Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

Trade Fairs at Pecos The annual fall trade gatherings at Pecos, sometimes called rescates and sometimes ferias, held up as long as the Plains Apaches did. Governor Peñuela, accused of usurping "the trade that comes to the pueblos and frontiers of Taos, San Juan, and Pecos," answered his critics in 1711. The Pecos, at Peñuela's bidding, testified

Peñuela, at pains to show how his employment of Pecos Indians on church construction in Santa Fe benefited them in their trading, explained why he had paid each worker two awls instead of the usual trade knife. Earlier in the year, he had sent to Parral for thirty dozen "Madrid knives." These, along with many other goods on the governor's account, had been lost en route in an attack by hostile Suma Indians. Unable to acquire any iron elsewhere, Peñuela ordered some iron bars intended for use in the mines broken up as well as plow shares for the presidio's fields. From this, master blacksmith Sebastián de Vargas made a great quantity of awls, two of which the governor gave to each Indian.

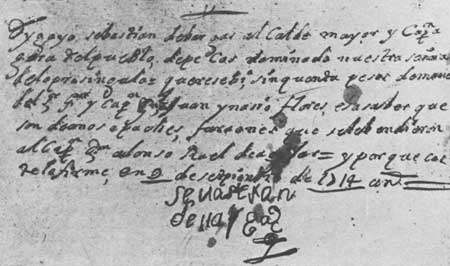

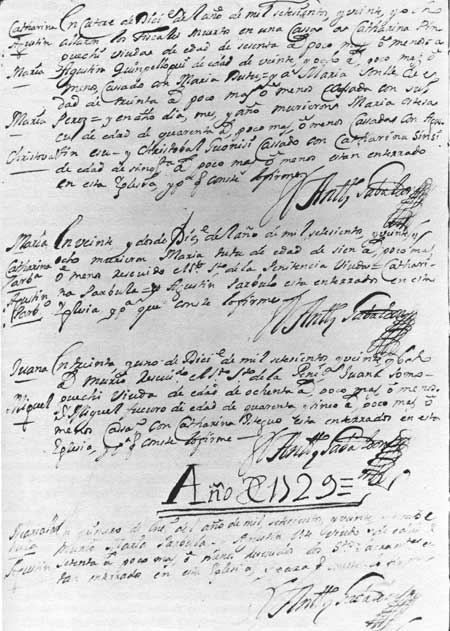

Vargas, in 1711 lieutenant alcalde mayor of Pecos and Galisteo, swore that he had seen the Pecos trading the awls to good advantage with heathen Apaches for buffalo or elk skins and meat. "He also saw how some of said Pecos Indians were taking to the Apaches a bowl-shaped basket of tobacco and with it an awl for which they got a skin." [7] When the Chipayne Apaches showed up at Pecos in August 1711 with their skins and captives to trade "as they customarily do some years," they sold out quickly and left. Later Capt. Juan García de la Riva discovered that he had bought not a heathen Plains Indian boy but rather a Spanish-speaking Christian lad abducted from the Rio Grande missions of Coahuila. Ordering everyone else who had acquired a captive from the Chipaynes to bring him or her in for examination, Peñuela identified three more Christians. He warned their new owners to treat them as such, then wrote to the governor of Coahuila via the governor of Nueva Vizcaya and the corregidor of Zacatecas asking what he should do. The response, if any, has not come to light. [8] It was customary in New Mexico for the alcalde mayor of the district to open and preside over the trading. As unobtrusively as possible, he was to set fair prices and to maintain order. All parties presumably benefited from such supervision and the heathens were spared "the excesses and injuries that arise from the insatiable greed of the citizens of this kingdom." Often Indians who had come in peace to trade had been provoked to anger by the Hispanos' misdeeds. The trouble was that hardly anyone could agree on the line between beneficial regulation of trade and monopolistic exploitation by the governor and his alcaldes mayores. The citizens were always complaining of interference by the alcaldes. In 1725, Gov. Juan Domingo de Bustamante, later accused by the friars of lining his pockets in every conceivable way, decreed for the record that no alcalde obstruct or alter the customary free trade in captives brought by the heathens to the Taos Valley, San Juan, and Pecos. He dispatched the original to each of the three alcaldes in turn for his acknowledgement and signature. As was standard, each official made a copy and posted it on the door of the local casas reales. Alcalde mayor Manuel Tenorio de Alba tacked up the decree at Pecos on October 1. [9]

Trade in Captive Indians

Although in volume and worth the trade in buffalo hides and fine tanned skins far exceeded the "ransom" of non-Christian captives, no item was more important to the local Hispanos or more avidly sought after than these human piezas. Mostly they were children or young women, for their men died fighting, were put to death, or were too tough to "domesticate." No Hispano of New Mexico, however lowly his station, felt that he had made good until he had one or more of these children to train as servants in his home and to give his name. Men wanted to present them to their brides as wedding gifts. They were as sure a symbol of status as a fine horse. Baptized and raised in Hispano homes, these captive Apache, Navajo, Ute, Comanche, Wichita, or Pawnee children assumed the culture of their new surroundings and lost their tribal identity, or, as the anthropologists say, they were acculturated and detribalized. When they came of age, they generally married others of their kind or, in some cases, a Hispano or a Pueblo Indian, further blurring their heritage. As a class in New Mexico they were called gen&icute;zaros. When captive children were acquired by the Pueblo Indians, they were of course baptized and given a Christian name to satisfy the friars, but they remained Indians so long as they kept to an Indian environment. Nor did they seem to lose their old identity so fast, at least not for a generation or so. It was the same with foreign Pueblos, who turned up in the Pecos books as Miguel Zia, Lorenzo Picuri, Antonio el Queres, or Antonio Tano; hence, Catalina la Yuta, Juan Antonio Jicarilla, and Juana Manuela Jumana. Although the exclusiveness of Pueblo society naturally limited the practice of keeping captives among them, some Pueblos did. On December 28, 1743, for example, after Fray Agustín Antonio de Iniesta had baptized two Apache girls at Pecos, he noted that "both of them belong to Antonio, the governor of this pueblo, who stood as godfather" Coronado had found slaves from the plains living at Pecos. Along with trade contacts, "under the eaves" of their pueblo and out on the plains, the presence of these foreigners among them may have "contaminated" the typical Pueblo communism with Plains individualism and self-assertiveness, at least among members of the more susceptible trading faction. Whatever the effect, it must have continued throughout the eighteenth century, for the missionaries assigned to Pecos kept baptizing, marrying, and burying a potpourri of Utes, Pawnees, Wichitas, unspecified Apaches, Jicarilla Apaches, Carlana Apaches, and a good many others identified simply as the children of "heathen parents." [10] For the Franciscans of New Mexico, the traffic in heathen children presented both an opportunity and a dilemma. The superiors vacillated. In 1700, the custos forbade the friars to acquire the ransomed offspring of Apaches or other heathens, even for the sake of making Christians of them or training them to serve in the convento. It laid the missionaries open to charges of acquisitiveness, trading, and keeping human chattel. The prohibition was reiterated often enough to indicate that the practice continued. In 1738, Custos Juan García did so once more: "Again we direct that the religious abstain from attending the trading, much less from acquiring piezas to sell and going armed for this purpose." [11] Yet, in 1749, Custos Andrés Varo conceded that they still did so.

Rowdy Traders at Pecos, 1726 A ruckus at the Pecos "fair" early in August, 1726, illustrates how fights could break out between an officious alcalde mayor and greedy traders. To hear Alcalde mayor Manuel Tenorio tell it, he was simply doing his duty, opening trade between the heathens and the many Hispanos who had collected that day and setting prices "favorable to the citizenry as is customary." But this time, a rowdy bunch of traders led by twenty-three-year-old Diego Manuel Baca of Santa Fe cut him short. Scandalously ignoring Tenorio and the office he held, they set up shop on their own and "in their ambitious greed" commenced trading straight-away. Seeing their hostile mood and how many of them there were, the alcalde judiciously with drew and looked for witnesses who would testify to this outrage. Coincidentally, don Pedro de Rivera, appointed by the viceroy to conduct an exhaustive inspection of northern frontier defenses, was still in Santa Fe. A Spanish-born member of his party had commissioned Alcalde mayor Tenorio to get him a good heathen child during the trading at Pecos. The Pecos missionary, Fray Antonio Gabaldón, also wanted a pieza pequeña. When the heathens arrived laden with buffalo meat to trade to the Pecos but with only a few captives, Tenorio's attempt to select the best two for his customers before opening the trading to anyone else evidently set off the row. Baca incited the others, yelling that the trading was for the people not for government officials. Pushing and shoving, they bid the four or five captives up to three and four horses each, plus bridles, "getting the worse of the bargain." It served them right, said Tenorio, who recorded the testimonies of four witnesses in his faltering hand and sent them off to Governor Bustamante. [13] Meantime, the aggrieved citizenry had prevailed upon certain of the friars to lay bare before Inspector Rivera the avaricious, stifling, illegal trade practices employed by Bustamante and his alcaldes to squeeze the New Mexico turnip dry. When the governor found out, according to one friar, his pleasant toleration of the Franciscans turned to mortal hatred. [14] Among the humble exports packed south by New Mexico's "merchants," buffalo hides and bales of tanned skins acquired in trade at Pecos and elsewhere ranked high. Up through the 1730s and 1740s, the era of Procurador general fray Juan Miguel Menchero, the Franciscans still freighted mission supplies north in wagons leased from private contractors, and merchants, both importers and exporters, still shipped their goods by agreement with the friars. Some New Mexicans made annual trips to the government-run stores in Chihuahua. Apparently certain of the friars were tempted too. In a report to Menchero, one conscientious missionary suggested that "the religious not be permitted to leave New Mexico for the villa of Chihuahua with the citizenry or for any other reason because this is usually [an excuse] to trade in tanned skins, buffalo hides, and other goods, all of which is foreign to the religious state." [15]

Later in the century, the great annual exodus to Chihuahua, the cordón or conducta as it was called, a raucous party of four or five hundred New Mexico traders and stockgrowers, with mule trains, soldier escort, and countless sheep, still carried the hides and skins from the plains. By then, however, Taos had far outstripped Pecos in volume. The reasons were several, the same ones that account for the pueblo's steadily declining population. Certainly the most dramatic was the appearance of a hard-riding, hard-fighting Plains people who began to war with the Pecos in the 1730s and who favored Taos for trade. Not that this people killed so many Pecos—a misconception invented by Governor Vélez Cachupín in 1750—but rather that they so turned the southern plains world upside-down that the Apache trading partners of the Pecos, their suppliers, were scattered about like chaff in the wind. This people was the Comanche. The Rise of the Comanche Nation The Comanche did not spring at full gallop from the head of a mythological buffalo. Their advent was almost meek. Drawn out of the basin and range country west of the Rockies by trade, horses, and the plains, they arrived in New Mexico about the turn of the eighteenth century in the tow of the Utes, fellow Shoshonean speakers. Almost immediately, allied bands of Utes and Comanches began contending with the semi-sedentary Jicarillas for hunting and trading grounds. By the second decade of the century, they had these Apaches begging the Spaniards for baptism. Their horse stealing under guise of peace, their murderous raids on the northern settlements, and their interruption of Apache trade had the Spaniards cursing their "barbarity." In 1719, Governor Valverde resolved to teach them a lesson. Mustered at Taos in September, this was no token force—sixty presidials, forty-five settlers, and 465 Pueblos, later joined by nearly two hundred Apaches. This was war. Fray Juan George del Pino of Pecos rode as chaplain. Strung out, Spaniards in front, pack animals in the middle, and native auxiliaries at the rear, with scouts ranging the flanks, they advanced northeastward through the pleasant valleys of Jicarilla and Carlana Apaches who pointed to the ravages committed by the enemy. Near the Arkansas River, they came on several deserted Comanche camps marked by cold fires and the tracks of travois poles leading away. The Cuartelejo Apaches clamored for Spanish aid, against Utes and Comanches, against Pawnees and Jumanos, against westward-moving Frenchmen who gave firearms to their enemies. But winter was coming. Valverde could not go on. He had not even seen a Comanche. [16]

By the time of Brigadier Pedro de Rivera's visit in 1726, the Comanches, "a nation as barbarous as it is warlike," had earned a notoriety of their own.

Displaced Apaches If the Pecos felt any pressure from the Comanches during the 1720s, the Spaniards did not record it. There is not even a reference to Comanches trading at Pecos. By the mid-1730s, however, the disruption these new plainsmen were causing had begun to strain the symbiotic trade relationships the Pecos had long enjoyed with certain Apache bands. Over the years to come, the quiet dissolution of this trade probably figured more heavily in the decline of Pecos than all the notorious Comanche assaults put together. [18] For the first time, displaced Jicarillas, formerly the special allies of rival Taos, began to appear in the Pecos books. Something was certainly going on during January 1734 when Fray Antonio Gabaldón catechized, baptized, and buried in the Pecos cemetery five Apaches. One he said was "a captain of the Apaches." Three were Jicarillas: a woman about ninety who had suffered an arrow wound in the heart, a boy, and a little girl. The following month he baptized another Jicarilla child "of heathen parents." These refugees, running from Comanches or other Apaches, had sought shelter at Pecos. In 1738, Fray Juan George del Pino, assured by the interpreter and the Pecos catechists of a Jicarilla woman's constancy and "moved by charity and the fear of her ill health, administered to her the water of baptism in the manner and form prescribed by the manual for adults." She had been living at Pecos for three years. [19] Comanche Assaults But it was the assaults that made news. Even though the first two Pecos deaths attributed to Comanches occurred in 1739, the really newsworthy attacks began in the 1740s during the governorship of Joaquín Codallos y Rabal. Why the Comanches, or one division of them, wanted to destroy Pecos and Galisteo is not clear. Certainly the Pecos had long been associated in trade with Apaches, and now they harbored Jicarillas. Whatever the reasons for the Comanches' grudge, they came not merely to steal horses but to vanquish as well. Few details of the first blow survive. It fell on San Juan's Day eve, June 23, 1746. The Comanches fought as if possessed. With a burning log, they tried to fire church and convento. The Pecos beat them back putting up so stiff a defense that the attackers finally withdrew after killing a dozen inhabitants, including two women, three children, and three Jicarilla Apaches. They abduced a Pecos boy seven years old, and they took off with the pueblo's horses. Reacting with unusual speed Lt. Gov. Manuel Sáenz de Garvisu, with fifty presidial soldiers, some civilians, and Indians from Pecos and Galisteo, gave chase. They found the boy dead on the trail "from arrows and hatchet blows." As they began to close, the Comanches, slowed by the stolen horses, wheeled around "in a great multitude" to do pitched battle. More than sixty of the enemy died according to Spanish count. But of far greater concern to the governor, nine soldiers and one civilian were killed. In brash defiance, Comanches hit Galisteo two weeks later killing an old man who was herding some cows. Reporting to the viceroy, Governor Codallos told how the Comanches were guided by apostates from New Mexico who knew the waterholes, ranches, and settlements. Besides that, they were a numerous nation and so well disciplined in warfare that they had defeated other Plains tribes and taken their lands. Codallos wanted greater authority so that he could carry "open and formal war" to the Comanches' own country. Following normal procedure, the viceroy requested an opinion of the Marqués de Altamira, his chief military advisor. What riled Altamira was the loss of ten Spaniards without "more punishment to the enemy than killing about sixty of them." As a result, the Comanches were "elated, vainglorious, and proud," as their subsequent attack on Galisteo demonstrated. Emboldened by a succession of victories over other Indians, and now by this affront to Spanish arms, these Comanches were obviously taking the offensive. They were jubilant over killing one Spanish soldier, Altamira opined, even at the loss of a hundred of their own, "which because of their barbarousness and their numbers is of small consequence to them." In sum, the governor, utilizing Comanche prisoners and the good offices of the missionaries, should offer the barbarians peace. If they refused, he should "banish them from that entire area." [20]

A Battle at Pecos, 1748 Although he won a satisfying victory in 1747, the overall effectiveness of Governor Codallos' Comanche policy can be judged by what took place at Pecos on Sunday, January 21, 1748. The afternoon before, near sundown, a messenger, whose face betrayed anxiety, delivered a note at the governor's palace. Snow lay on the ground. The air was brittle cold. Codallos read the note. It was from Fray José Urquijo of Pecos. A large force of Comanches had massed at the Paraje del Palo Flechado, only two and a half leagues from the pueblo. Urquijo feared an attack. Codallos showed the note to Fray Juan Miguel Menchero, outspoken special agent of the Franciscan commissary general. Menchero had recently coordinated a large-scale Gila Apache campaign—a role unbecoming a friar, some of his brethren said. Menchero cursed the luck. He was sick. He would have to send his secretary Fray Lorenzo Antonio Estremera. Codallos ordered the drum beaten. It was getting dark. Most everyone was inside by a fire. "In a villa, the capital of a kingdom, where there are more than 950 Spaniards and mixed-bloods and more than 550 Indians," according to one report, "only 25 persons, counting citizens and soldiers, assembled." Ten of them he dispatched for horses seven leagues away. With the other fifteen and Father Estremera, he mounted up and headed for Pecos. It was hard going, Estremera recalled, "the night black, the road bad, and the snow deep." But they made it, about two in the morning.

Heroics of Governor Codallos No one was asleep. The Pecos and their missionary were distraught, say the reports, all of which made Governor Codallos the man of the hour. Ascertaining first the direction from which the enemy was coming and roughly how many there were, more than 130, all mounted, he began giving orders. The Pecos assured him that Comanches did not attack at night. They had until daybreak. He told the pueblo officials to get the women, children, and old men up on the roof tops and bar all doors. A dozen of the old men waited in the convento to protect the missionary. The young men, the mocetones, armed with bow and arrows, shield, lance, and war club, rallied around him. There were about seventy, among them some heathen Jicarillas "of those who live in peace in the shelter of this pueblo." Through an interpreter, the governor explained his plan. Since all the pueblo's horses were out to winter pasture and those of the governor's men spent, they would have to go out against the Comanches on foot. It was absolutely necessary, he told them, that everyone stay together. They must not scatter. The rest of the night, while scouts kept watch around the pueblo, they remained under arms.

About eight o'clock, the Spanish-speaking Pecos stationed in one of the church towers shouted that the Comanches were coming up on the convento side, many more than a hundred, all on good horses. It was time. Swiftly they followed the governor through the gateway, soldiers, civilians, Indians, and Father Estremera, who had seen to their Christian preparation "with acts of contrition and general absolution for all exigencies." Taking up a position a short distance beyond the convento, everyone well together, they obeyed Codallos' order not to fire until the enemy committed himself, and then only on command. The Comanches advanced "with such an outcry and screaming to strike fear that only the presence of mind and energy of Gov. Joaquín Codallos, aided by God, could have overcome such boldness." When they were no more than a pistol shot away, the governor moved his men forward in order and the battle was joined. The Spanish "square" held. Firing several volleys point blank, using their lances and bow-men to good advantage, the governor's force repelled the cavalry assault, inflicting a goodly number of casualties. Startled, the Comanches withdrew a short distance "skirmishing with great agility." Most of them wore cueras, the protective leather coats, and carried a large shield, lance, bow and arrows, and some a sword or war club. During the lull, they picked up their dead and wounded, placing them across their horses. Meanwhile, eager to see what was going on, the old men Codallos had left in the convento told Father Urquijo that they would be right back. Slipping out and heading for a good vantage, they were spotted by one of two additional Comanche parties coming up to join the others. It was no contest. The Comanches ran them down. Eleven died. In addition, said Father Estremera, a Jicarilla had been killed in the battle, one civilian wounded, and a soldier's horse slain. The other two columns of Comanches rode in defiance by the governor a musketshot away and took their places with the rest. Now there were three hundred more or less. Promptly Codallos ordered his force to fall back on the convento little by little, the Indians first. The enemy watched. Just then on the road from Santa Fe, they saw the troops and extra horses coming to reinforce the governor. From a distance, the column seemed larger than it was. The Comanches withdrew to a hill a quarter-league from the pueblo. The men and horses from Santa Fe joined the others in convento and pueblo. A short while later, the enemy departed the same way they had come. "Thus it was assured," Father Estremera exulted,

That same afternoon Father Urquijo buried in the church the bodies of thirteen men who had died in the battle. The funeral rite was held next day. For the consolation of the Pecos, Codallos left a squad of soldiers. Six weeks later, when he wrote to the viceroy, he enclosed Father Estremera's sworn account of the battle at Pecos, so that his most excellent lordship, if he deemed it meet and proper, might commend the governor of New Mexico to the king. [21] | ||||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||||