Contents Foreword Preface The Invaders 1540-1542 The New Mexico: Preliminaries to Conquest 1542-1595 Oñate's Disenchantment 1595-1617 The "Christianization" of Pecos 1617-1659 The Shadow of the Inquisition 1659-1680 Their Own Worst Enemies 1680-1704 Pecos and the Friars 1704-1794 Pecos, the Plains, and the Provincias Internas 1704-1794 Toward Extinction 1794-1840 Epilogue Abbreviations Notes Bibliography |

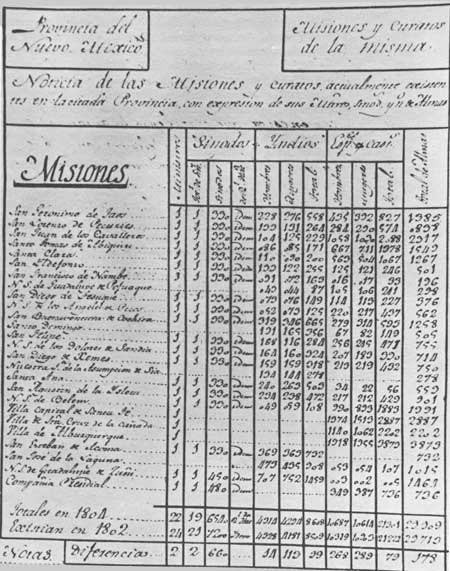

Governor Chacó Damns the Friars On the last day of 1804, Governor Chacón filed a state-of-the-missions report. It stung worse than the knotted cords of the disciplinas, the scourge. According to him, the missionaries were gouging the poor citizenry who depended on them alone for the sacraments. They charged exorbitant fees, disregarding the schedules set by the distant bishops of Durango. If someone could not pay a baptismal or marriage fee, the friars set them to work. It was common on the death of a poor colonist, said Chacón, that the friar suddenly became the deceased's sole heir, while the legitimate heirs found themselves reduced to utter penury. If anyone thought the Franciscans confined their venal practices to Hispanos, the stiff-necked Chacón meant to set him straight. The Indians had to pay to celebrate their mission's patronal feast, or else it was cancelled. It was customary, too, every All Souls Day, November 2, after the harvests were in, for the Indians of all the pueblos to enter the churches laden with offerings of produce of every kind. These went to the friars. When an Indian died, his family paid the missionary for the funeral Mass in livestock if possible, or, despite the natives' legal exemption, in personal service, "especially the friar who treated them well." For years, Chacón alleged, some ministers had let the Indians sell off portions of the four leagues of land each pueblo enjoyed under the law, thus contributing further to their charges' privation.

Addressing himself to the Franciscans' spiritual care of the Pueblos, the governor dragged out all the old allegations. Few of the Indians confessed annually, waiting instead until moribund, when they did so only through an interpreter. None of the missionaries in 1804 had a knowledge of the native languages, "nor," claimed the governor, "do they exert the least effort or application to acquire it." For the most part, the Pueblos understood Spanish but preferred not to use it, especially the women. The friars left religious instruction to other Indians, the fiscales—a scandal in Chacón's book.

A Church for El Vado Father Bragado endured at Pecos almost six years. He saw the rowdy mixed-breed communities of San Miguel and San José del Vado almost double in size. Evidently work was progressing on the San Miguel church, but not without incident. Once in the summer of 1805 when Manuel Baca, interim deputy justice of the district, ordered Ignacio Durán, in charge at San José, to beat the drum for the people to come work on the church, not everyone assembled. Reyes Vigil and his sons refused. When Duran ordered them, Vigil told him that he could "eat shit, eat a bucket of shit!" Afterwards, at Vigil's corral, the two got into a name-calling, rock-throwing, hair-pulling brawl. Because only a part of the record survives, the outcome of the ensuing legal action is not known. [11]

As their priest, Bragado found himself very much involved in the lives of the El Vado settlers. Early in 1809, he and Teniente de justicia Manuel Baca appeared together before Custos José Benito Pereyro to forgive each other and to drop the proceedings they had entered into. They vowed not to rekindle this or past differences. When the custos informed Gov. José Manrique of the reconciliation, the governor warned that it was not genuine. All Baca wanted was to bring to his side the woman who had been the cause of the trouble. Father Bragado had better watch his step. [12] Whether or not the Baca affair hastened his departure, Bragado cleared out early in 1810, the moment a replacement was available. The custos transferred him to San Ildefonso and assigned in his place Fray Juan Bruno González, an untried Spaniard who had arrived in Santa Fe on February 26 and who found himself minister of Pecos and El Vado on March 12. Like his predecessors, he soon learned that the settlers were as unreliable as the Pecos when it came to notifying the Father that someone was dying. He stayed not quite one year. [13]

Rebellion in New Spain As Fray Juan Bruno ministered on the Río Pecos, he heard the ghastly news of 1810. Unless inured by the incredible plague of events that had rendered his homeland a satellite of the monster Napoleon, the Spanish Franciscan must have blanched. A mad diocesan priest drunk with the heady spirits of the French Revolution, one Miguel Hidalgo, had raised the cry of independence and liberty at a little town northwest of Mexico City. The rabble had risen. They killed and burned and looted in an orgiastic caste war that threatened briefly to envelope the entire heartland of New Spain. But because the rebels were ill organized and unsustained, royal forces had taken the offensive. Before Father González left Pecos, they had captured Hidalgo. He was to be shot.

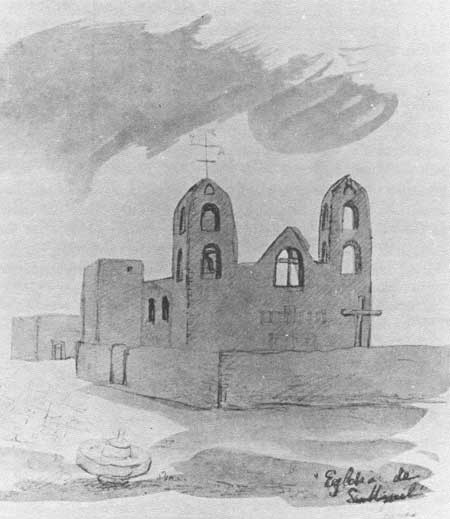

The Priest Moves to El Vado Twenty-seven-year-old Fray Manuel Antonio García del Valle, a native of Mexico City, did not stand on tradition. Granted, he had been appointed minister of the mission of Pecos, and it was still the cabecera, or seat of the "parish," but he saw no earthly reason for him to reside in a dying Indian pueblo when the large majority of his parishioners lived ten leagues or so downriver. After relieving González in March 1811, he baptized thirty-two infants for the settlers of El Vado before a Pecos Indian couple finally had a baby. That year the settlers at last finished the chapel of San Miguel del Vado. [14] Why should he not reside there?

To make his change of residence legitimate, Father García del Valle needed the approval of the see of Durango. The people of El Vado must send a petition. It was first-rate, a real propaganda piece. They chose José Cristóbal Guerrero, a genízaro of Comanche origin, to represent San Miguel and San José, two hundred and thirty heads of family "well instructed in the obligations of Christians." They made the most of the fact that Comanches, not really that many according to the books, were joining their communities and taking instruction for baptism. Not only did this swell their numbers, but it also cemented the peace between Comanches and Spaniards. "As a result," they predicted with chamber-of-commerce élan, "it is to be expected that within a few years these will be the most populous settlements in the province of New Mexico."

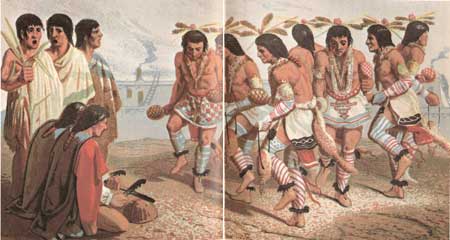

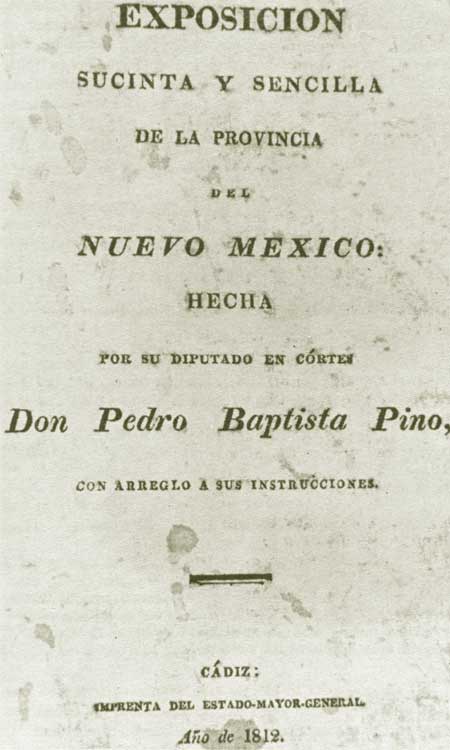

In sharp contrast stood the dying mission of Pecos. Only thirty families of Indians lived there "and of so little capacity that they received only the sacraments of baptism and matrimony." Fray Manuel, missionary at Pecos, had indicated to the settlers his willingness to move to El Vado. They requested therefore that he be allowed to do so, with the obligation of visiting Pecos with an escort once a month. Early in 1812, the diocese approved. For better or for worse, the Pecos had lost their resident minister for good. [15] Pino and the Spanish Constitution That same year in far-off Cádiz, capital of the resistance in French-occupied Spain, don Pedro Bautista Pino published for the benefit of his fellow delegates to the Cortés and the world at large an Exposición sucinta y sencilla de la provincia del Nuevo México. His goal was reform. Hoping to win for New Mexico the often-proposed diocese, he proclaimed the sorry state of the church in his province. All of New Mexico, with twenty-six Indian pueblos and one hundred and two Spanish communities, had only two secular priests and twenty-two Franciscans. Distances were great. As a consequence, many New Mexicans did without spiritual care. The absence of a bishop, moreover, had caused them, in Pino's words, to suffer "infinite harm." Not since 1760 had their primado pastor visited New Mexico. For half a century no one had been confirmed. They had forgotten that there was a bishop. Ecclesiastical discipline foundered. Many who needed a dispensation to marry, but who were too poor to travel to Durango to obtain one, lived and raised families in sin. It was a crime that a province producing nine to ten thousand pesos annually in tithes had not seen the face of its bishop in more than fifty years. "I, who am older," Pino confessed, "never knew how bishops dressed until I came to Cádiz." [16] He was convincing. The Cortés voted in favor of a diocese and a seminary college for New Mexico. On the Río Pecos a skeptical Father García del Valle took part in the excitement as the El Vado settlers elected their "parochial elector" under the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812, a thoroughly new experience. [17] But none of it came to anything. Napoleon let Ferdinand VII go. Once home on the Spanish throne, the king abolished the constitution, dissolved the Cortés, and nullified all its legislation. And that was that. As the people said, "Don Pedro Pino fue, don Pedro Pino vino." Enduring Comanche Peace For the most part the Comanches kept the peace. By the 1790s, it was habit. Even though the pueblo of Pecos declined visibly, even though more and more "comancheros" were taking the commerce of New Mexico out onto the plains, still the Comanches honored the tradition begun at the peace conference of 1786. They came to Pecos to trade, and they came to parley. When Tampisimanpe, the Eastern Comanche captain, reined up at Pecos in July 1797, he wanted to trade and parley. He wanted to see Governor Chacón confirm a "general" of the Comanche nation. It had been prearranged. The other Comanche captains had gathered. Next day at a solemn junta presided over by the Spanish governor, Canagüaip of the Cuchanticas received "a plurality of votes," whereupon Chacón recognized him in the king's name.

Before they departed, the Comanches presented to the governor two Spaniards, servants of a French trader abducted on the plains by unfriendly heathens. The governor sent them off to Chihuahua to see the commandant general. [18]

On occasion, Comanche leaders tried to put one over on the Spaniards. Chacón caught the Yamparika captain Guanicoruco at it in 1804. This Indian had traveled to Chihuahua, probably in the annual trade caravan, for an interview with Commandant General Nemesio Salcedo. He had several things on his mind. First, he was unhappy with interpreter Juan Cristóbal who neglected to carry the reports of the Comanches to Governor Chacón. He asked permission for a son of his, one José María who had received baptism at Chihuahua in 1803, to live at San Miguel del Vado and serve as interpreter there and at Pecos during the trading. He also requested license to hold the trade fairs at Pecos because, en route through the mountains from that pueblo to Santa Fe, their animals suffered and Apaches killed their women and children who followed along behind. Guarnicoruco had another son whom he believed should be named captain of the Yamparikas. Lastly, he volunteered to guide Spaniards to the Cerro Amarillo, fifteen days east of Pecos and El Vado, so that they could determine whether it was gold or some other metal. Salcedo, requesting that the governor keep him informed, passed these maters on for Chacón's attention. [19]

The New Mexico governor was frank. Guanicoruco was a liar. Interpreter Juan Cristóbal had not been assigned to the Yamparikas since Chacón took office. José María Gurulé was not a son of Guarnicoruco, rather a Skidi Pawnee genízaro who had once been a captive of the Comanches. Chacón had sent him to El Vado as Comanche interpreter with the first settlers. But because of Gurulé's unruly conduct, cheating, and horse thieving, the governor had removed him "at the petition of the entire nation" and put paid interpreter Alejandro Martín in his place. As for Guarnicoruco's request to trade at Pecos, that was absurd. "I have not heard," wrote Governor Chacón,

If Chacón tried to elevate Guarnicoruco's son, who was only fourteen or fifteen years old, he would lose the confidence of the rest of the nation. If this Indian knew where to find the Cerro Amarillo, let him bring in some samples. When Guarnicoruco showed up in Santa Fe, the Spanish governor reproached him for misleading the commandant general. Perhaps, the Indian replied, the interpreter had misunderstood what he was trying to say. [20]

| ||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||