archives Record Group 79 Records of the National Park Service.

National Park Service Western Regional Office files, including National Register files and List of Classified Structures field inventory reports.

Southwestern Monuments Monthly Reports, 1936-1940, various authors.

Tumacacori National Monument files including Bleser's abstracts from the Monthly Reports, and building data sheets.

BOUNDARIES

The boundary is shown as the dotted line on the enclosed sketch map (omitted from on-line edition). The boundary begins at a point 10 feet northwest of the northwest corner of the adobe wall, then proceeds south - southeast 700 feet (running parallel to and 10 feet west of the north portion of the adobe wall), then east 20 feet, then north to the south edge of the access road adobe wall, then east 150 feet, north 150 feet, west 150 feet, then northerly 450 feet running parallel to and 10 feet east of the adobe wall, then 20 feet west to the starting point.

PHOTOGRAPHS

(click on the above photographs for a more detailed view)

Top

Top

Last Modified: Mon, Feb 26 2001 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/harrison/harrison27.htm

![]()