Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

The First Spaniards It was early fall, the time when the maize plants begin turning brown, 1540. Twenty-two summers had passed since the conqueror Hernán Cortés first stepped ashore on the mainland of Mexico, to trade, he said. Now, eighteen hundred miles northwest of that dank tropical coast, a small column of helmeted Spanish soldiers marched across high, semi-arid country through arroyos, chamisa, and piñon to receive homage from the fortress-pueblo of Cicuye. Even though they numbered not many more than twenty, this medieval-looking detachment from the expedition of Gov. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado faithfully represented the conquering forces of Catholic Spain in America. The youthful captain, who wore a coat of mail and rode a horse covered with leather or quilted cotton armor, hailed his earthly Holy Caesarean Catholic Majesty in the same breath as his Heavenly Father. Having marveled firsthand at the incredible fruits of Cortés' success, he had willingly financed himself and his retainers for this venture of discovery. Several of the other horsemen had outfitted themselves and brought along black slaves. Behind them on foot marched four paid crossbowmen. Also on foot, in emulation of St. Francis, walked a gray-robed Spanish friar, a rigorous and visionary priest bent on conquest to the glory of God and the church militant. [1]

Capt. Hernando de Alvarado, from the northern mountain province of Santander, was probably light skinned with sandy hair and beard. In 1530, at age thirteen, he had crossed the Atlantic in the grand fleet that returned Cortés to México. He had served the conqueror, as he phrased it, "in the first discovery of the South Sea." Later, in the excitement of sensational reports from the far north, the well-born twenty-three-year-old Alvarado had signed on with Coronado as captain of artillery. During the battle for the Zuñi pueblo of Hawikuh, he and García López de Cárdenas shielded the fallen Coronado with their bodies and thereby saved the general's life. At least one chronicler later claimed that young don Hernando was kin to the more famous Pedro de Alvarado, hell-bent conquistador of Guatemala. [2]

At Alvarado's side rode Melchior Pérez. His father, Licenciado Diego Pérez de la Torre, had succeeded the notorious Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán as governor of Nueva Galicia. When the elder Pérez died in an Indian revolt, the viceroy appointed Coronado to the vacant governorship. The Pérez clan was from the villa of Feria in southern Extremadura just off the highroad between Zafra and Badajoz. Don Melchior had gambled a small fortune fitting out himself and his servants, more than two thousand gold castellanos he calculated. [3]

Juan Troyano, from the market town of Medina de Río Seco, northwest of Valladolid, had fought as a youth in the armies of Emperor Charles V in Italy. He had come to New Spain in the fleet that brought over Coronado and his patron, don Antonio de Mendoza, first viceroy of New Spain and heaviest financial backer of the expedition. Evidently Troyano possessed a flair for languages. He had already begun picking up phrases in various Indian tongues. He also, now or later, picked up an Indian girl, not unusual for a Spanish soldier. But Troyano refused to give her up, married her, and spent the rest of his life with her. [4] Unlike Troyano, Fray Juan de Padilla was profoundly disappointed in the Pueblo Indians, in all Indians for that matter. This belligerent Franciscan had joined Coronado for only one reason. He would, by the grace of God, find and reunite with Christendom the long-lost Seven Cities of Antillia. According to a popular romance of the time, seven Portuguese bishops fleeing the Moslem invasion of their homeland had embarked their congregations in the year 714 and sailed off to the west. They had founded seven immensely wealthy and utopian cities—cities that lay, Father Padilla was convinced, somewhere north from Mexico. Visits to both the Zuñi and Hopi pueblos had shattered his illusions that Cíbola or Tusayán might end his quest. Perhaps to the east, far to the east of Cicuye in the land of Quivira. A son of the Franciscan province of Andalucía in southern Spain, Father Padilla likely had been among the twenty friars shepherded to Mexico in 1529 by Fray Antonio de Ciudad Rodrigo, one of New Spain's revered original twelve. Padilla turned out to be a fighter as well as a visionary. He had joined earnestly in the war of Franciscan Bishop Juan de Zumárraga against the tyrannical first audiencia of Mexico, the ruling tribunal dominated by Nuño de Guzmán. He had taken part in the ill-starred venture of Cortés to build ships at Tehuantepec for exploration of the South Sea. He was quick tempered, obstinate, impatient, and, as the soldiers found out, a holy terror when aroused by swearing or alleged immorality. [5] Alvarado, Pérez, Troyano, and Padilla—these then, along with a handful of unnamed horsemen, crossbowmen, and servants, were soon to become the European discoverers of the populous stone pueblo of Cicuye. The Names Cicuye and Pecos Although most of the chroniclers of the Coronado expedition used variant spellings—Acuique, Cicúique, Cicuic—this word as spoken by the initial delegation from there, which sounded to Spanish ears like Cicuye, was probably the natives' own name for their pueblo. The people of Jémez, the only other Towa-speakers among the Pueblos, called Cicuye something like Paqulah or Pekush. That evidently became Peago, Peaku, or Peko among the Keres in between. From them, the Spaniards of don Gaspar Castaño de Sosa heard it forty years later. Hence the historic name Pecos. [6]

Cicuye was expecting them. Located as it was at the portal between pueblos and plains, the community had served for a century as a center of trade. Along with shells, buffalo robes, slaves, chipped stone knives, and parrots came news. The people of Cicuye must have learned of the Spanish presence along the gulf coast, of the Aztecs' fall, and of Nuño de Guzmán's rapacious forays up the west coast corridor soon after these events took place. They surely had heard reports of the itinerant white medicine man and his black spokesman—Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Estebanico—as they and two companions made their tedious way from coast to coast across the whole of northern Mexico. The black had come north again swaggering. He had made demands on the Zuñis, and they had killed him. Cicuye knew the details. [7] Next, Spaniards with their awesome horses and firearms had appeared before Hawikuh and defeated the Zuñis, less than two hundred miles away. The headmen of Cicuye must have met in council. Should they stand against the invader or ally themselves with him for purposes of trade or war? It was a basic question that would later turn clan against clan and rend the social fabric of the pueblo. Initially, Cicuye sent a mission of peace.

Coronado Meets Bigotes At Hawikuh, Coronado had received them as foreign emissaries. They told the general that they had learned of the arrival of "strange people," in Coronado's words, "bold men who punished those who resisted them and gave good treatment to those who submitted." The inhabitants of Cicuye wished to be allies. Their spokesman, a large, well-built young man, evidently a war captain, was dubbed by the invaders Bigotes because, according to chronicler Pedro de Castañeda, he wore long mustaches. Such a display of individuality was unusual for a Pueblo Indian. Probably Bigotes was a trader, well traveled, experienced, and somewhat affected by his dealings with foreigners. He may even have spoken some Nahuatl, the lingua franca of central Mexico, which would have been readily understood in the Spanish camp. [8] The embassy from Cicuye exchanged gifts with Coronado: buffalo robes, native shields, and headdresses, for artificial pearls, glass vessels of some sort, and little bells. The Spaniards were particularly intrigued by the large hides covered with tangled and woolly hair. The men of Cicuye described the buffalo as best they could. They pointed to a painting on the body of a Plains Indian lad in their party, from which the Spaniards deduced that the animals were big cattle. To receive formal homage from Cicuye and to see these cattle, Coronado appointed the ready Captain Álvarado.

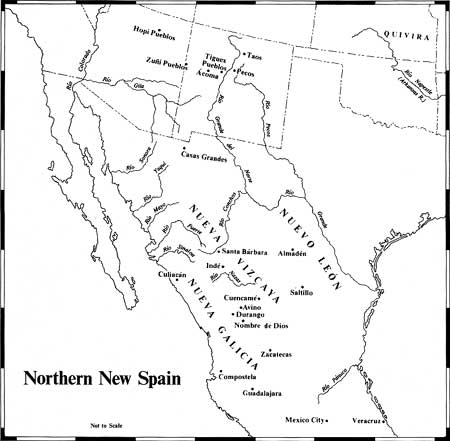

On the feast of the beheading of St. John the Baptist, August 29, 1540, Álvarado's squad had moved out from Zuñi, led by Bigotes and company. They had "discovered" invincible Acoma set on a rock twice as tall as the Giralda of Sevilla, then proceeded east to the cultivated valley of the Rio Grande, which they christened the Río de Nuestra Señora because they saw it first on September 7, eve of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin. They passed through the cluster of pueblos they called the province of Tiguex, and apparently traveled as far north as Taos, which Father Padilla thought might have had a population of fifteen thousand! Now in late September or early October, the first Europeans approached Cicuye. [9] | ||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||