Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

The Inquisition as a Weapon of the Friars Back in the early 1620s, the unshrinking Fray Esteban de Perea, locked in close combat with Gov. Juan de Eulate, had appealed for help to the tribunal of the Inquisition in Mexico City. The Holy Office had responded positively, appointing outbound Custos Alonso de Benavides as its first comisario, or agent, for New Mexico. The Inquisition's presence, comforting to the devout and dreadful to the accused, was broadcast, and reaffirmed periodically, by the formal reading of an Edict of the Faith. For the unburdening of their consciences, anyone with information regarding thought, word, or deed against the Holy Mother Church must come forward and confess it. The local agent had authority to investigate alleged threats to the purity of the Faith by members of the Hispanic community, to summon witnesses and record their testimony, and to recommend and, upon receipt of approval, to execute the arrest and deportation of the accused to Mexico City for trial before the tribunal. Whether the Inquisition's presence in this rude, superstitious, ingrown frontier society made New Mexico a better place to live or not, it did put a formidable weapon in the hands of the friars. Eulate had left the colony just in time. The governors who succeeded him had cooperated with the friars more or less. Agent Benavides devoted most of his considerable energy to expanding the mission field. Then, during the thirties when church-state relations had deteriorated once again, when the friars really needed the muscle of the Inquisition, local agent Perea grew old and died. The rough and merciless Governor Rosas had taken every advantage. In the sixties, it would be different. Another governor who shared Rosas' greedy expectations and his disdain for the missionaries would find himself shackled in a wagon bound for the prison of the Inquisition in Mexico City.

Because they were considered perpetual minors in the Faith, Indians who retained their Indian identity were exempt from prosecution by the Inquisition, which was not necessarily a blessing. Mission discipline, depending on the friar in charge, could be much more arbitrary and even sadistic. Serious cases involving Indians—apostasy, heresy, and the like—went not to the Holy Office, but to the bishop, or in New Mexico, to the Franciscan prelate. In a society that considered the church an arm of the state and vice versa, crimes against the Faith and treason commingled. In cases of alleged Pueblo sedition, it was the royal governor, generally with consent of the friars, who sentenced them to the gibbet or slave block. The Pecos may not have understood the workings of the Inquisition, but it touched their lives. Several times during the 1660s, the agent resided at Pecos. Witnesses came and went. Two important Spaniards whom they knew all too well, their encomendero and a plains trader, were arrested and carted away. Then one night, the royal governor rode out to Pecos, entered the convento with armed men, and removed the agent to Santa Fe. Such acts cannot have enhanced the Pueblos' respect for their contentious, overbearing masters. The meticulous, sometimes shocking, and often wearisome records of the Inquisition provide a keyhole view of society in seventeenth-century New Mexico. Seen from there, 1680 comes as no surprise.

Governor López versus Ramírez Don Bernardo López de Mendizábal, governor of New Mexico from 1659 to 1661, was a petulant, strutting, ungracious criollo with a sharp tongue and enough education to make himself dangerous. Even before the caravan left Mexico City, don Bernardo and Fray Juan Ramírez, another contentious criollo, had quarreled over their respective jurisdictions. Ramírez, appointed procurator-general of the New Mexico custody to succeed the illustrious Fray Tomás Manso, had also been elected custos. As the wagons rumbled north, Franciscan prelate and royal governor carried on their own petty war. Ten of the twenty-four friars bound for the missions deserted in protest. López blamed Ramírez and Ramírez blamed López. Both would have their day in court. Both, within three years, would stand accused before the Inquisition. [1] Arriving in mid-summer 1659, Governor López de Mendizábal took over from Juan Manso while Custos Ramírez relieved Fray Juan González. Ex-governor Manso, younger brother of Fray Tomás, had got on tolerably well with the Franciscans and had aided them in their efforts to found missions in the El Paso area. As was customary, he remained in the colony for López to conduct his residencia. Ex-custos Juan González, who had been in New Mexico since at least 1644, stayed on as a definitor of the custody and as guardian at Pecos. Coincidentally, Father González and the Manso clan—Fray Tomás, veteran head of the mission supply service, provincial, and bishop of Nicaragua; his brother Juan, governor from 1656 to 1659; and their nephew Pedro Manso de Valdés, later lieutenant governor—all were born in the tiny, picturesque Asturian seaport of Luarca on Spain's windblown north coast. In America, nineteen-year-old Juan Gonzaléz had pronounced his religious vows on the feast of St. John Chrysostom, January 27, 1624, at the convento in Puebla. With studies and ordination behind him, he must have ridden north with his paisano Tomás Manso in one of the caravans of the 1630s. He was at Santo Domingo in September 1644 to sign the missionaries' fervent defense of their conduct. Although he may have served during the 1640s or 1650s at Pecos before his term as custos, Gonzaléz did nothing indiscreet or outstanding enough to inscribe himself in the scant records that survive. [2] The friars' alleged snubs of López de Mendizábal and the governor's refusal to receive Custos Ramírez in Santa Fe as ecclesiastical judge ordinary set the tone of church-state relations for the next two years. What the governor did in the name of Indian reform, and in his own economic best interest, the Franciscans saw as open interference in mission affairs. On his visitation of the colony, which by law every governor was supposed to make, López sought to win over the Indians at the misionaries' expense. The governor inspected Pecos, probably during the "trade fair" in 1659, but details are lacking. At nearby Galisteo in the presence of ten Spaniards, among them Pecos encomendero Francisco Gómez Robledo, don Bernardo grilled the Indians, men and women, one by one, under pain of death, about the personal life and habits of the missionary. "I am certain," protested Fray Nicolás del Villar, "that no prelate of mine would have made such a rigorous examination of any religious, and with so many and such exquisite questions, as His Lordship made of each of the natives." [3] López Opposes Unpaid Labor More serious than his effort to defame the friars themselves was López' attack on their use of free Indian labor. Early in his administration, the governor by decree raised the standard Indian wage from half a real per day to one real plus food. He then tried to impose it on the missionaries, who had long enjoyed the services of mission Indians without paying wages as such, In their defense, the Franciscans cited a 1648 decree by Gov. Luis de Guzmán y Figueroa, based on a royal cedula, exempting from payment of tribute the pueblo governor as well as natives employed "in service to the churches and divine worship," namely "an interpreter, a sacristan, a first cantor, a bellringer, an organist where there was an organ, a shepherd, a cook, a porter, a groom." The reference to organists seems to confirm that the órganos reported earlier in the 1640s at Pecos and other missions were indeed instruments and not merely choirs skilled in polyphonic chant. Up to the time of López, the friars had claimed these ten exemptions for mission staff. [4] According to much-abused Father Villar at Galisteo, the cavalier López relieved the women who baked the friar's bread and told them never to bake for him again. The royal governor then ordered the other servants of the convento to pay tribute—tanned skins and mantas—"for no other reason than having served." When López found out that Villar, who had been at Galisteo only a year struggling with the Tano language, still relied on an interpreter "he sent the latter off to a ranch to break young bulls." Next López had forbidden any Indian to carry a message for the friar and had removed the native fiscales of the pueblo, ostensibly because only the king—not the missionaries—could name them. As a result, the friar's hands were tied, he had no one to bake his bread, no way to preach to the Indians or impose discipline. In short, his ministry was doomed. [5] To counter the charges he knew the Franciscans were lodging with the viceroy, Governor López de Mendizábal set down charges of his own against them. They ran the usual gamut, from oppression of mission Indians and wanton misuse of their quasi-episcopal powers to blatant clerical immorality. When Franciscan Vice-custos García de San Francisco excommunicated Nicolás de Aguilar, López' heavy-handed agent in the Salinas district, the governor challenged his authority to act as anything but a parish priest to the laity. At López' bidding, witnesses gathered round. Concerning the arbitrary and contemptuous use of excommunication and absolution, Juan González Lobón, whom the friars considered a buffoon, testified that Fray Juan González of Pecos had absolved him "with some quince bars." The witness claimed that he was not informed why he had been excommunicated. Nevertheless, the friar fined him thirty cotton mantas for which González Lobón gave a draft on his encomienda receipts "to rid himself of his vexation." [6] The Alcaldes Mayores To squeeze the colony for every manta and every last fanega of piñon nuts he could, López de Mendizábal relied on his appointed district officers. In New Mexico, the alcalde mayor, sometimes called a justicia mayor, who presided over local affairs in one of the colony's six or eight districts, or jurisdicciones, served unsalaried and at the governor's pleasure. He administered petty justice, settled minor disputes over land and water, supervised the use of Indian labor, rallied the local militia, and helped the friars maintain discipline in the missions—any or all of which could be turned to his own profit and that of the governor. An alcalde mayor could be the missionary's best friend or his worst enemy. In the Salinas missions, the friars branded Nicolás de Aguilar the Attila of New Mexico. [7] López de Mendizábal's man in the Galisteo (Tanos) district, which also included Pecos, was Diego González Bernal. He, like Aguilar, carried out his governor's orders with gusto, as in the case of alleged fornication against the old friar at Tajique. It is not known how early an alcalde mayor was appointed for the Galisteo-Pecos jurisdiction. Back in the mid 1640s, the friars had accused Governor Pacheco of appointing such officials in most of the mission areas where only Indians lived, "a thing never done before." Although González Bernal surely had predecessors as "alcalde mayor and military chief of Galisteo and its district," their names are lost. In the documentation for López de Mendizábal's residencia, there is a packet of two dozen letters from him to González Bernal. The governor wrote of his stormy relations with the friars, of competition with them for Pueblo Indian labor, but mainly of day-to-day business affairs. Multiplying this correspondence by the number of the governor's other agents and appointees gives a fair idea of his economic vise grip on New Mexico. [8]

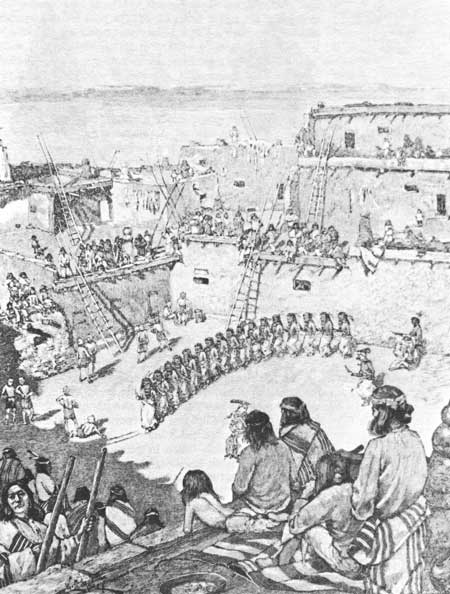

The Governor and Kachina Dances Another of the duties of an alcalde mayor was to announce in all the settlements and pueblos of his district, through an interpreter where necessary, the decrees of the governor in Santa Fe. When, to the horror of the friars, López de Mendizábal decreed that the Indians should resume their ceremonial dances, González Bernal did his duty. According to the missionary at Galisteo, the Tanos of that pueblo, San Cristóbal, San Lázaro, and La Cíenaga were only too happy to oblige with "some evil and idolatrous dances called kachinas, from which idolatry followed in these pueblos." Even worse, a rowdy group of Spaniards "had got themselves up in the manner of the Indian kachinas and had danced the dance of that name at the pueblo of San Lázaro and afterwards did the same at their house next to Galisteo." One of them danced in a shocking state of undress. At Pecos, Fray Juan González reported no such brutish goings on. [9]

López under Fire For Bernardo López de Mendizábal, 1660 was the year his fortunes turned. While he and his men kept on extorting a goodly profit in New Mexico, the charges against them were piling up in Mexico City. The first reports critical of the López administration reached the viceroy early that year. He sent copies over to the Holy Office. In the spring, the friars' special messenger and Custos Ramírez, whose supervision of the supply service required him to return to the viceregal capital with the wagons, both testified before the inquisitors against López' regime. Other messengers arrived with atrocity stories: missionaries dishonored and persecuted; Indians, undisciplined, reveling in the old pagan rites "with costumes, masks, and the most infernal chants," goaded by Spanish Christians. If relief did not come soon, one friar told the Holy Office in September 1660, the Franciscans would withdraw from New Mexico. And it was not only the Franciscans. In an effort to make capital out of former governor Juan Manso's residencia, López de Mendizábal had stalled and then locked up his predecessor. But Manso, with the aid of disenchanted New Mexicans, had escaped. Within four months, he stood before the tribunal of the Inquisition. López, meanwhile, sent Sargento mayor Francisco Gómez Robledo off to Mexico City with a defense of his actions and a packet of countercharges against the dictatorial, scandal-ridden Franciscans. Unfortunately for don Bernardo, messenger Gómez never made it. By the end of 1660, the Franciscan superiors had chosen as custos of New Mexico a tough young veteran who had served there during the mid-fifties but who had left before López and his gang took over. He was Alonso de Llanos y Posada González, who signed himself Fray Alonso de Posada. The Holy Office made him its comisario and charged him to carry out the most thorough investigation. The viceroy, who normally would not have appointed another governor for a year, yielded to the outcry from New Mexico and did so in 1660. He chose don Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa Briceño y Berdugo, an accomplished rogue. Together, Posada and Peñalosa would make don Bernardo pay more dearly than he could ever have imagined. [10] | ||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||