Article

History, Preservation, and Power at El Morro National Monument: Toward a Self-Reflexive Interpretive Practice(1)

by Thomas H. Guthrie

In recent decades the National Park Service has begun to interpret a wider and more inclusive American history, one that has been not only triumphant but also painful, at least for some. At historic sites across the country, the perspectives of marginalized peoples and expressions of national shame increasingly coexist with (or, in some cases, altogether displace) more heroic stories of American glory. The interpretation of slavery at Civil War battlefields, Indian massacres, the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, the history of racism and the Civil Rights Movement, and women's history are a few examples. This more inclusive approach to historical interpretation has largely resulted from political pressure from underrepresented groups, trends in the discipline of history, and the rise of multiculturalism as a political philosophy.

In the context of this recent interest in more critical approaches to history, the park service must also begin to interpret its own place in the history of American national expansion and its own institutional power. It should also consider "deconstructivist" approaches in the social sciences that question interpretive authority and the relationship between knowledge and power. Such approaches call for an interpretation of interpretation, a self-reflexive and self-critical stance toward any object of study. The idea is that our own social position significantly affects our perspective as researchers and the kind of knowledge we produce. It follows, then, that knowledge production, far from being objective or neutral, is always embedded in relations of power since it involves the imposition of one perspective over others. Interpretation is particularly powerful when it comes with institutional backing, such as a book published by a professor at a prestigious university or an exhibit at a National Park Service visitor center. Recognizing these conditions, we have an intellectual, ethical, and political obligation to expose our own situated positions and the ways in which we have entered into and sustained power relations through the work of interpretation.

Through a critical reading of El Morro National Monument in western New Mexico, this essay explores the power of interpretation and the power that precedes interpretation—power rooted in assumptions about history and preservation that often seem common-sensical. I adopt a visitor's point of view, concentrating on the visitor center at El Morro, a two-mile trail that provides access to the monument's cultural resources, interactions with interpreters, and textual material available at the monument or on the park service website.(2) However, as a cultural anthropologist studying the politics of heritage preservation and interpretation in New Mexico, I have not been a typical visitor at El Morro. I approach monuments and historical sites with an academic eye. In addition, my scholarship has shaped and been shaped by my own political inclinations, particularly my critical view of colonialism and my tendency to sympathize with colonized peoples. The following analysis, then, does not represent neutral, disinterested social science (which I doubt exists, despite our best efforts at objectivity). Readers should consider the weaknesses and partiality of my argument. Someone who has actually worked for the National Park Service, someone with a different set of experiences, someone trained in a different field would surely perceive El Morro differently than I do. Because we are all able to see some things and not others, considering multiple perspectives is vital, and I offer the following analysis as one interpretation among many.

This leads me to a point of clarification. It is not my aim to criticize individuals who have worked at El Morro in the past or who work there now. The National Park Service is fortunate to have a dedicated and intelligent work force, from its central offices to its most far-flung units. I am consistently impressed with the park service employees and volunteers I meet across the country, including those I have met at El Morro. In fact, interpreters at El Morro have already initiated one major component of the changes I advocate in this article. However, I want to focus attention not on the individuals responsible for preservation and interpretation at El Morro but on the institutional context within which they have worked. I do this for several reasons. First, we are all part of larger social systems that influence us in countless ways, some of which we are unconscious of. People working at El Morro have not only faced bureaucratic limitations (such as tight budgets) but have also inherited (and sometimes confronted) institutionalized ways of thinking and doing their jobs. Second, our actions often have unintended effects of which we are unaware. The implicit message of American supremacy I hope to illuminate at El Morro is the subtle (even subliminal) effect of practices that have sedimented over time and therefore cannot simply be attributed to individuals and their deliberate efforts. Third, approaches to preservation and interpretation at El Morro have been typical within the national park system, both in technique and emphasis. This suggests that crediting or blaming individuals for what goes on there is less important than understanding larger institutional patterns. While my analysis focuses squarely on El Morro National Monument, it has implications for historical interpretation at other historical sites within the national park system.

It is also important to recognize, however, that individuals working together self-consciously can help to bring about beneficial change. Likewise, individual parks can serve as models for new interpretive approaches within the national park system. El Morro has already begun to demonstrate this potential by pursuing a more self-reflexive interpretative program. At the end of this article I will discuss what the park service has already accomplished; what a more self-critical interpretative practice might look like; and how such an approach can advance the historical, educational, and political mission of the National Park Service.

El Morro and Its Colonial Context

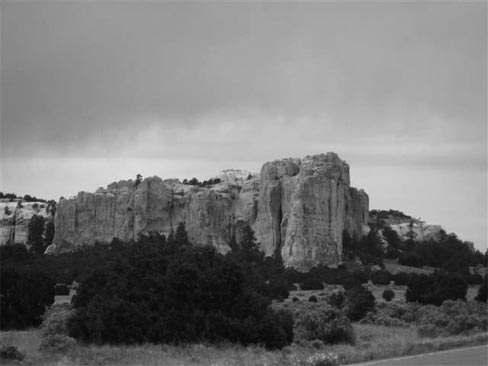

The focal point of El Morro National Monument, which is about a two-hour drive due west from Albuquerque, is a sandstone promontory ("el morro" means "the headland" or "the bluff" in Spanish). (Figure 1) At the foot of this bluff lies a deep pool of water that is fed by snowmelt and rain. (Figure 2) The only reliable source of water within a 30-mile radius, the pool attracted human beings to this place for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Ancestral Puebloans built stone dwellings on top of the bluff sometime in the late 1200s, which they moved away from in the 1300s. The remains of a village called A'ts'ina, which included more than 800 rooms, are still visible at the monument today. (Figure 3) The location of the pool ensured its continued importance over time. El Morro lay on the route between Acoma and Zuni Pueblos. Spaniards (who first wrote about the pool in 1583) stopped there on their way between the Rio Grande and the western Pueblos, and American settlers passed by the rock on their way west. Probably the most interesting feature of El Morro, though, is the rock itself, which Americans dubbed "Inscription Rock" because its base contains more than 2,000 petroglyphs and inscriptions. (Figure 4) Many of those Puebloan, Spanish, and American people who were attracted to this place because of its water left their mark on the rock.

|

Figure 1. El Morro, the bluff. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 2. The pool at the foot of the bluff. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 3. Exposed ruins of A'ts'ina on top of bluff. (Courtesy of the author.) |

|

Figure 4. Petroglyphs are among more than 2000 carvings on Inscription Rock. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Thanks to these inscriptions, El Morro rewards visitors with both spectacular scenery and fascinating history. Yet the way in which people have understood their place in history, that is, their historicity, and their relationship to this location has changed significantly since the 16th century. I believe that this transformation in historical consciousness, in which the National Park Service has played a key role, is particularly important because it tells us something about colonialism in New Mexico. For if Spaniards made history at El Morro, Anglo Americans have preserved it, and I want to suggest that both of these attitudes toward history represent an assertion of dominance in the region.

American colonialism in the Southwest does not have an end point in the past; it is not over yet and New Mexico is not "post-colonial" in any straightforward sense.(3) Political and economic conditions in the region provide ample evidence of this point. Native American and Hispanic communities tend to be impoverished and politically marginalized. Indians still have to negotiate their sovereignty with the federal government as "domestic dependent nations," while Hispanics continue to fight for land rights guaranteed under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848. Water rights remain highly contentious in the Southwest, and their adjudication requires courts to plumb the region's double colonial history to determine prior appropriation. In fact, everywhere we turn in the Southwest today we discover that the myth of "tricultural" harmony belies social, political, and economic hierarchies that remain characteristically (though complexly) colonial.

Although (or, as it turns out, precisely because) the National Park Service has focused its interpretative efforts at El Morro on Ancestral Puebloans, Spanish colonizers, and 19th-century American explorers, I will argue that the practice of preservation and interpretation at the monument has subtly reinforced American political power in the Southwest, relegating Indians and Hispanics to a past that is over and done with while making American ascendancy seem natural. Another way to put this would be in terms of visibility: while the park service has rendered earlier historical periods at El Morro imminently visible, its own significant interventions—informed by culturally specific values and assumptions—remain much less so, and thus relatively unassailable. In short, I want to suggest that Americans have asserted their dominance in part by taking themselves out of history and out of sight.

A critical interpretation of power at El Morro therefore requires an examination of two principles that guide much of the park service's work and that often go unquestioned: preservation and a form of multiculturalism that shifts attention from dominant to subordinate groups and that tends to be more celebratory than critical. The counterintuitive argument I want to make is that both principles have played a part in perpetuating American hegemony in the Southwest. If this is the case, I suspect it is not what employees at El Morro intended (in fact, I would not be surprised if most preservationists and advocates of multiculturalism found this claim repugnant). In order to substantiate this argument, I first need to contrast how Spaniards and Americans understood their place in history and asserted their presence at El Morro.(4) This historical detour will eventually lead me back to park service interpretation.

Spanish Colonization

When Spanish explorers first arrived in New Mexico in the 16th century they encountered Puebloan peoples whose ancestors had been living there for thousands of years. Juan de Oñate established the first Spanish colony in New Mexico in 1598, north of Santa Fe. Initial Spanish colonization was brutal; the Europeans were intolerant of Pueblo religious practices, and eventually, in 1680, the Pueblos united to expel the colonizers from their homeland. The Pueblo Revolt is one of the most important and successful indigenous uprisings in North American history, and Pueblo peoples today consider it an essential first step toward their cultural survival. However, the Spanish returned in 1692 under the leadership of Diego de Vargas to re-conquer the region.

Although El Morro and the western Pueblos were on the periphery of Spanish colonial activity in New Mexico (which centered on the Rio Grande), the rock became a record of Spanish colonization both before and after 1680. We think it was Oñate who made the first written inscription on the rock, upon his return from an expedition to the Gulf of California in 1605. (Figure 5) In translation, it reads, "There passed this way the Adelantado Don Juan de Oñate, from the discovering of the South Sea, on the 16th of April, 1605."(5) "Adelantado" was a title held by Spanish conquistadors who served the Crown as explorers, military commanders, and governors (the term implies going before or advancing). Various versions of the phrase "pasó por aquí" ("passed this way" or "passed by here"), which Oñate used, appear all over the rock.

|

Figure 5. Juan de Oñate inscription, 1605. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Numerous Spanish expeditions, both military and evangelical, passed by the rock in the 17th and 18th centuries and left inscriptions, many of which are self-aggrandizing. Some of the inscriptions are purely personal (names and dates). Others explicitly chronicle the work of colonization: exploration and the subjugation and missionization of Indians. Consider this anonymous inscription: "Captain-General of the Provinces of New Mexico for the King our Lord. He passed by here in returning from the pueblos of Zuni on the 29th of July of the year 1620, and he put them at peace at their petition, praying his favor as vassals of His Majesty, and anew they gave obedience. . .".(6) An inscription from 1632 marks the passage of a group of soldiers on their way to Zuni to avenge the death of a priest.(7) Diego de Vargas made a record of his reconquest: "Here was the General Don Diego de Vargas, who conquered for our Holy Faith, and for the Royal Crown, all the New Mexico, at his expense, Year of 1692."(8) To cite one last example: "Year of 1706 on the 26th of August passed this way Don Feliz Martínez Governor and Captain-General of this realm to the reduction and conquest of Moqui [Hopi] and... Reverend Father Friar Antonio Camargo Custodian and Vicar."(9)

It seems to me that these Spanish colonists etched their names and left messages in the rock not only to document their personal "place in history," so to speak, but also to leave a record of Spanish colonial activity across the region and, indeed, to stake Spain's claim to the region. Inscribing their names in this rock was thus similar to erecting a flag (or cross), leaving an indelible reminder that they had been there, that they had claimed this place.(10) Colonization involved not just acts of exploration and conquest, suppression and domination, but also a wide array of symbolic assertions of power. For instance, historical geographer Richard Francaviglia has noted the importance of map making in the Spanish colonization of the Southwest, highlighting the relationship between representation and power.(11) As Spanish explorers, conquistadors, soldiers, and priests literally made history at El Morro, they asserted their authority over both time and space. When Dan Murphy (in a booklet published by the Western National Parks Association and sold in the El Morro gift shop) calls the rock "one of the significant documents of Southwestern history" and "the Southwest's most permanent history book," he implicitly confirms the relationship among writing, history making, and colonial power in the Southwest. Describing El Morro as the place "where history began in America" has a similar effect.(12)

American Colonization

The year 1744 marks the last Spanish-language inscription at El Morro, and there are no inscriptions clearly from the Mexican period. Mexico declared its independence from Spain in 1821, and regional hostilities between Mexico and the United States culminated in 1846 with the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo brought an end to the war in 1848 and the cession of a vast territory including New Mexico to the United States. Thus began the second colonization of New Mexico. The coming of the railroad in the 1880s spurred Anglo settlement of the Southwest, and land ownership and water rights quickly became contentious. Indians were attacked, dispossessed of their lands, and subjected to decades of forced assimilation. Meanwhile, Spanish and Mexican land grants were largely broken up, leaving Hispanic communities disenfranchised, with limited political and economic power. Both Indians and Hispanics have accommodated, adapted to, and resisted American authority in complex ways.

In the 19th century, the Americans who passed by El Morro tended to be part of either military campaigns against Indians, survey teams charting possible rail routes and the position of the new national border, or emigrant trains headed west. The fact that it is often difficult to distinguish scientific expeditions from military campaigns, since the army employed surveyors, geographers, artists, and other specialists to study and document the newly acquired territory, is a perfect example of the relationship between knowledge production and power. Inscriptions at El Morro bear testament to each of these pursuits, all of which were facets of American national expansion. The inscriptions thus provide a document of American colonial activity in the region, just as the Spanish inscriptions did.(13) So throughout the 19th century we see Americans recording their presence and asserting their authority over the Southwest in precisely the same way as their predecessors had.

A sense of racial superiority helped to justify American control of the Southwest. For example, visitors to El Morro today learn about Edward F. Beale, who supervised an experiment to see whether camels could perform well in the desert Southwest. (Beale fought in the Mexican-American War and became the superintendent of Indian affairs in California and Nevada.) The caravan passed through El Morro in 1857, and upon his return from California in 1858, Beale visited Inscription Rock again and made this report:(14)

Inscriptions, names, and hieroglyphics cover the base, and among the names are those of the adventurous and brave Spaniards who first penetrated and explored this country, with dates as far back as 1620. The race has long ago passed away, and left no representative of Spanish blood behind them. Those with us looked with listless indifference at the names of the great men of their nation, and who made it famous centuries ago, cut by themselves upon this rock, and turned off to take charge of the mules, which is about all even the best of them are fit for. |

Beale's glorification of Spanish conquistadors was typical of this period. But note how he, in an apparent contradiction, simultaneously erased people of Spanish descent from the New Mexican landscape and denigrated those who remained. (Perhaps Beale intended to contrast "noble" Spaniards and "degenerate" Mexicans, which would also have been typical.) The way in which Beale relegated Hispanics to the past and portrayed them as incapable of appreciating the historical significance of the rock foreshadowed future interpretation at El Morro, as we will see. Notably, the visitor center at the monument today highlights Beale's interesting camel experiment (which ultimately came to nothing) but omits his blatant racism.

"Here Were Indeed Inscriptions of Interest"

Despite similarities between Spanish and American colonialism in the Southwest, from the very beginning there was an important difference in the way Americans thought about history at El Morro. In fact, I want to suggest that the first English speakers to visit the rock inaugurated a new way of establishing colonial authority in New Mexico. In 1849, just a year after the United States officially acquired the territory, an army expedition set out from Santa Fe to make a treaty with the Navajo at Canyon de Chelly and to bring them under the jurisdiction and control of the United States. Lieutenant James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, and Richard Kern, an artist from Philadelphia, were part of the expedition, and on their way back to Santa Fe they made a detour past El Morro.(15) The reason for the detour, significantly, was not the pool of water that had attracted visitors in centuries past but the inscriptions on the rock, which their guide promised were worth seeing.(16) Simpson was not disappointed when he reached the rock:(17)

The fact then being certain that here were indeed inscriptions of interest, if not of value, one of them dating as far back as 1606, all of them very ancient, and several of them very deeply as well as beautifully engraven, I gave directions for a halt—Bird [Simpson's servant] at once proceeding to get up a meal, and Mr. Kern and myself to the work of making facsimiles of the inscriptions. |

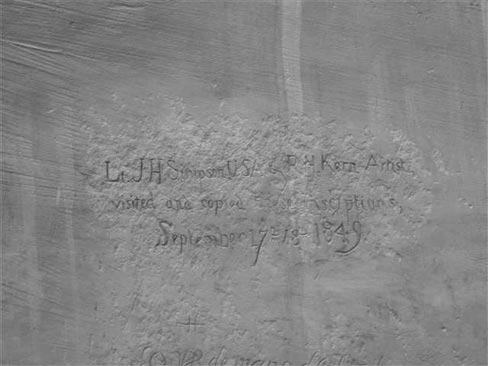

The men spent the next day completing their documentation of the inscriptions and then, before departing, added their own inscription to the rock: "LT. J.H. Simpson U.S.A. and R. H. Kern, Artist, visited and copied these insc[r]iptions, September 17-18 1849." (Figure 6)

|

Figure 6. Simpson and Kern inscription, 1849. (Courtesy of the author.) |

This was likely the first English-language inscription on the rock, and it represents a transition in historical sensibility. Simpson and Kern left a record of their presence just as previous travelers had, but they also made a record of the previous inscriptions, which they considered interesting. In fact, the message that they left pointed to the record that they made. Their participation in history was thus subordinate to their documentation of history. And in documenting the Spanish past at El Morro, they simultaneously marked the beginning of the American present.

El Morro began to fall off the map when the Santa Fe Railroad bypassed it in the 1880s. No longer a significant oasis for cross-country travelers, it soon entered its modern historical period. As Americans continued to document and publish records of the inscriptions(18) the rock's reputation as a historic site grew. In order to understand how Simpson and Kern's documentarian impulse and sense of history may have represented a new, implicit expression of colonial dominance we must look to the 20th century, when the National Park Service completed the transformation of El Morro's meaning and historicity. In the next section I return to the issue of interpretation, suggesting that, until recently, interpretive patterns at El Morro have perpetuated and expanded assumptions about American ascendancy in the Southwest.

Fixing History at the National Monument

The practice of preservation and interpretation at El Morro has, for more than a century now, largely confirmed that New Mexico's Pueblo, Spanish, and early American inhabitants are historical while treating 20th-century Americans as if they were beyond history, simply modern. This interpretive pattern effectively normalizes the political presence of Americans in the Southwest by deflecting critical attention from Anglo preservationists. I doubt this interpretive effect is intentional, and there is certainly no explicit celebration of American modernity at El Morro. Nevertheless, the message visitors encounter has until very recently been remarkably consistent. (The next section discusses notable updates at El Morro that could inspire other units in the park system to change the ways they approach interpretation.)

First consider an inaugural policy. El Morro was one of four national monuments established in 1906 after the passage of the Antiquities Act.(19) From that point on, the Federal Government prohibited any new inscriptions on the rock, although the policy was not enforced until the 1920s. Early park superintendents worked both to preserve early inscriptions and to erase those post-dating the monument designation, demonstrating a self-conscious, bureaucratic attempt to manage the site's historical meaning and period of significance. Specifically, these new policies and procedures effectively fixed the meaning of the monument as a historical record. As El Morro became an officially designated historic site, it was taken out of history, its historical significance fixed in the past.(20) Whereas Spanish explorers and missionaries made their mark on the rock in a sort of living, evolving history that had no stated ending point, representatives of the American government prohibited this practice, although the park service has extensively inscribed the monument in other ways.(21)

Interpretation at the monument visitor center has tended to entrench this understanding of history. The NPS unigrid brochure and a Western National Parks Association booklet(22) both summarize El Morro's history up to the 1880s. The exhibit in the monument visitor center, created in the 1960s, does not even make it that far. It covers the Puebloan occupation of the bluff in the 13th century, Spanish colonization, the Pueblo Revolt, the reconquest, American colonization, and Beale's camel expedition. The final panel discusses 19th-century military campaigns against the Navajo and Apache, concluding, "in time all of the tribes were conquered."(23) A video ends with the establishment of the monument in 1906, when further inscriptions were prohibited. And Slater includes in his book little more than a paragraph on the history of El Morro after the designation.(24) All of these sources leave visitors with the impression that the history of El Morro ended when it became a national monument, if not several decades before.

This historical bracketing is represented differently in a small, temporary exhibit titled "Let the Rock Tell the Story." The display represents five "eras" of El Morro's past stratigraphically, through horizontal illustrations of what El Morro might have looked like. The top layer, "El Morro in the Present Era" includes this caption: "Today is a time of preservation, protection and understanding. The beauty of the rock stands before us and is forever changing." Photographs of wildlife and park service employees working on the monument illustrate this period. The second layer, "El Morro in the Cultural Era," represents the monument from Puebloan occupation through the 1800s with a montage drawing of a pot, conquistador's helmet, and emigrant's trunk, each in front of the bluff. The three bottom layers describe the geology and paleontology of El Morro in the Tertiary, Cretaceous, and Jurassic eras (from 65 to 170 million years ago).

What strikes me about this exhibit is that it contrasts "the present era" with "the cultural era." Here we find a visual representation of the idea that not only is our current "time of preservation, protection and understanding" beyond history, but it is also beyond culture.(25) This is a well-worn understanding of (colonial) modernity: modern Europeans and Euro-Americans, unlike "traditional" societies and earlier Western societies, are no longer defined or bound by culture or time. This display in the visitor center therefore illustrates not a curious word choice but a much broader cultural pattern, even if it was intended to be simply an exhibit about geology.

This cultural pattern is racialized in the Southwest, where the idea of "cultureless" Anglos relates to the invisibility and privilege of whiteness.(26) In New Mexico, tourists often consider Native Americans (and, to a lesser extent, Hispanics) to be colorful and interesting. They stand out, especially in comparison to Anglos, who are generally assumed to lack ethnicity. The whiteness of Anglo Americans helps to account for their invisibility in tourist imagery. Another way to make this point would be to say that Indians and Hispanics are marked by their difference while Anglos are unmarked. Marking in this sense represents an assertion of power, because the unmarked category remains the standard or norm (that is, Anglos are just normal, modern) against which others are measured (the others are different, strange).

The problem with these interpretive elements, as I see it, is not simply that they are incomplete, but that they effectively perpetuate American colonial power in the Southwest, albeit implicitly and inadvertently. This is despite the fact, or, rather, because of the fact, that the park service has tended to lift up New Mexico's Indian, Spanish, and early American history at the monument while demurring from interpreting its modern American history. This historical bracketing has two effects. First, New Mexico's Indian, Hispanic, and territorial "periods" are firmly fixed in the past. Their historical significance has been confirmed, but they are also relegated to history. They are over and done with, literally set in stone and in history books that have been closed. There is hardly any visual or textual acknowledgement at the monument today that Native Americans and Hispanics even survived into the 20th century (a serious shortcoming that the park service has made progress in correcting at other parks). Second, modern American history and culture, characterized by a preservationist ethic, remain living and vibrant, not quite historical at all. They are associated with New Mexico's present and future. (Even references to the Puebloan, Spanish, Mexican, and American "periods" in the Southwest reinforce this sequential, progressivist narrative.) The American vantage point is taken for granted and naturalized at the monument, where American preservationists, having stepped out of the scene, remain hidden and therefore beyond critique.

It may seem like this truncated historical narrative and the "invisible" power I am associating with it are fairly innocuous, especially in comparison to the blatant racism, violent domination, and ethnocentrism of the 19th century. Yet the fact that this interpretive pattern comes on the heels of American conquest is significant. A brief consideration of continuity and change in the history of colonialism in the Southwest may therefore help to clarify my argument. El Morro illustrates a trend in the history of European and Euro-American colonialism evident in many parts of the world. Over time, we often see a shift from colonial domination that is based on coercion and overt acts of violence to colonial domination based on consent and culturally sustained inequality. Scholars often refer to this second form of power, which operates through culture and seemingly natural social arrangements, as hegemony. One characteristic of the transition from coercive to hegemonic colonialism is a changing relationship between visibility and power, which I believe the history of El Morro illustrates. If early colonizers in New Mexico endeavored to make themselves and their authority visible and to erase the presence of the colonized (symbolically if not literally), later colonizers attempted the opposite. Both techniques represent an assertion of power, though in different ways.(27) El Morro does therefore demonstrate significant change over time, but it also reveals startling continuity: overt and hegemonic forms of domination differ, but they are both forms of domination.

The subtlety of this power-through-preservation makes it difficult to perceive and thus to criticize. And the fact that this new form of colonial entrenchment is often unintentional or counter-intentional makes it even harder to believe. Yet often our actions and the cultural patterns we unconsciously perpetuate have unintended consequences of which we are unaware. It is precisely the subliminal, invisible, unintentional, and counterintuitive nature of the power I am attempting to illuminate that makes it significant and worth studying.

Toward a Self-Reflexive Interpretive Practice

So what policies and practices would I recommend instead? First of all, I am not suggesting that the park service repeal its prohibition of new inscriptions. Doing so might revive a more vibrant, living kind of history at the monument, a history in which we participate as active agents, an open-ended history that is not yet finished or determined. Visitors might even glean a more authentic understanding of the experiences of those who passed by this very same place long ago.(28) And who is to say that the name of someone who died 300 years ago is more important than my name, or my child's? Allowing new inscriptions would certainly result in the loss of older ones (the monument receives 35,000 visitors a year), but such loss happened in the past, is inevitable in the future, and could be mitigated through documentation.

Still, the prohibition makes sense to me, and I am glad that we can still see all those engravings from the past. Not only are the inscriptions interesting, they can teach us something about people who came before us and the history of the Southwest. Happily, the park service has provided two boulders outside of the visitor center and a sign that reads, "Carve your initials on this typical piece of local sandstone, if you must—but please remember: it is against the law to carve anything on Inscription Rock itself!"(29) (Figure 7) Visitors can also "inscribe" their names in the monument's registry.

|

Figure 7. Boulders available for inscription outside the visitor center. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Rather, I urge the NPS to continue in the direction it has charted in recent years, interpreting the monument's own history, historicizing preservation, and moving toward self-exposure. The first logical step in this process, already underway at El Morro, is to do away with the historical bracketing I described above and to include the management of the park in the historical narrative conveyed to visitors. This more inclusive interpretation does more than bring the monument's history "up to date." More fundamentally, it conveys to visitors that Anglo preservationists are just as embedded in culture and history as were Ancestral Puebloans, Spanish colonists, and early American explorers. Interpreting 20th-century cultural history means that preservationists at El Morro no longer occupy a privileged position above (or outside of) culture and history, the "present era" of (nothing but) protection and understanding.

The park service has recently made great strides in interpreting the history of the monument and providing visitors with a more complete understanding of this place. A temporary display in the visitor center developed for the centenary of the monument ("El Morro National Monument: 1906-2006") included 19 black-and-white and color photographs of the monument since its designation (including pictures of people working at the monument), copies of two documents relating to the monument's establishment and administration, and four laminated pages with text.(30) Two of these pages described the creation of the monument in 1906 and what it was like to live and work at El Morro in the early 1900s. A third discussed cultural resource management:

Early efforts to protect inscriptions from the elements of nature included covering the carvings with paraffin, chiseling grooves to reroute water flows and darkening and deepening inscriptions with hard pencils to offset the erosion that was occurring. These first, well intended though intrusive attempts to preserve the inscriptions ended in the 1930s. However, erosion and weathering continue to pose the ultimate challenge to the National Park Service mission of preserving cultural resources in perpetuity while allowing natural processes to occur. |

The sign went on to discuss the treatment of the ruins on top of the bluff. The fourth page explained several major alterations to the pool in the 1920s: "The first custodian enlarged the catchment basin to provide more water for area ranchers and their stock, and erected a dam which would help retain water otherwise lost in runoff."(31)

When I returned to El Morro in 2008 this display had been broken up.(32) The sign about the pool had been moved to above the water fountain, and a kiosk near the front of the visitor center featured displays on technical preservation problems, the history of the monument's visitor centers, life at the monument in the early 1900s and preservation efforts in the 1920s (both from the centennial display), and improvements to the monument during the New Deal. Parts of the centenary display had also been mounted in the campground.

New wayside exhibits installed during the summer of 2008 extend this interpretation of the monument's history. (Figure 8) Four of the eight new signs focus exclusively on park history and management (including the topics noted above) and a fifth mentions them. And a new walking guide for the Inscription Rock trail mentions changes to the pool in the 1920s and 1940s, early "well-intentioned but intrusive" preservation attempts, and the erasure of inscriptions.(33)

|

Figure 8. A wayside exhibit on recent methods of preserving El Morro's history. (Courtesy of the National Park Service.) |

Perhaps even more importantly, interpretive rangers talk to visitors about the history of the monument (and have been doing so since at least the early 1990s). On the two-hour guided hike I went on in 2008, the ranger began by reminding us that Inscription Rock was a "historical document" and not a "living document" and that new inscriptions were strictly prohibited. (She disgustedly told us about and later pointed out a very recent inscription—"Alex + Bree = BFF"—that she said she would gladly erase herself.) But her well-informed narrative frequently turned to the 20th century (the construction of the dam, New Deal projects, early and current preservation efforts, the paving of the highway, controlled burns, visitor antics, etc.). When we got to the top of the bluff, another ranger (who happened to be Zuni) told us about ongoing work on the ruins.(34) Neither ranger ever came close to suggesting that the history of the monument was over. Quite the contrary, the 20th and 21st centuries were alive with activity in their accounts.

Finally, the park service website includes several pages on preservation challenges at El Morro,(35) although most emphasize technical problems rather than park history. One page gives a brief history of park service buildings at the monument, concluding, "The 1939 sandstone residence now serves as the administrative offices for El Morro. Today it is, as well as the Mission 66 visitor center, as much a part of El Morro's history as the inscriptions themselves."(36)

In my view the new visitor center exhibits, the new wayside signs, oral interpretation at the monument, and the park service's website significantly enrich interpretation at El Morro in that they historicize and humanize the monument's early custodians (who made some decisions that seem regrettable in hindsight) and call attention to current management challenges. As I suggested above, these new interpretative initiatives do much more than update or supplement a historical narrative. More importantly, they break open a historical barrier that has indirectly supported the authority and presence of the Federal Government in the Southwest for decades (even if they were not created for this purpose). They also demonstrate that the park service can effectively and successfully pursue more self-reflexive interpretation.

As with any work in progress, there is still room for improvement. The effect of the older interpretive elements I discussed in the previous section (all of which are still in use) will not be easy to overcome. Compared to the larger and more visible permanent exhibit in the visitor center that ends with the conquest of the Navajo and Apache, the temporary displays are marginal. In addition, not all visitors will spend time talking to interpreters, which underscores the significance of textual and visual interpretation.

It will, of course, take time and money to continue to improve interpretation at the monument. The park service has already taken, and surely will continue to take, interim steps in its interpretive program. For example, while waiting for funding for a new exhibit, it may be possible to supplement an outmoded display with an interpretation of interpretation. Small and inexpensively produced signs posted at the beginning, at the end, or throughout the exhibit could inform visitors about the age of the display, comment on particularly problematic segments, or provide alternative perspectives. Historicizing and deconstructing the authority of park service interpretation would promote critical thinking and may even encourage visitors to consider what it takes to support park service interpretation.

I believe the park service must continue to expand its interpretation of monument history. Consider, for example, Slater's commentary on the erasure of inscriptions in the 1920s:(37)

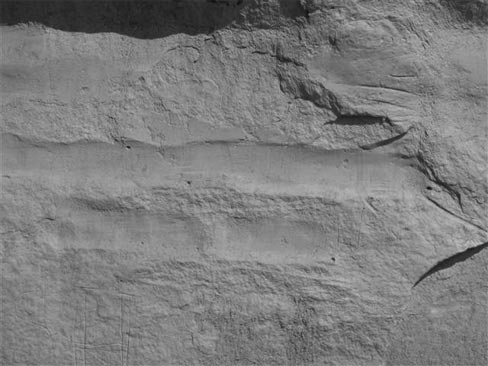

Ironically enough, the greatest single act of damage to the rock took place after the establishment of the Monument. About 1924 an attempt was made to cleanse the rock of countless worthless signatures by rubbing them out with sandstone. In the course of this ill-advised project many valuable inscriptions were erased, and the beautiful sandstone was so disfigured as to draw questions, from the most casual visitor, as to what happened. |

Erased sections are indeed evident all over the rock today (Figure 9), and in my experience the park service acknowledges and explains them(38) but does not interpret the process of erasure or treat the erased sections as an educational opportunity. The point is not simply to disclose embarrassing missteps but to encourage visitors to think critically about preservation, historical sites, and park management (which is, after all, funded by taxpayers). Nor is it sufficient to interpret the early history of the monument but to leave more recent practices untouched (which might actually shield the current administration from scrutiny).

|

Figure 9. Erased inscriptions. (Courtesy of the author.) |

I particularly like the open-ended questions that conclude a two-page brochure on preservation challenges at El Morro available on the park service web site: "We must ask ourselves what treatments are acceptable and how far we will go to delay the inevitable. Cover the rock wall with glass? Remove the inscriptions and place them in a museum? Or should we allow nature to take its course?"(39) These are excellent questions, difficult to answer and bound to get visitors thinking. In my view they do as much as, if not more than, exhibits that inform visitors what the park service is already doing in terms of preservation.

In fact, I would like to see the park service pursue this kind of open-ended interpretation even further, focusing critical attention on not just the techniques but also the philosophy of preservation. While this approach would be appropriate at any historic site, it is especially relevant at El Morro since it would provide visitors with a more complete understanding of the rock's history. Preservation and the prohibition of further inscriptions were, after all, historical. Indeed, the 1906 prohibition seemingly points to a radically new way of thinking about this place and its history, yet today it is mentioned matter-of-factly, if at all, in descriptions of the monument. If the park service already interprets the cultural significance of the rock for Pueblo Indians and Spanish colonists, why not interpret its significance for 20th-century Anglos as well? Each of these groups has had a different relationship to the rock, and contrasting the three perspectives would be fascinating.

I suspect that the only reason preservation has not been held up for inspection is because it has been taken as a rational, natural, and self-evident stance, beyond history. Yet we know now that historic preservation is not a natural response to the world but one that has arisen in particular cultural and historical circumstances.(40) This peculiar cultural response to this place deserves interpretation simply because it is a part of history, even if we still consider ourselves to be living in a "time of preservation."

The park service should minimally explain and interpret preservation at El Morro to visitors. Why preserve this site? The answer to this question may not be as obvious as it seems, and the park service should be able to provide some specific answers. If interpreters begin to treat preservation as a cultural rather than natural response to the rock, then they will need to justify preservation to visitors. Making an explicit argument for preservation will help the agency spread the preservation ethic since visitors will become able to make sense of preservation rather than simply receiving it as a passed-down mandate. Yet the more the park service denaturalizes and justifies preservation, the more some visitors may begin to question it. This possibility may seem scary or even threatening to the park service, but if preservation is a good idea it should be able to withstand scrutiny. Furthermore, I submit that a thinking visitor is always a better visitor.(41) Visitors might begin to call into question their own assumptions, and those of the government, about "history" and the government's management of historic sites. They would certainly be better informed and better able to appreciate this place, its ongoing history, and the work of the National Park Service.

Advantages of Self-Critical Interpretation

In conclusion, let me summarize what I consider to be three advantages for the park service of self-critical or self-reflexive interpretation at El Morro and beyond. First, interpreting the more recent past (in the case of El Morro, its history since 1906) will result in a more complete historical understanding. Much of the historical interpretation at El Morro currently may leave visitors with the impression that the site's history ended when it became a national monument, which of course is not true. National Park Service management, itself an unfolding process, is part of, not beyond, history and thus deserves interpretation too. At El Morro this potential is particularly intriguing because of parallels and contrasts between Spanish and American colonization.

Second, self-reflexive interpretation serves the park service's mission as an educational institution. This mission is dear to me as a teacher. In the classroom, I believe that my most important task is not to provide information to my students but to encourage them to think critically about the world in which they live (especially about present-day social arrangements). Too often students forget content (sometimes as soon as the exam is over!), but if we teach them how to think, what kind of questions to ask, and how to look beneath the surface of complex situations, they can use these skills throughout their lives. The National Park Service has the opportunity to get visitors thinking and to challenge their preconceived assumptions and values at every single unit in the country, which may be more important than presenting them with straightforward historical narratives (history is rarely straightforward anyway) or cultivating an uncritical patriotism. The agency is already doing this to a certain extent, of course, but interpreters and educators can more consistently emphasize critical reflection.

Prioritizing critical thinking over the acquisition of information may also help to alleviate concerns that limited time and space make it unrealistic to expand historical interpretation. Discussing a monument's recent history even briefly will likely mean that interpreters have less time to talk about its "core" historical significance, the reason it was designated a monument in the first place. Yet as I have argued in this article, it may be appropriate to rethink what makes individual parks and monuments significant. Their significance may lie as much in the present as in the past, and it surely evolves over time. At El Morro, I believe that 20th-century American colonialism is no less significant than the history of Puebloan occupation, Spanish colonization, or 19th-century American exploration.

Third, there are also civic benefits to self-critical interpretation. Encouraging visitors to think critically about the National Park Service itself would lay the foundation for a more democratic and just public history. Keeping in mind that the park service has been a part of American history reminds us that it is and has been an agent of the Federal Government, for better and for worse. While the park service has not always represented all Americans, as a federal agency it must do so today. The park service has already begun to acknowledge the contributions and perspectives of minority groups in the United States, a process that must continue. But the agency has not adequately owned up to its own role in the oppression and marginalization of some of those groups in the past and present. The relocation of Native Americans and others in order to create parks and their subsequent exclusion from these "wilderness" areas are well-known examples of this colonial history.(42) Interpreting the history of the National Park Service is particularly timely as the agency's 2016 centennial approaches.

The park service has also been responsible for more subtle, often unintentional, forms of domination. Historicizing and revealing the politics of park management thus has the potential to disrupt Eurocentric policies and practices and to make space for all Americans within the national park system. The self-critique I am proposing might therefore help the park service to broaden its visitorship. At El Morro, imagine a Hispanic visitor encountering a federal agency that is willing to tell the story not only of brave conquistadors and intrepid camel-drivers but also of American racism and a set of policies and practices that implicitly elevated the position of Anglo Americans in the Southwest. (Is anger ever an appropriate emotion at national monuments?) Imagine a Native American encountering a narrative that subjects 20th-century Anglos to the same scrutiny as other groups. This self-reflexive interpretation would no longer implicitly privilege Anglos as the representatives of a triumphant modernity while relegating Indians and Hispanics to the past. So long as interpretation at El Morro perpetuates the assumption that Anglo preservationists are beyond culture and history, and so long as Anglos maintain the privilege of invisibility, the monument will continue to marginalize visitors who do not identify with the dominant group.

Multiculturalists committed to highlighting the lives, experiences, and perspectives of marginalized groups might object to this suggestion to focus more attention on powerful white people. Ironically, however, spending more time talking about 20th-century Anglo Americans at El Morro could help to equalize the various groups associated with this place. My point is not that the park service is wrong to interpret the history of Puebloan and Spanish peoples at El Morro (which of course it should) but that it must no longer implicitly treat 20th-century Anglos as cultureless, normative, and simply "modern." For too long this interpretive pattern has confirmed the association of Indians and Hispanics with New Mexico's past and Anglos with its present and future. A corollary to this point is that the park service must also make it clear that Native Americans and Hispanics did not die out but inhabit the Southwest in the 21st century as modern-day peoples.

American democracy is built upon the ability of the people to question their government, and a federal agency that actually encourages, rather than avoids, this questioning is truly inspirational. National parks and monuments reach their full potential when they become forums where Americans can safely and respectfully encounter and talk about difficult and divisive issues. El Morro National Monument certainly has the potential to foster this kind of civic engagement.

El Morro is a true gem within the national park system, one definitely worth caring about. If older interpretive practices at the monument—typical of National Park Service interpretation in their emphasis—effectively extend the history of American colonialism in the Southwest, the advancement of a self-reflexive interpretive program might enrich historical understanding, promote education, and nurture democracy and equality on federal land.

About the Author

Thomas H. Guthrie is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina. He may be reached at tguthrie@guilford.edu.

Notes

1. I gratefully acknowledge the thoughtful comments of Damon Akins, Barbara Little, Dwight Pitcaithley, Dick Sellars, Cathy Stanton, and two anonymous reviewers on previous drafts of this article. I extend special thanks to Kayci Cook Collins (Superintendent of El Malpais National Monument and El Morro National Monument) and Leslie DeLong (Chief of Visitor Services and Facilities at El Malpais and El Morro), who not only provided helpful feedback but were gracious, friendly, and supportive in the face of critique.

2. I have visited El Morro four times since 2001, each time paying close attention to the interpretive narrative conveyed to visitors. During each visit I talked to rangers and hiked the two-mile trail, following along in the guide book available to visitors that interprets points along the way (on my most recent visit I hiked the trail in a group with a ranger). This trail, the visitor center, a picnic area, and a campground round out visitor opportunities at the 1,279-acre monument. I have also talked about interpretation with the monument's superintendent and the chief of visitor services. This investigation is part of a larger and ongoing research project on the politics of heritage preservation and interpretation in northern New Mexico, with a focus on projects involving the National Park Service. See Thomas H. Guthrie, Recognizing New Mexico: Heritage Development and Cultural Politics in the Land of Enchantment (University of Chicago, Ph.D. dissertation, 2005).

3. What "post-colonial" means and how that term might apply to settler colonies such as the United States are both theoretically debatable. See Stuart Hall, "When Was 'The Post-Colonial'? Thinking at the Limit," pp. 242-260 in The Post-Colonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons, ed. Iain Chambers and Lidia Curti (London: Routledge, 1996).

4. The significance of El Morro for ancient and modern Pueblo peoples, as well as how these groups transformed the rock, is an important topic that deserves careful consideration, but my analysis begins with Spanish colonization.

5. John M. Slater, El Morro: Inscription Rock New Mexico: The Rock Itself, the Inscriptions Thereon, and the Travelers Who Made Them (Los Angeles: Plantin Press, 1961), 7.

6. Slater, 8.

7. Slater, 10.

8. Slater, 13.

9. Slater, 18.

10. All societies inscribe their presence on their surroundings, though in very different ways, as will become clear once we consider NPS activity in the 20th century.

11. Richard Francaviglia, "Elusive Land: Changing Geographic Images of the Southwest," pp. 8-39 in Essays on the Changing Images of the Southwest, ed. Richard Francaviglia and David Narrett (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1994), 13-16.

12. Dan Murphy, El Morro National Monument (Tucson: Western National Parks Association, 2003), 3, 11; Kit Carson, New Mexico's Inscription Rock: "Where History Began in America!" (New York: Vantage Press, 1967). Like Murphy, Kit Carson (not the famous frontiersman but perhaps his grandson) conceived of Inscription Rock as a historical text. Carson, 14, explained that all those who inscribed their names on the rock "left a lasting registration which has resulted in colorful history, almost a paragraph—topic by topic—of America. The unintentional picture they left in passing has become a history as legend in time becomes lines in the same volume...." Yet the "history" that most commentators associate with El Morro—almost always a chronological, linear story that begins with Native Americans, proceeds through Spanish colonization, and ends with Anglo Americans—contrasts with the rock itself. The rock does not contain a linear, chronological record. Rather, the inscriptions are all mixed up, even superimposed on one another. Furthermore, there are numerous examples of annotations and deletions (see Slater, 8, 20), evidence that if the rock is a historical record, it has been edited and contested over time. This jumbled record is clear in the guide books that highlight points of interest along the trail at the foot of the rock (see El Morro Trails: El Morro National Monument, New Mexico [N.P.: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, n.d. (1998 printing)]; Abby Mogollón, Guide to the Inscription Trail: El Morro National Monument, New Mexico [N.P.: Western National Parks Association, 2008]; Slater, 53-75), but most of the narratives visitors encounter rearrange the inscriptions to produce a straightforward chronology. My point here is that "history" (a story we tell about the past) is an interpretation, not something found chiseled in stone. Conflating the work of interpretation with its object (as Murphy and Carson do) naturalizes "history" and conceals the partiality of interpretation. After all, alternative histories could be gleaned from the rock if the inscriptions were left jumbled. Perhaps El Morro conveys a story not of linear progression but of violence (people scraping their names over other people's marks), ephemerality, or simply disorder.

13. John Slater notes that the name of Kit Carson (the famous frontiersman and Indian fighter) once graced the rock. Although it was erased, "Carson, being a good soldier, had a reserve—an inscription on the walls of Keams Canyon in the Navaho country" (See Slater, 45). I heard a ranger at El Morro say that it was a former Navajo NPS employee who had erased Carson's inscription, presumably as a political statement.

14. Edward F. Beale, "Wagon Road from Fort Defiance to the Colorado River," Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting the Report of the Superintendent of the Wagon Road from Fort Defiance to the Colorado River. U.S. 35th Congress, 1st session, H. Exec. Doc. 124, 1858, 85.

15. James H. Simpson, Navaho Expedition: Journal of a Military Reconnaissance from Santa Fe, New Mexico to the Navaho Country Made in 1849 by Lieutenant James H. Simpson. Edited and annotated by Frank McNitt (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964 [1850]), 125-137.

16. Simpson's party spent an entire afternoon copying the inscriptions before setting off to inspect the ruins on top of the bluff. It was only then that the explorers found, "canopied by some magnificent rocks and shaded by a few pine trees, the whole forming an exquisite picture, ...a cool and capacious spring—an accessory not more grateful to the lover of the beautiful than refreshing to the way-worn traveler" (see Simpson, 128). Simpson's journal makes it clear that the discovery of this "accessory," as significant for its aesthetic as its practical value, was of secondary interest.

17. Simpson, 127.

18. Slater, 38, 48, 49.

19. Land acquisition and the control of resources in the name of preservation or conservation (authorized by the Antiquities Act and other laws) were a more direct form of American colonial domination than the interpretive practices I discuss here but are beyond the scope of this article.

20. See Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 149-176, who has shown that heritage is always constructed in the present through processes of exhibition and display that entail the kind of fossilization evident at El Morro (see also Guthrie, 104-60). See Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (New York: Schocken Books, 1999 [1976]), 43-45, who has elaborated a complementary theory of tourist sites, arguing that they must be framed and decontextualized in order to be perceived as attractions.

21. Signs dot the landscape of the monument, from the "El Morro National Monument" sign on the highway to directional signs and signs pointing out plant life to appeals and prohibitions ("El Morro Nat'l Monument is part of America's heritage. Please help protect it"; "It is unlawful to mark or deface El Morro rock"). If, as I suggested earlier, all cultures mark (and construct the meaning of) their territories, this bureaucratic, institutional inscription illustrates social conditions at the turn of the 21st century just as the petroglyphs and Spanish inscriptions illustrate earlier periods.

22. Murphy.

23. The panel states, "The Navajos surrendered in 1864 and more than 8,500 were forced to make the long walk of exile to Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico. After much suffering, they signed a final treaty in 1868 and were allowed to return to their homeland. Peace was established." It is possible to read the panel as being either sympathetic to the Indians or triumphalist (or both).

24. Slater, 49-50.

25. The use of the term "era" and the comparison of historical periods to geological eras further emphasize the difference between the "present" and "cultural" eras and the naturalness of the distinction. The exhibit is also vaguely evolutionary. In the corner of each of the five era signs are footprints: reptilian prints in the bottom two, a mammalian paw print in the middle, a bare human footprint in the "cultural" era, and a boot print in the "present" era. This iconography dangerously combines a narrative of species evolution and a historical narrative in such a way that it becomes possible to interpret the latter in terms of cultural evolution (the relationship between people who wear boots and people who walk barefoot is like the relationship between mammals and reptiles).

26. Sylvia Rodríguez, "Tourism, Whiteness, and the Vanishing Anglo," pp. 194-210 in Seeing and Being Seen: Tourism in the American West, ed. David M. Wrobel and Patrick T. Long (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001).

27. The theory of the colonial and tourist gaze (an institutionalized way of looking that reinforces power relations through objectification) further helps to explain this relationship between visibility and power. See Sylvia Rodríguez, "The Tourist Gaze, Gentrification, and the Commodification of Subjectivity in Taos," pp. 105-126 in Essays on the Changing Images of the Southwest, ed. Richard Francaviglia and David Narrett (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1994). Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1995 [1975]) has shown that rendering a subordinate group of people (such as prisoners) visible facilitates their discipline and control. I do not mean to imply that coercive and consensual forms of power are necessarily sequential or that the latter always supplants the former; both may be in operation at the same time.

28. Compare Carson, 16-18 and see also Murphy, 3, 15.

29. I found further evidence of the enduring desire to leave one's mark in a concrete drainage ditch along the trail between the visitor center and Inscription Rock. Several initials (including "K. A. Adams / Maint.") and the date 1996 were carved in the concrete. Also see Carson, 15, 19.

30. In addition to this display, a brochure entitled "Celebrating 100 Years of the Antiquities Act 1906-2006" was available to visitors when I visited in 2007 and provided basic information about America's first preservation law and the establishment of El Morro National Monument.

31. The guidebook visitors follow as they explore Inscription Rock notes that the dam was lined with concrete in 1942. (See El Morro Trails, 6.) Also, an internal document states that the construction of the dam and the subsequent rise in water level threatened a number of inscriptions (See National Park Service, El Morro National Monument, "First Annual Centennial Strategy for El Morro National Monument," Document (2007) available at http://www.nps.gov/elmo/parkmgmt/upload/ELMO_Centennial_Strategy.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2009.)

32. Ironically, the temporary centenary exhibit (an example of a new kind of interpretation at El Morro) took the place of the more old-fashioned "Let the Rock Tell the Story" exhibit, which was remounted after the centenary exhibit was dismantled.

33. Mogollón.

34. Later the chief of visitor services at the monument told me that Pueblo people were maintaining a living relationship to this ancestral site through their work with the park service.

35. See, for example, National Park Service, El Morro National Monument, "Inscription Preservation," Document (2009) available at http://www.nps.gov/elmo/naturescience/inscriptionpreservation.htm. Accessed March 6, 2009.

36. National Park Service, El Morro National Monument, "Indoor Activities," Document (2009) available at http://www.nps.gov/elmo/planyourvisit/indooractivities.htm. Accessed March 6, 2009.

37. Slater, 49-50.

38. See, for example, Mogollón.

39. National Park Service, El Morro National Monument, "Monitoring and Preservation." Brochure (2005) available at http://www.nps.gov/elmo/naturescience/upload/Monitoring%20and%20Preservation.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2009.

40. Outside the recent history of the West, other cultures have revered innovation and the new or cycles of change, preferring to demolish or recycle remnants of the past; and within Western societies certain segments of the population have always cared more about preservation than others. See, for example, Max Page and Randall Mason, eds, Giving Preservation a History: Histories of Historic Preservation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2004) and Patricia L. Parker, Keepers of the Treasures: Protecting Historic Properties and Cultural Traditions on Indian Lands (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1990).

41. This suggestion complements one of El Morro's goals for the National Park Service's Centennial Initiative: "We want the future to have many ingredients from the past—a broad community of stewards (employees, volunteers, neighbors, visitors, tribal peoples, scholars, artists, children and seniors) to study, to share, to question, to challenge, to fix, to honor, to innovate" (See NPS 2007). Education is a principal theme of this document.

42. Philip Burnham, Indian Country, God's Country: Native Americans and the National Parks (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2000); Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Robert H. Keller and Michael F. Turek, American Indians & National Parks (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1998); Mark David Spence, Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Although the park service and other federal land management agencies have begun to make some progress in recent years, they still have a long way to go in addressing these past injustices. In fact, the very notion of "federal land" raises vexing moral questions when we acknowledge that other people (now called "affiliated groups") had significant material and cultural ties to land and natural resources claimed by the federal government under varying circumstances. Some, but by no means all, of these groups were Native American. My discussion of justice at El Morro leaves aside for now these crucial concerns, focusing exclusively on interpretation.