Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

The 18th-Century Revolution in New Mexico If Fray Alonso de Posada had been resurrected in eighteenth-century New Mexico, he would hardly have recognized the place. Not that the Jornada del Muerto or the Sierra de Sandía looked any different; not that the mainly agricultural subsistence-level economy had changed, or the pattern of trade and hostilities with surrounding nomads, or the drought, disease, and isolation, but rather, the colony's very reason for being. The Pueblo revolts and the reconquest by Diego de Vargas—set in the larger context of an increasingly secular world—had thrust up a watershed. The blood of the martyrs flowed back to the age of spiritual conquest, the age of Fray Juan de Padilla and Fray Alonso de Benavides, while the tide of the future ran on toward the mundane, toward colonial rivalry, solicitation of sex in the confessional, and even constitutions. Defense had replaced evangelism. Friars no longer dictated the affairs of the colony. The primary concerns of the Spanish Bourbon kings and their colonial bureaucracy were defense and revenue, not missions. Where missionaries held or strengthened imperial frontiers, as they did in New Mexico, they continued to receive compensation from the crown. Still, the mission payroll declined in proportion to that of the military. In 1763, thirty-four Franciscan priests received an annual sínodo, or royal allowance, of 330 pesos each, and one lay brother, 230, for a total of 11,450 Pesos—as compared to 32,065 pesos for the Santa Fe garrison. The salaried presidial, too often ill-equipped, poorly trained, and abused by his officers, had replaced the soldier encomendero. In New Mexico, the encomienda system, dying all the empire, did not survive 1680. [1] No longer did Franciscans control the economic lifeline of the colony. The government-subsidized mission supply service that operated for much of the seventeenth century was not restaged in the eighteenth. Instead, like everyone else, the friars made their own arrangements for freighting. The missions' combined wealth, using the word loosely, fell in proportion to that of the steadily expanding Hispanic community. Few pre-revolt families returned. The settlers who came with Vargas and those who came later wrought, in effect, "a new and distinct colonization." By 1799, a census, including the El Paso district, showed 23,648 of them—and only 10,557 Indians. [2] Although friars continued as the only priests to the vast majority of New Mexicans, they saw their monopoly of the local church seriously undermined in the eighteenth century. Three bishops of Durango actually appeared in the colony on visitations—Benito Crespo in 1730, Martín de Elizacoechea in 1737, and Pedro Tamarón in 1760. Crespo appointed New Mexico-born don Santiago Roybal, whom he had previously ordained at Durango, as his vicar and ecclesiastical judge in Santa Fe, an opening wedge for the secular clergy. A Franciscan still served as agent of the Inquisition, but his authority was only a shadow of what it had been. Compromised by the "flexible orthodoxy" of reforming Bourbons, the Holy Office now too often spent its energy hairsplitting or protecting its own privileged status. As guardian of traditional Hispanic values against the blasphemy of the Enlightenment, it had little business on an illiterate frontier. Unless the governor of New Mexico happened to profess French philosophy, Protestantism, or Freemasonry, unless he had two wives or was grossly immoral, he ran little risk of accusation, arrest, or trial by the Inquisition, even when he trod on the friars' toes. At times, in fact, the tables were turned. Denunciation of the missionaries themselves for solicitation or worse became a weapon of the laity. [3] Most of the bluerobes ministered faithfully to their motley flocks of Indians and Hispanos, even under the most trying conditions. Some were sorely perplexed by the conflict inherent in being both missionary and parish priest, striving to observe with the right hand the Rule of St. Francis, while accepting with the left, fees for services rendered. Some broke under the strain. A few were scoundrels. Overall, it would seem, the quality of the clergy did decline in eighteenth-century New Mexico. Within the Order, missionary momentum shifted from the provinces to the newly formed missionary colleges whose grayrobed friars answered the call to Coahuila-Texas, the Californias, and Sonora-Arizona. Nothing wounded the dedicated, beleaguered New Mexico missioner more than the gaping disparity between the pious expectations of the seventeenth century and the scabby reality of the eighteenth.

The Administration of Cuervo y Valdés Diego de Vargas, heroic reconqueror and strutting peacock, was dead. The viceroy, then the Duke of Alburquerque, hastily appointed a governor ad interim, one don Francisco Cuervo y Valdés, knight of the Order of Santiago, who entered Santa Fe in March 1705. By the end of that year, Cuervo had recruited enough settlers to found a new villa in the Bosque Grande de doña Luisa, the future Albuquerque. He had arranged for the repeopling of Galisteo with some of the dispersed Tanos. He had waged war on Navajos and Apaches, and he had presented to don Felipe Chistoe of Pecos and to other loyal Pueblo leaders "suits of fine woolen Mexican cloth like that used by the Spaniards" along with "white cloth for shirts, as well as hats, stockings, and shoes." The rest of the time, don Francisco spent trying to convert his interim appointment to a regular one. The Pueblo Indians considered Cuervo a savior, or so he tried to convince the crown. At a concourse of their leaders who came together in Santa Fe in January 1706, these natives, on their own volition says the document, begged through their protector general, Alfonso Rael de Aguilar, that "don Francisco Cuervo y Valdés be continued and maintained in this administration for such time as is His Majesty's will, so that they might enjoy not only the blessings of peace but might also make progress in those things which they hoped to achieve through his Catholic and successful programs, of which they were very certain because of what they had already experienced of his prompt and sure actions." Representing the Pecos, as usual, was the Spanish-speaking don Felipe Chistoe. [4] Along with the Pueblo leaders' plea that he be retained in office, Cuervo sent to the viceroy a supplication by Custos Juan Álvarez. The missions of New Mexico desperately needed vestments, chalices, and bells. They needed reinforcements, another thirteen friars in addition to the twenty-one already granted. Payment of their travel expenses had fallen three years behind. They lacked even wine and candles for Mass. In some missions, according to the prelate, "the chasuble is of one color, the stole of another, and the maniple of still another; and, they are without bells with which to call the people to catechism." To document his statement Father Álvarez supplied a mission-by-mission account of the custody.

A Basque from the salty coastal villa of Lequeitio, half way between Bilbao and San Sebastián, Fray José de Arrangui had professed at the Mexican Convento Grande on April 20, 1695, and had already begun his ministry in New Mexico by the year 1700. Pecos, where he baptized, married, and buried between August of 1700 and August of 1708, seems to have been his first and perhaps his only missionary assignment. How often he actually resided at the pueblo is hard to tell, but probably not often. For much of the time he served as notary and minister of Santa Fe as well. As secretary, he cosigned Custos Álvarez' glum report of January 1706. [6] New Church at Pecos Despite their inclination to look on Pecos as a visita of Santa Fe, the Franciscans did superintend the construction of a proper new church at the waning pueblo. Curiously, less is known about the building of this one than about either Zeinos' temporary reconquest chapel or the great pre-Revolt monument of Andrés Juárez. Custos Álvarez said about Pecos, "They are beginning to build the church." But he said the same thing about fifteen other pueblos, including Ácoma where the massive seventeenth-century structure had survived 1680 almost intact. Perhaps by sometime in 1705, Arranegui had made a start. An equally elusive statement, by the hyperobservant Father Visitor fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez in 1776, suggests 1716-1717 as the completion date. After counting the roof beams, "well wrought and corbeled" by Pecos carpenters, thirty-eight over the nave, twenty over the transept, and ten over the sanctuary, Domínguez noted a brief Latin inscription "on the one facing the nave: Frater Carolus. The inference is," he continued, "that a friar of this name was the one who built the church, but it is impossible to identify him since the individual is not identified by his surname." [7]

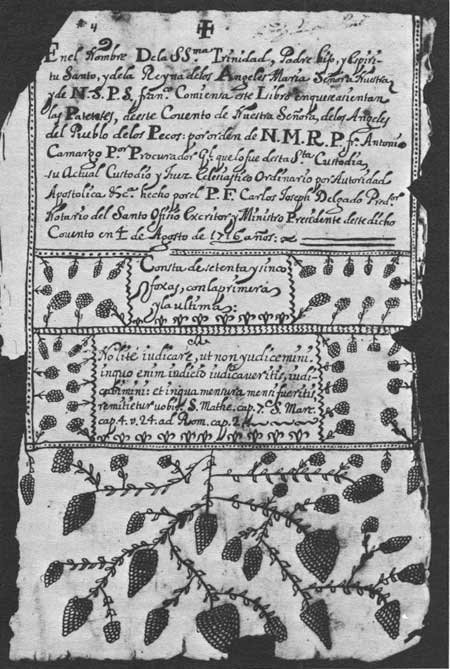

The Apostolic Fray Carlos The only friar named Carolus, or Carlos, who ministered at Pecos, or for that matter anywhere in the custody up to 1776, was an eighteenth-century Andrés Juárez named Carlos José Delgado. Described later as an "apostolic Spaniard," Delgado had been recruited from the province of Andalucía for the missionary college of Querétaro, had transferred to the province of the Holy Gospel, and in 1710 had arrived in New Mexico where he was to labor for forty years. By August 4, 1716, Fray Carlos, "ministro presidente" at Pecos, was bent over a desk in the convento decorating the title page of a new book for patentes, the official letters of exhortation and instruction from Franciscan superiors, which were regularly copied into such books at all the Order's houses. Although Delgado's baptismal and burial entries, which might have mentioned a "new church," are missing, his marriage entries survive, and they are distinctive. He wrote in a heavy, legible hand, and he filled the margins with garlands of curious, snowball-like flowers. Chronologically, the entries are bunched, seven in December-January 1716-1717, seventeen in April-May 1717, and three in October 1717, suggesting that he too divided his time between Santa Fe and Pecos. [8]

"The construction was done," wrote Fray Juan Miguel Menchero in 1744, "through the industry and care of the Fathers of the mission without having spent even a half-real of His Majesty's funds." The church, in his estimation, rated the adjectives "beautiful and capacious." Like Zeinos' chapel, it faced west, and it sat entirely on top of the mound covering Andrés Juárez' much larger fallen temple. The new church had barely three thousand square feet of floor space, compared to well over five thousand in the Juárez structure. But now there were fewer Pecos, not half as many. [9]

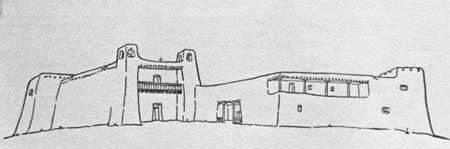

This was the fourth and final Pecos church. As late as 1846, eight years after the last few Pecos had abandoned the pueblo, artist John Mix Stanley of Lt. W. H. Emory's command sketched the deteriorating structure much as Father Domínguez had described it in 1776. Emory's comment that the details of the church "differ but little from those of the present day" is as true now as then. Its facade, flanked by twin bell towers rising barely above the flat roof, could hardly have been more typical of New Mexico church architecture. Between the bell towers, which jutted forward several feet forming a shallow narthex, and above the eight-foot-tall, two-leaved door, ran a wooden balcony with balustrade and roof. To get out onto it, said Domínguez, one exited from the choir loft through a window. Unlike the monumental seventeenth-century Juárez church, this one had neither buttresses nor crenelations, but it did have a transept. The floor plan was cruciform. In profile, the roof line ran straight back from the bell towers and stepped up at the transept allowing for a wooden-grated "transverse clearstory light." The outside, or north side, of the building presented one great expanse of adobe wall broken only by a single high window at the north end of the transept. On the south side, which looked out over the convento, there were at least three high windows. To reach the main door in 1776, it was necessary to enter the cemetery through a gate in the high wall directly in front. The porter's lodge and two-story convento were on the right. Once across the cemetery and inside, Father Domínguez found the dim interior of the church "rather pleasant." Above his head as he entered was the choir loft, to his right a door leading through Zeinos' dilapidated chapel to baptistery, sacristy, and convento beyond. The church floor was packed earth. Under it lay most of the baptized persons who had died over the previous sixty or seventy years.

Five steps led up to the sanctuary. Over the main altar, a movable wooden one, hung an old framed oil painting of Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles and another, somewhat newer, of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, as well as eight lesser oils arranged around the other two. In both arms of the transept stood wooden altars surmounted by paintings, some on buffalo hide. Evidently the Pecos church boasted no statuary at all. Virtually nothing escaped Domínguez' eye. In the nave, there was a well-constructed wooden pulpit in its usual place on the epistle side, and on the gospel side "a pretty wooden confessional on a platform," then a long bench with legs. He described the sacristy and inventoried everything he found, item by item, from chasubles to thurible to missal. Next he toured the convento downstairs and up, identifying cells, store-rooms, and stables. Upstairs, only the rooms on the south side were usable in 1776. The others needed repair. Good miradors looked out to the south and the west, and in the southwest corner stood a fortified tower. "When there are enemies," he noted, "a stone mortar is installed in it." [10] In all, the physical plant at Pecos was more than adequate. The church, constructed sometime between 1705 and 1717, may even have deserved the adjectives "beautiful and capacious." If the friars' ministry to the Pecos in the eighteenth century proved ineffectual, as some of them admitted it did, the reasons lay beyond a proper church and a place to live. Those they had.

Hit-or-Miss Ministry at Pecos For one thing, their ministry lacked continuity. Few of the friars stayed at Pecos long enough to implement a regimen, to learn the language, or to win the people's confidence. Between 1704 and 1794, the Pecos saw a constant parade of missionaries, at least fifty-eight! In the previous century, the able Andrés Juárez had lived with them for thirteen years, from 1621 to 1634. Now during the same length of time, 1721 to 1734, eleven different missionaries signed the Pecos books. Not that they were intensifying their ministry, much as they might have wished to, quite the contrary. Mostly they were ministros interinos, temporary pastors visiting from Santa Fe to provide a minimum of essential services and the sacraments, for the custody was almost always undermanned. Besides that, the superiors found themselves hard put to keep their missionaries in the field. Time and again they had to reiterate the prohibition against coming to Santa Fe without permission. Relatively speaking, Santa Fe was civilized and secure. Between Apaches and Comanches, the pueblo of Pecos was perilous and isolated. Its people, too, were dying off. The population dropped steadily, from perhaps seven or eight hundred early in the century to a mere ninety-eight adults and forty-four children in 1792. [11] Despite their beautiful and spacious church, their Christian veneer, and their commitment to military and trade alliances with Spaniards, the Pecos, like most Pueblos, held tenaciously to their traditional society and religion. To them, the friars' neglect was salutary. To them, Father Domínguez' matter-of-fact acceptance of their nine kivas in 1776 was a triumph of sorts. Diego de Vargas had spared the kivas, but a couple of his successors, harking back to the anti-idolatry campaigns of the previous century, had not. | ||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||