Viewpoint

How to Treasure a Landscape: What is the Role of the National Park Service?

by Brenda Barrett

The word landscape has power. It evokes something bigger and grander than our immediate environment. It invokes the sweep of a great river valley, a vista of agricultural fields interspersed with farmsteads and small towns, a great park designed to pleasure the eye, traces of past industrial might, or even the other side of the mountain. We understand that certain landscapes have special value. The challenge is to translate such understanding into action: identify, protect, and sustain these valued landscapes for the future. Recent articles, books, and conferences have heralded a revival in this kind of visionary thinking,(1) identifying examples of large regional collaborative efforts that are underway across the nation. What better time than now to try this bold idea?

Working on a landscape scale has been advanced as a policy direction for the Obama administration. Great Outdoors America, the report of the Outdoor Resources Review Group, noted the importance of this work, recommending that "Federal and other public agencies should elevate the priority for landscape level conservation in their own initiatives and through partnerships across levels of government, with land trusts, other nonprofit groups, and private landowners to conserve America's treasured landscapes."(2) Advancing the National Park Idea,(3 )the report of the National Parks Second Century Commission, charged with defining the future of the National Park Service, has also strongly endorsed landscape-scale thinking. Some of the commission's top recommendations are centered on the agency embracing a 21st-century mission by "creating new national parks, collaborative models and corridors of conservation and stewardship, expanding the national park system to foster ecosystem and cultural connectivity" and by "enhancing park protection authorities and cooperative management of large land- and seascapes."

Whatever the term—"treasured landscape" or, more recently, "Great Outdoors America"—Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar has expressed his vision for a high level of attention to both National Park Service units and other large landscapes worthy of protection. The administration put the concept into action in 2009 with the issuance of Executive Order 13508 on the Chesapeake Bay.(4) The new order led with a declaration that the Chesapeake Bay is a national treasure for its ecological values and nationally significant assets in the form of public lands, parks, forests, facilities, wildlife refugees, monuments, and museums.

So the good news is that the table is set to think about really big places like the 64,000-square-mile landscape of the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed. (Figure 1) One of the challenges, out of many, in implementing this kind of effort is that many of the logical partners who care about the idea of landscape are already invested in specific historic preservation or natural resource conservation strategies. For this reason, if the public sector is going to step in and engage in this holistic landscape scale approach to our nation's special places, as the Department of Interior has been asked to do on the Chesapeake Bay, then there is a pressing need to synthesize programs and translate between the vocabulary and agendas of the different groups who want to preserve land, revitalize communities, restore historic landmarks, and save the environment. A barrier to getting started on this important work may be a lack of understanding about how existing programs deliver services and what has been ground-truthed and tested. With experience in so many of these areas, the National Park Service should take stock of all the possibilities.

|

Figure 1. Sailing on the Chesapeake Bay. (Courtesy of the Chesapeake Bay Program.) |

The Historic Preservation Framework

The National Park Service, together with the President's Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, serves as the nation's de facto cultural heritage ministry. The two agencies have developed finely tuned expertise in the classification and protection of the nation's official list of places worthy of preservation, the National Register of Historic Places.(5) The criteria for designation and the understanding of what is significant in our nation's past have expanded from landmark properties to historic districts to larger landscapes to places that have traditional cultural value.(6)

According to the National Register Information System, as of March 16, 2010, 85,540 properties are listed in the National Register, representing over 1.5 million individual properties. The richness of information is in part due to the program's administration in partnership with states, territories, and tribes, which brings many perspectives on what is significant in the history and cultural heritage of the nation. Although the program struggles with funding issues, particularly for the many new tribal historic preservation programs, it is a good model of partnership administration.

The National Register of Historic Places also has proved to be an adaptable framework with well-supported guidance through regulations and interpretive bulletins.(7) However, there are outer limits to the size of an area that may receive National Register recognition and with good reason. One factor is the mandates of the National Historic Preservation Act and regulations, which require federal agencies to take into account the impact of actions on properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. It should also be noted that an even higher standard of protection is provided by Section 4(f) of the U.S. Department of Transportation Act for federally funded transportation projects.(8) These regulatory requirements associated with recognizing the significance of a place or property have reinforced the careful delineation of what is identified as culturally significant(9) and cannot be easily merged with the overarching concept of a treasured landscape. However, the information offered by the national register programs is an essential starting point for dissecting and understanding the value of any landscape.

The Potential for Land and Water Conservation

Turning to the natural world, the role of the National Park Service does not have as well-developed a framework outside of national parks themselves. This is so, even though it was the environmental and land conservation world that pioneered ecosystem thinking and concerns about biodiversity and climate change which drive much of the impetus on landscape thinking today. The only program that recognizes and designates place-based resources is the National Natural Landmarks Program. While the goal of the program is to recognize the best examples of the nation's biological and geological natural features, the program has very limited funding and only 600 properties have been included in the list of landmarks.(10) Overall, the field of natural resource management has developed a vast body of research, extending from the individual species level to the characteristics of large watershed or the interrelationships of regional ecosystems. However, these well-developed concepts for recognizing places of high ecological value have not been reduced to a governmentally recognized programmatic approach.(11)

NatureServe, which coordinates the Natural Heritage Index(12) and has members in every state, provides some uniform information on ecological values with partners in all 50 states as well other countries in the Americas. However, it is managed by a nonprofit consortium and in some states struggles for funding and identity. The land conservation movement is similarly organized around nonprofit leadership. For example on the national level, the Land Trust Alliance offers technical assistance and accreditation standards in the field. Overall the conservation movement is strongly supported by nonprofits and some outstanding state programs funded by special taxes and set-asides. One indicator of the success of the movement is growth, over the last 25 years the number of land trusts has tripled to 1,700 organizations.(13)

The National Park Service at one time had a central role in administering funds in partnership with the states and territories from the Land and Water Conservation Fund(14) for the planning, acquisition, and development of natural resources for recreational purposes. As the funding for state assistance part of the Land and Water Conservation program waned and what funding remained in the program was was refocused on other federal priorities, the park service was reduced to a minor player in the conservation world beyond park boundaries.(15) Both the National Parks Second Century Commission Report and the Outdoor Resources Review Committee have recommended full funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund to benefit both federal and state programs. These recommendations may provide the National Park Service with an opportunity to build a more robust landscape-scale strategy around preserving critical habitat, open lands, and waterways for conservation and recreation both within and without park units. New ideas for conserving large land areas could be built through identifying the land conservation priorities that would connect the lands already protected by the efforts of the nation's many land trusts, the over three million acres of nonfederal land acquired in the past by the Land and Water Conservation Fund, and other public land holdings.(16)

The Opportunity to Coordinate State Programs

One low-cost contribution the National Park Service could make to a landscape-scale vision for resource management is a more integrated approach to the Historic Preservation and Land and Water Conservation Programs. By statute, both programs are administered as a state/federal partnership and a little cultivation of their common roots might help both programs flourish. Created in the 1960s to counterbalance the sprawling growth that was seen as diminishing the nation's cultural and natural heritage, both programs are now funded from a similar source, that is, primarily offshore gas and oil revenues. Both programs are also managed through a partnership with the National Park Service and have many parallel requirements for participation: the state governor designates a State Historic Preservation Officer(17) or a State Liaison Officer for the Land and Water Conservation program, funding is provided on a matching basis, and each state must prepare a plan with substantial public involvement directing the expenditure of the federal funds that are directed to it.

However, despite the resource management goals of both programs, there has been little impetus to coordinate the substantial efforts that the states and tribes have put towards qualifying and planning for the two programs. And the individual states have a variety of conventions and funding streams that make each of their programs a little different. But the mission of the two programs have more in common than most government efforts and in reaching towards landscape work together, they might find undiscovered benefits and chances to partner on projects. In addition, most states tap into significant community development and transportation dollars to achieve their conservation and preservation goals, which may provide more opportunities to leverage mutually beneficial projects.

A good place to begin coordination would be in the required State Historic Preservation and the State Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation(18) planning processes. Such coordination could lead to improved practices and more support to fully fund both programs. The National Park Service already has a leadership role in these programs, now would be an opportune time to focus planning around the unifying idea of working in a landscape. Finally, the agency could provide a forum to share the innovative, cutting-edge ideas that are being pioneered at the state level to identify cultural and historic landscapes, conserve large landscapes through dedicated funds, and programs that link the future of communities and public lands.(19)

The Time to Rediscover Existing Partnerships

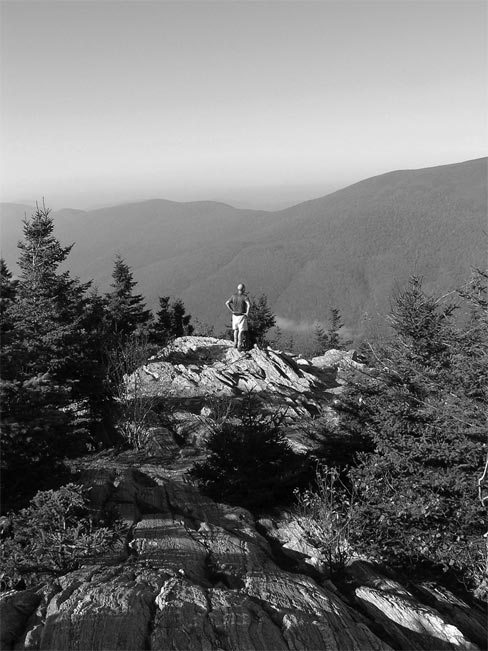

The National Park Service could lead by identifying the many programs in the agency's portfolio that are already operating on a landscape scale and learn how these small investments, backed by big ideas, can make a difference. One of the premier examples is the Appalachian Trail, which manages a 2100-mile cross boundary trail through a collaboration of volunteers and trail councils, with the National Park Service as a partner. (Figure 2) The trail partners are extending the value of the trail through educational and gateway community initiatives from Maine to Georgia. If just a little more attention were given to elevate and support the partnerships that manage the other 29 National Scenic and Historic Trails(20) that crisscross the nation, the impact on conservation and communities could be significant. This approach of involvement that engages the public beyond limits of the linear resources also could be applied to the designated waterways under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Program. Under the program's authority, the National Park Service manages 32 of the more than 150 designated wild and scenic rivers in the nation.

|

Figure 2. Vermont's Baker Peak on the Appalachian Trail. (Courtesy of Laurie Potteiger/Appalachian Trail Conservancy.) |

National Heritage Areas, the most rapidly expanding of the National Park Service's landscape scale designations, with 49 authorized areas from New England to Alaska,(21) provide another opportunity to see partnership in action. The National Park Service has been seen as an essential source of knowledge and support in planning and resource conservation expertise for the program. In turn, heritage areas have offered the agency access to empowered regional coalitions, local citizens, organizations, and government entities that collectively manage the heritage area and are responsible for its success. Most heritage areas have national park units within their boundaries and have developed mutually supportive partnerships on a regional scale. The approach has many benefits, but it is not without its challenges. The program is in need of a legislative foundation to tie together all the individual congressional designations. The growth of the program (from 18 areas to 49 areas in less than a decade) and the continued interest in designating new areas have challenged the National Park Service's ability to provide assistance. And finally, for the heritage areas to fully realize their potential, the National Park Service leadership must sustain and enhance this approach through long-term support and adequate staffing and budget.

In 2006, the National Park System Advisory Board report, Charting a Future for National Heritage Areas, recognized the potential for working on a grand scale and identified steps to maximize the benefits of the partnership, noting that it is an approach that embraces preservation, recreation, economic development, heritage tourism, and heritage education and weaves them into a new conservation strategy.(22)

Whether rivers or historic or scenic trails, roadways, canal systems, waterways, rail beds, or the more holistic scale of the heritage area or corridor, the National Park Service has discovered how to use regional resources as an effective organizing principle, bringing people together across political and disciplinary boundaries. These resources offer a unique opportunity to knit together a country that is challenged by fragmented local governments and different perceptions about conservation and preservation. Many of these efforts bring with them a host of partners who have pushed the agency to get involved in these special places where nature and culture combine and to look with the expressed wish of gaining the National Park Service imprimatur, as well as aid and assistance to the preservation of significant resources. These initiatives to work at larger and larger landscapes should now be embraced as the foundation of the treasured landscape idea. A historic opportunity would be missed if all this work were not folded into the way forward.

The National Park Service is only one of many players in any strategy to tackle the conservation of an ecosystem or preservation of a region's cultural heritage. However, because of its partnership with the states, tribes, and territories in the administration of both historic preservation and land and water conservation programs, the agency has a special responsibility to show leadership.(23) It has pioneered many regional initiatives around trails, waterways, and the nation's heritage. Importantly, the units of the national park system are themselves laboratories for integrated resource management because most incorporate cultural, natural, and historic values. The National Park Service has an unparalleled opportunity to use the full range of its existing partnerships, designation programs, and expertise to model collaborative landscape approaches and expand its stewardship mission both inside and outside park boundaries.

It's All about the Story

Finally, the National Park Service could lead through its demonstrated excellence in education and interpretation. This step is critical as coming to consensus on the value of a place is the first step toward taking action for its protection. The report of the Preserve America Summit, held in New Orleans in October of 2006,(24) revealed a much larger and more expansive definition of heritage values than are found under the current rubric of historic preservation. This expanded definition encompassed the natural and cultural as well as the historic values of the landscape, recognized living communities and diverse traditions, used heritage values, broadly writ, for the management of resources and was more centered on people and sense of place than on the features of the built environment.

One of many outgrowths of the broader view of heritage is the importance of narrative or "the story" in communicating to people where they live and how they are connected to the larger cultural landscape or ecosystem around them. In the National Heritage Areas Program, research in three different regions of the country has shown that telling the story of a region was the most essential step in engaging partners and communities across boundaries and generations.(25)

The National Parks Second Century Commission Report recognized the power of a public armed with knowledge of the country's history, natural resources, and "the responsibilities of citizenship."(26) To have any chance of building a sense of commitment to conserve a landscape as large as, for example, the Chesapeake Bay, there will need to be a narrative to match the scale of undertaking. Although daunting, it can be done. With very limited investment, the National Park Service manages the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program to coordinate preservation and education efforts nationwide and integrate local historical places, museums, and interpretive programs associated with the Underground Railroad into a mosaic of community, regional, and national stories.(27) If the time is right, a compelling regional narrative might provide the tipping point for action on a landscape scale.

In Conclusion

The definition of what is in the purview of the National Park Service has always been a dynamic process, as Congress has broadened the agency's mission from natural wonders, to historic landmarks, to outstanding recreational assets, and into the very living places in our nation and some of its hardest stories, whether the African Burial Ground in New York City or the Japanese internment camp Manzanar in California.(28) The expanding definition of the agency's work has brought the National Park Service into increasingly complex relationships with the landscape, and the agency and its partners need to seize this new opportunity to revitalize existing programs that recognize, organize, interpret, and preserve the resources that the service was created to protect. Now is the time to truly treasure our landscapes.

About the Author

Brenda Barrett is the Director of the Pennsylvania Bureau of Recreation and Conservation, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. She may be contacted at brebarrett@state.pa.us.

Notes

1. McKinney, Matthew J. and Shawn Johnson, Working Across Boundaries: People, Nature and Regions. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Center for Natural Resources and Environmental Policy, University of Montana, 2009. Steiner, Frederick R. and Robert D. Yaro, "A New National Landscape Agenda: The Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 is Just a Beginning," Landscape Architecture 99(6) (June): 70-77. Both works have built on years of work. Some of these efforts have also translated into calls for action and other resources. For web-based resources, see http://www.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/regional-collaboration/

2. Great Outdoors America, report of the Outdoor Resources Review Group may be found at http://www.orrgroup.org/

3. Advancing the National Park Idea: National Parks Second Century Commission Report (National Parks Conservation Association 2009) The report and the accompanying eight committee report may be found at http://www.npca.org/commission/. The quotes that follow are from page 17.

4. President Obama issued the Executive Order 13508 on Chesapeake Bay Protection and Restoration on May 12, 2009 at Mount Vernon overlooking one of the bay's might tributaries the Potomac River.

5. http://www.nps.gov/nr/ and http://www.achp.gov/. All cultural or historic units of the National Park System are also listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

6. NPS Bulletin 38 "Guidelines for Evaluating and Documenting Traditional Cultural Properties," Parker and King 1990. http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/nrb38/

7. http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/index.htm

8. http://www.environment.fhwa.dot.gov/4f/index.asp

9. While these provisions have undoubtedly preserved thousands of historic places, any expansive recognition of large landscapes and cultural regions is hampered by the understandable concerns of federal agencies and the many recipients of their largesse that they will be burdened by additional reviews and requirements. Additionally, the limits on funding levels for historic preservation grant assistance and the need to control the impact of federal tax credits for historic rehabilitation project also reinforce the need for selectivity. Direct federal aid to historic properties not under the ownership of the National Park Service is already very circumscribed. The Save America's Treasures Grants (not to be confused with the treasured landscape idea) are only available to properties that meet the criteria for National Historic Landmarks, the highest level of recognition.

10. According to the program's 2008 annual report, it employs one fulltime staff person and has a budget of only $500,000. http://www.nature.nps.gov/nnl/ 11. The Environmental Protection Agency's earlier proposal for environmental mapping and the program and the Department of Interior proposal for a national biological survey were not able to move forward. Steiner and Yaro, A New National Landscape Agenda, 72.

12. www.natureserve.org

13. www.landtrustalliance.org

14. Information on the history and current status of the National Park Service's role in the Land and Water Conservation Fund can be found at http://www.nps.gov/ncrc/programs/lwcf/. For information on the history of the program, see http://www.nps.gov/ncrc/programs/lwcf/history.html.

15. Within the National Park Service, the successful Natural Resource Challenge has directed significant appropriated dollars to natural resource research and restoration. One of the recommendations of the National Parks Conservation Association's National Parks Second Century Commission report speaks to the desirability of increasing the park service's role beyond park boundaries: "To strengthen stewardship of our nation's resources, and to broaden civic engagement with and citizen service to this mission. . . The Congress of the United States should: Encourage public and private cooperative stewardship of significant natural and cultural landscapes. Using the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act as a guide, enact legislation providing the National Park Service with authority to offer a suite of technical assistance tools, grants, and incentives—including enhanced incentives for conservation easements—to encourage natural resource conservation on private lands." (Advancing the National Park Idea [2009], 44).

16. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the organization that advises UNESCO on natural heritage listings, classifies the wide variety of protected areas that are found across the globe. These range from natural and wilderness areas that are strictly managed for environmental and ecosystem values (Category Ia and Ib)to protected landscapes and seascapes (Category V) that recognize the importance of the interaction of people and the land in creating a valuable resource. Category V landscapes have the virtue of recognizing the importance of places "where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced an area of distinct character" and incorporate in their recommended management objectives the need to support the social and cultural fabric of communities (http://www.iucn.org/).

17. Tribes are also important partners in the administration of the federal historic preservation program. Tribal Historic Preservation Officers are appointed by the tribe's chief governing authority. http://www.nps.gov/hps/tribal/thpo.htm

18. Recently the National Association of Outdoor Recreation Resource Planners has been looking at ways to improve the impact of State Comprehensive Resource Plans (SCORP) on state and federal policies. http://www.narrp.org/.

19. A number of states have significant programs to identify historical and cultural landscapes, one example is the Massachusetts Historic Landscape Preservation Initiative, (http://www.mass.gov/dcr/stewardship/histland/histland.htm) One of the most robust land conservation programs is Great Outdoors Colorado, which funds significant land conservation with lottery revenues http://www.goco.org/). Pennsylvania has developed a Conservation Landscape Initiative (CLI) as a place-based approach to coordinating the state's programs and strategic investments in seven distinctive regions of the commonwealth based on collective decision making and with a focus on linking public lands with their neighboring communities (http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/cli/index.aspx).

20. http://www.nps.gov/nts/info.html

21. http://www.nps.gov/heritageareas/

22. Charting a Future for the National Heritage Areas, National Park System Advisory Board (2006), http://www.nps.gov/heritageareas/NHAreport.pdf

23. I feel empowered to comment on these issues as a member of a small club who has served as both a Deputy SHPO (Director of the Bureau for Historic Preservation in Pennsylvania 1980-1984, 1986-2001) and Assistant State Liaison Officer (Director of Recreation and Conservation in Pennsylvania 2007 to present) with a transitional stint as NPS National Coordinator for Heritage Areas (Washington, DC 2001-2007).

24. Findings and Recommendations of the Preserve America Summit, President's Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Washington, DC (2007), http://www.achp.gov/.

25. Daniel Laven reports on the importance of telling the story of a region as the most important method to engage people in a large landscape, as described in Barrett, Brenda, "Valuing Heritage: Re-examing Our Foundations" in Forum Journal, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Vol. 22, No. 2, 30-34. (2008). Also see Tuxill, J., Mitchell, N., Huffman, P., Laven, D., Copping, S., and Gifford, G., Reflecting on the Past, Looking to the Future: Sustainability Study Report: A Technical Assistance Report to the John H. Chafee Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor Commission; Tuxill, J., Mitchell, N., Huffman, P., Laven, D. and Copping, S., Connecting Stories, Landscapes, and People: Exploring the Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor Partnership (2006); and Tuxill, J., Mitchell, N., Huffman, P., and Laven, D., Shared Legacies in the Cane River National Heritage Area: Linking people, Traditions and Landscape (2008). All by the Conservation Study Institute, Woodstock, Vermont.

26. Advancing the National Park Idea (2009), 16.

27. http://www.nps.gov/ugrr/

28. African Burial Ground (www.nps.gov/afbg/index.htm) and Manzanar (www.nps.gov/manz/index.htm)