Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Men of Wealth and Power Like Carolingian kings, attended by swarms of family, servants, and hangers-on, the rich and powerful moguls of New Spain's northern marches held court in their fortified adobe castles, dispensed justice like patriarchs, and welcomed travelers with prodigal hospitality. Because these hombres ricos y poderosos colonized, governed, and sustained vast reaches of the silver-rich north at their own expense, the king granted them notable, almost feudal independence. Not that he ever intended it to last. Always royal lawyers hovered about, eager to retract the privileges of an adelantado who defaulted. For their part, the frontier ricos kept agents at court, married their daughters to royal judges, and applied bribes and favors where they would do the most good.

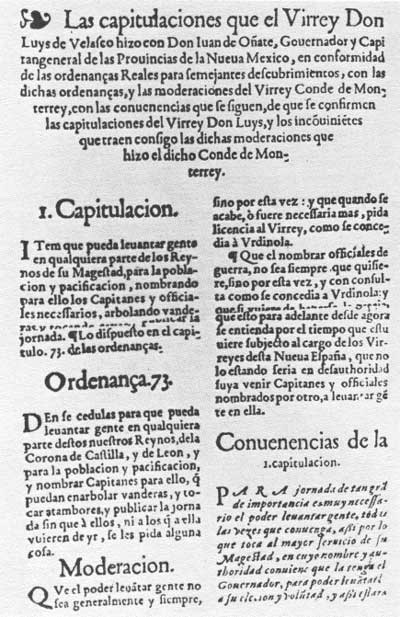

Juan Bautista de Lomas y Colmenares, master of Nieves north of Zacatecas, epitomized the feudal mentality of the northern barons. In 1589, one year before the Castaño de Sosa fiasco, don Juan Bautista had signed a contract for the pacification of New Mexico with Viceroy Marqués de Villamanrique, whose secretary happened to be Lomas' son-in-law. Not only did Lomas ask for the esteemed feudal title adelantado for his family in perpetuity, the office and authority of governor and captain general for six heirs in succession, and the noble rank of count or marques, but also, among other things, forty thousand vassals in perpetuity and a private reserve of twenty-four square leagues, or 120,000 acres! That was too much. Philip II did not want New Mexico that badly. Next, Viceroy Luis de Velasco entered into a contract with Francisco de Urdiñola, Lomas' archenemy. Its terms were more in keeping with the 1573 colonization laws, and for a time it appeared that the crown would accept Urdiñola's offer. Meanwhile Lomas fumed. By intrigue and influence, the lord of Nieves spun so tight a web of litigation, including the charge that Urdiñola had poisoned his wife, that his rival could not move. Velasco looked for another candidate. [1] For some time the viceroy had discussed the pacification of New Mexico with don Juan de Oñate y Salazar, a member of his intimate circle, a man whose "age, fortune, and talents" well qualified him to undertake the venture. Evidently this gentleman had excused himself previously from consideration because of his ailing wife. When she died, he found him self "free to negotiate." In September of 1595, Velasco signed a contract with him. The viceroy could hardly have done better.

Forty-seven years old, experienced in frontier affairs, and rich, Juan de Oñate had been born with a Zacatecas silver spoon in his mouth. His Basque, conquistador father Cristóbal de Oñate and father-in-law Juan de Tolosa were half of the Zacatecas big four. Through his recently deceased wife, Isabel Cortés Moctezuma, don Juan could claim both the conqueror of Mexico and the Aztec emperors as relatives. "From the time he was old enough to bear arms" he had fought Chichimecas and developed mines. Now, for stakes he deemed high enough, Juan de Oñate would gamble his fortune on the chance that he could make New Mexico pay. [2] Velasco had already accepted Oñate's offer to arrest and bring back from New Mexico another party of illegal entrants. One Capt. Francisco Leyva de Bonilla, commissioned by the governor of Nueva Vizcaya to punish some cattle-thieving Indians east of Santa Bárbara, had thrown off the governor's aurthority and made for New Mexico. There was no telling what harm "such unrestrained and audacious men would cause the inhabitants of those provinces." Therefore on October 21, 1595, when Velasco in the name of Philip II appointed Oñate "governor, captain general, caudillo, discoverer, and pacifier" of New Mexico, he charged him with a twofold mission: proceed against the traitor Leyva and pacify the land. [3]

Under the contract, Oñate committed himself to provision and take to New Mexico at least two hundred men and to supply thousands of head of stock, tools, and necessities, twenty carts, and a large personal outfit. All of this he hoped to have assembled at Santa Bárbara by March of 1596. Besides the governorship for two lifetimes, with all the many powers that went with it, don Juan was to receive the title adelantado as soon as he took possession. He was to govern independently of the viceroy, answering instead directly to the Council of the Indies in Spain. Velasco had been scrupulous in adhering to the 1573 ordinances. Where Oñate had bid too high, the viceroy cut him down—Oñate requested his offices for four lives but Velasco confirmed them for two. Oñate asked for a loan of twenty thousand pesos while Velasco authorized six thousand. Oñate bid for an annual salary of eight thousand ducats and Velasco countered with six. Even as recruiting lists were opened amid pageantry at the viceregal palace and to the beating of drums in Puebla, Zacatecas, and elsewhere, a new viceroy entered Mexico City. Luis de Velasco, Oñate's friend and patron, had been promoted to Peru. Instead of speeding don Juan on his way, as he might have done, the outgoing executive insisted that his successor study the contract and satisfy himself that all was in order. That cost Oñate two years. The Count of Monterrey listened to Oñate's detractors as well as to his friends. The New Mexico grantee was not really so rich. His father had badly mismanaged the estate. There were debts. Even if relatives and friends contributed, Juan de Oñate would be hard pressed. Carefully, the new viceroy studied the contract, along with copies of the Lomas and Urdiñola documents. He then proceeded to strike or significantly limit at least seven major concessions to Oñate. The one that most offended him was the New Mexico governor's independence of the viceroy and audiencias of New Spain. If aggrieved Spaniards and Indians in New Mexico could appeal only to Spain, reasoned Monterrey, Oñate's authority would be virtually unchecked. Besides, some concessions should be withheld until don Juan proved himself. The king could always reward him and his people later for a job well done. [4] Colonization Delayed Grudgingly, Oñate's agents accepted the changes. By late summer 1596, the governor had the bulk of the expedition on the road north from Zacatecas. Just as he was about to cross the difficult Río de las Nazas, a viceregal inspector, don Lope de Ulloa, overtook the lumbering train. He carried an urgent secret message. The king had suspended the expedition. Don Juan was to hold up the entire operation until further word from Spain. Stung by the unreasonableness of the order, Juan de Oñate did the only thing he could, he "took the royal cedula [decree] in his hands, kissed it, placed it on his head, and rendered obedience with due respect." Then he protested. Such a delay, if prolonged, could ruin him and others who had mortgaged all but their souls to join the venture. Hungry colonists would consume the provisions on the spot. They would disband overnight if they ever found out why the expedition had halted at the mines of Casco ten days short of Santa Bárbara. To prove that he had more than fulfilled his contract, as well as to reassure his impatient following, Oñate requested Ulloa to carry on with "the inspection, review, and inventory of the people, provisions, munitions, equipment, and other things he is taking." The livestock and stores already collected in the Santa Bárbara area could be tallied there and added to the inventory. When finally the count and appraisal of everything from laxative pills and horseshoe nails to jerked beef and colonist families was completed in February 1597, it was found that Oñate had indeed surpassed the requirements of the contract. Still he had to wait. [5] By casting doubt upon the financial capability of Oñate, the Count of Monterrey had opened the door to a rival pretender, don Pedro Ponce de León, wealthy Spaniard of Bail&te;eacun. Ponce proposed a contract to the Council of the Indies more favorable to the crown in every regard. For over a year Philip II played off the two contenders one against the other. Meanwhile Monterrey had taken up Oñate's cause, probably for no small consideration. Ponce's health and finances worsened. In the spring of 1597, the king, while keeping Ponce on the string, secretly instructed Monterrey to find out if Oñate was still in a position to proceed. If so, he was to be given the royal blessing. [6] A second inspection of the Oñate expedition, finally pulled back together again by December 1597 and encamped in the Santa Bárbara district, lasted more than a month. This time only 129 men passed muster, 71 short of the two hundred Oñate had agreed to take. When a cousin of means gave bond for another eighty soldiers and for shortages of equipment and provisions, the last obstacle fell away. The inspector took his leave at the Río Conchos. Some twenty-five miles farther on, the caravan halted for a month while an advance party scouted ahead and the Franciscans caught up. Then in March 1598—two years behind schedule—the colonizing expedition of Juan de Oñate moved out. [7]

Oñate's Friars It was no coincidence that Franciscans accompanied Oñate. Viceroy Velasco's ill-advised suggestion that members of all the religious orders, especially the Jesuits, should join in the spiritual conquest of New Mexico ran counter to more than half a century of tradition. [8] First on the scene in New Spain, the friars of St. Francis, beginning in 1524, had pre-empted whatever areas they chose—in the environs of Mexico City and Puebla, in the present states of Hidalgo, Morelos, and Michoacán, and in the vastness of Nueva Galicia and the Gran Chichimeca. The Dominicans who disembarked in 1526 found themselves already limited geographically by Franciscans. When the Augustinians arrived in 1533, they had to fit their apostolate into spaces left by the other two orders. Although the majority of Franciscans preferred to minister to the sedentary natives of central Mexico, other more venturesome grayfriars, explorers, military chaplains, and itinerant missionaries to the Chichimecas, laid their Order's claim to the north. Not until the last years of the sixteenth century did the energetic new Society of Jesus gain a foothold in the Sierra Madre Occidental and begin building a triumphal northwest missionary empire. Even then, the great arc stretching from Tampico on the Gulf of Mexico west to the foothills of the Sierra remained a Franciscan monopoly. As early as July 1524, seventeen sons of St. Francis had met in chapter in or near the Mexican capital and organized themselves as a proper "custody," or dependent administrative district, of the Spanish Franciscan province of San Gabriel de Estremadura. As the Custodia del Santo Evangelio, they elected one of their number custos, superior for a triennium, and designated four towns as sites for Franciscan houses, known as conventos, with Mexico City as headquarters. At each house, a designated friar acted as local superior, or guardian. Several members, called individually definitors, and collectively the definitory, made up a council to advise the Father Custos. So rapidly did the Franciscan ministry grow in Mexico that the order raised the custody of the Holy Gospel to full provincial status in 1535. The following year at their fourth triennial chapter, the members elected a Minister Provincial.

To the west and north in Michoacán-Jalisco, where the mother province of the Holy Gospel set out one of several custodies, the process repeated itself. In 1565, that custody came of age as an autonomous province, later splitting in two as the province of San Pedro y San Pablo de Michoacán and the province of Santiago de Jalisco. A 1573 shipment of twenty-three friars from Spain made possible the founding of the custody of San Francisco de Zacatecas in Chichimeca country. Despite the proliferation of custodies and provinces, Holy Gospel retained its primacy as the original Mexican province. Its principal house, which came to be called the convento grande, regularly served as the residence of the Franciscan commissary general of New Spain, overseer of the Order's entire Central and North American theater. [9] Oñate's contract called for six Franciscans, five of them priests and one a lay brother. As provided in the 1573 ordinances, they were to be outfitted for the expedition at the crown's expense. Early in 1596, the Holy Gospel province made the appointments, at the same time requesting through the commissary general of New Spain that the number be doubled.

Friars versus Bishops Just as the chosen six were about to set out "in keeping with Your Majesty's instructions that for the present only friars of this Order be sent," the bishop of Guadalajara hurled an unsuccessful challenge at them. Brandishing his episcopal dignity, he avowed that churches established in New Mexico "must belong to his diocese." At base this was more than another round in the unending jurisdictional feud between Guadalajara and Mexico. It was a typical confrontation between the secular, or diocesan, clergy of bishops and parish priests on the one hand and the regular clergy, or religious orders, on the other. Because of the immensity of converting and ministering to the New World, the popes had granted members of the religious orders authority to administer the sacraments, not only to their native converts but to the faithful as well. When the Council of Trent in principle returned the faithful to the exclusive care of the parish priest, Pius V restated the friars' right to administer the sacraments to all in the absence of a secular, even without the bishop's authorization. Extremely jealous of their privileges, the regular clergy on occasion tried to throw off the bishops' authority entirely. The bishop of Guadalajara's bid to assert his jurisdiction in New Mexico before the Franciscans entrenched themselves was only the beginning. For two and a half centuries, Mexican bishops would claim authority over the distant colony, and for at least half that long, the Franciscans would defy them. [10] Viceroy Monterrey had no intention of permiting shared jurisdiction in New Mexico. "This might give rise to dissension and clashes between friars and secular priests." While he awaited the confirmation of theologians and the audiencia, another dispute broke over the friars assigned to join Oñate. Without the viceroy's knowledge, one of them carried with him authority from the Inquisition to act as its agent on the expedition and in New Mexico. Almost immediately someone objected. The friar was a criollo, a Spaniard born in New Spain, as well as intimate friend of Oñate, "for which reasons he might in some way cover up whatever excesses don Juan and his people might commit." If, wielding the power of the Inquisition, he sided with Oñate against his superior and the other friars, he could retard missionary work among the Indians and scandalously split the church in the new colony. When the Holy Office refused to rescind the friar's commission, Monterrey prevailed upon the Franciscan commissary general to recall him. Not until the mid-1620s did the Inquisition formally extend its influence to New Mexico. [11] Oñate En Route At final count, Oñate's band of Franciscans numbered ten two short of the apostolic twelve requested. Led by Comisario fray Alonso Martínez, their superior in the field, they and their escort caught up with the expedition on March 3, 1598, while it was encamped near the Conchos. One venerable religious, later identified as don Juan's confessor, had been with the enterprise from the start, through all the delays and frustrations. He was the almost seventy-year-old Fray Francisco de San Miguel, "a saintly old barefooted and naked-poor friar." Eight of the ten were priests and two were lay brothers. Three Mexican Indian donados attended them. When the scouting party reported back, the whole train pointed north, stringing out in a narrow, dusty procession, miles long. Unlike previous entradas, which had detoured eastward down the Conchos, Oñate struck almost due north across the trackless Chihuahua desert. That way he gained the Río del Norte just south of present-day Ciudad Juárez. On its banks, the entire company from captains to oxherds assembled to see the resplendent adelantado take formal possession of New Mexico. It was Ascension Day, April 30. Personally nailing a cross to a living tree in the name of the Holy Trinity, the Blessed Mary, and St. Francis, Oñate prayed, "Open the door of heaven to these heathens, establish the church and altars where the body and blood of the son of God may be offered, open to us the way to security and peace for their preservation and ours, and give to our king, and to me in his royal name, peaceful possession of these kingdoms and provinces for His blessed glory. Amen." [12] | ||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||